How do we know if childcare centers, preschools and home visits are effectively preparing children for school? How do we know if these services actually promote child development in young children? The question of how to measure access to quality services has been present in academia and policy for decades. So, where do we stand today and how should we move forward?

In general, the literature does not define what is meant by “access with quality”—that is a huge gap for policy making, multilaterals and governments. We know that information is needed on access, quality and participation in all types of Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE), ideally defined and measured similarly across countries. To achieve that, it is necessary to collect and analyze data on the characteristics of different programs and define the expectations of quality standards in each of them.

Why is this important? Accurate information on the quality of the ECCE is key to budget and programmatic decision-making. Having data and clear measures tells us the characteristics of the progress made in terms of service quality and potential impact on children and gives clues on how to continue to strengthen and improve interventions.

How should we move forward?

A recent article provides some clues, as it offers guidance on how to obtain better ECCE data and makes a call to action for the research community, governments and multilateral.

An important first step is to identify common ground among the indicators and measures under Target 4.2 of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which states that by 2030, “all girls and boys have access to quality early child development, care, and preprimary education so that they are ready for primary education.” In this spirit, the article refers to several measures of children’s development used in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) including Save the Children’s IDELA, the Global Scale for Early Development (GSED by WHO), and the East Asia–Pacific Child Development Scales.

Although “quality” is mentioned in the target’s language, no indicators were proposed for measuring the quality of non-home environments. This is due to the absence of a global definition of quality and the limited data on ECCE quality available from most countries. In this sense, it is key to highlight the importance of the concepts of process and structural quality, and identify several measurement tools, Environmental Ratings Scales; the Teacher Instructional Practices and Processes System (TIPPS); Measuring Early Learning Quality and Outcomes (MELQO); Teach Early Childhood Education (Teach ECE); and Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS).

An important source of information and expertise are the efforts made by LMICs in quality measurement and data collection, recognizing national-level initiatives in Latin America, such as the ones in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay; and in other latitudes such as Tanzania, Ethiopia, Egypt, and Liberia.

A call to action: Laying the groundwork for more comprehensive monitoring systems

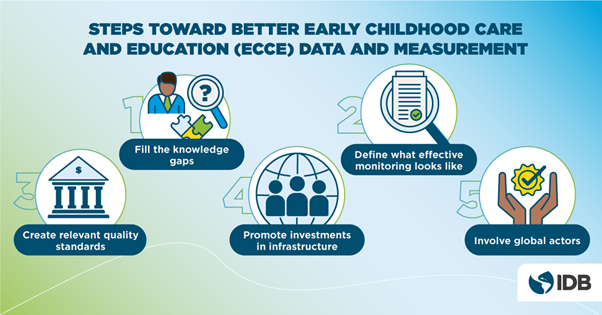

After a thorough analysis, the article proposes 5 concrete steps that can be taken toward better ECCE data and measurement with action items across communities of researchers, national stakeholders, and global organizations. These are:

- Fill the knowledge gaps: Researchers can help address gaps in knowledge by reviewing existing studies to clarify and document the types and characteristics of programs that promote young children’s development, especially in relation to dosage and participation.

- Define what effective monitoring looks like: Researchers can contribute to insight into effective monitoring systems, by generating new evidence and measurement tools, documenting approaches to implementing data and monitoring systems, and defining how these systems can help promote access to quality ECCE.

- Create relevant quality standards: Governments can create and implement scientifically informed quality standards that are culturally relevant, such as prioritizing aspects of learning environments that are culturally valued, and include all types of ECCE, private/public, and for all ages. Structural and process quality data can drive systems and program improvements.

- Promote investments in infrastructure: Investing in digital infrastructure for ongoing national monitoring of ECCE program quality is essential, by both national governments and international organizations. Depending on the status of country monitoring systems, this may require expanding the scope of these to include all types of ECCE, regular data collection on indicators of quality and the number and ages of children who attend, as well as investments in technology to facilitate data collection, aggregation, and analyses.

- Involve global actors: To leverage national and global momentum on measuring, global actors, such as UNESCO and UNICEF, can define and collect proxy indicators of access to quality ECCE.

Which of these steps do you consider most important? Which ones are being implemented in your ECD ecosystem? What challenges and opportunities have you identified regarding effective ECCE measurement? Please feel free to join this conversation by sharing your thoughts with the hashtag #ECDHubLAC and leave your comments below.

The authors of the academic article are Abbie Raikes, Nirmala Rao, Hirokazu Yoshikawa, Caroline Cohrssen, Jere Behrman, Claudia Cappa, Amanda Devercelli, Florencia Lopez Boo, Dana McCoy, and Linda Richter.To view full article click here: Global tracking of access and quality in early childhood care and education.

Leave a Reply