* By Catalina Covacevich

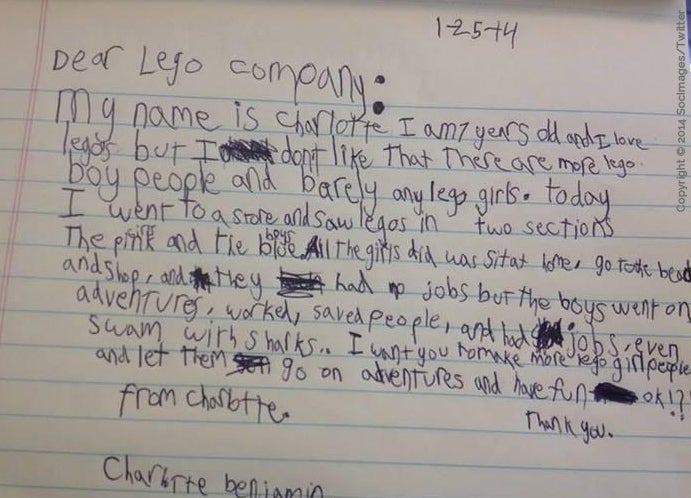

In January 2014, 7 year-old Charlotte Benjamin wrote to the Lego corporation, disappointed by the role of female characters in the company’s playsets. In her letter, she said that although she loves playing with Legos, she doesn’t like that there are more “Lego boys” than there are “Lego girls”. She also pointed out that “Lego girls” are always sitting in their houses without meaningful work, or going to the beach or on shopping trips. Meanwhile, “Lego boys” get to go on adventures, have interesting jobs, save people, and even swim with sharks! Charlotte wrapped up her letter with the following words: “make more ‘Lego girls’ and allow them to go on adventures and enjoy themselves, ok?”

Her parents published the letter on the web and it immediately went viral on social media. Surprisingly, Charlotte even accomplished that Lego launched a new line of three female scientists in response to her concerns.

Charlotte’s criticism applies to many situations in kids’ everyday lives. In addition to the people that surround children—like their families, schools, and friends—toys, books, advertising, television, and movies also reinforce stereotypes. All of society subtly, and at times even invisibly, participates in this social construction of gender!

Charlotte’s criticism is related to a problem that is very common in Latin American and the Caribbean: female participation in the labor force, at only 52.8%, is very low. This situation is difficult to reverse—even though today there are many more girls that attend school than 50 years ago. In spite of that, it seems that gender roles remain stereotyped —telling us that a man’s role is to provide for the family and the woman’s role is to stay at home tacking care of the children. In the education sector, we would hope that since school textbooks (which are the books with the widest dissemination) are tools created for learning, they would be free from stereotypes. But, how many girls and women appear in these texts? What roles do they assign to them?

Research on this topic has been undertaken in different countries since the 1970s. Their results signal themes similar to those identified by Charlotte in her letter. Along the same line, the recently published technical note “Gender inequality, the hidden curriculum in Chilean textbooks (only available in Spanish)” asks the following questions about textbooks in Chile: what gender contents do they transmit? how and in what way do men’s and women’s roles appear in the books? is a traditional view of gender relations conveyed or are alternative interpretations presented? In Chile, where the female labor participation continues to be even lower than the regional average, these questions are especially relevant.

Part of the findings confirm something that has been widely signaled by previous studies: the analyzed texts do not exhibit an equal treatment of female and male characters. There is a gendered division of work and, more importantly, greater protagonism and presence of male actors, demonstrating stereotyped gender roles. Males exemplify leadership, take risks, are self‑reliant and have ambition. Meanwhile, female characters are portrayed in caring and protective roles in the private sphere. Their emotional characteristics are emphasized and they are excluded from the political and scientific fields. Without a doubt, these tendencies also coexist with gender equality in subjects like social participation, recreation, space for social interaction, and the link between gender and nature when compared to other living beings. In addition, some roles (like analysts, athletes, or caretakers) are not stereotyped by gender.

Therefore, while we do see some advances compared with previous studies, many challenges to achieving an equal treatment of female and male characters in the analyzed textbooks prevail. In Charlotte’s words, although the Chilean girls and women do enjoy themselves like the boys and men, they still do not have the same jobs and get to take part in exciting adventures like their male counterparts do. It is important that we show more female scientists, doctors, writers, and politicians in these texts. We must portray them as protagonists and leaders, brave, and adventurous, whose attributes are not simply beauty and sweetness… On the contrary, what models are we providing to our boys and girls? How do we hope that our girls dream of entering the labor market and productively contribute to society beyond the realm of the family?

Leave a Reply