Experts often try to identify the “right” policies for enhancing development. Should public utility companies be in private or public hands? Are pay-as-you-go social security systems more sustainable than fully funded systems? Do industrial policies work? Do capital controls reduce external risks? But experience is a hard tutor. It teaches that the search for a universal set of correct policies or magical solutions is futile. What works at a particular moment in time in a given country may not work at a different time or in a different country. As time has passed, and Latin American and Caribbean nations have gyrated between state-controlled and market-centered policies, and between radically distinct trade and industrial policies, it has become glaringly evident that more important than the content of public policies are the characteristics of those policies, as determined by the policymaking process itself. In 2005, the IDB published a flagship report entitled the Politics of Policies, which attempted to shift the focus from technocratic policy prescriptions to a study of the key ingredients behind successful governance.

The report looked at the processes that shape credible policies. It examined what was necessary to implement those policies and sustain them over time, and it provided new indicators that allowed for cross-country comparisons to evaluate how the region’s nations were doing in specific policy arenas. Since then the IDB has published many specialized books on the budget process, social programs and other aspects of policymaking in the region that apply the framework of that seminal 2005 study. It also has watched with satisfaction as its approach has become an accepted framework for studying the region’s political economy. At the 20th anniversary of the establishment of the Research Department , the IDB looks back at those achievements with pride. Moreover, it continues to refine the original work, updating its approach and findings so that they increasingly bolster the IDB’s mission.

The Politics of Policies identified several key features of policies that determined their ability to enhance development over time. To be successful, it found, policies should be stable, so that they change in response to economic or other conditions, rather than shifts in the political winds. They should be adaptable, so they can be adjusted or replaced when needed; well coordinated among different agencies and levels of government; well implemented and enforced, and efficient. Finally, they should be “public-regarding,” promoting the general welfare, rather than rewarding specific individuals, factions or regions. Those characteristics, the evidence has shown, are absolutely critical. A so-called “best policy” that lacks credibility and fails to encourage long-term cooperation in the political sphere may be far less effective than a less-than-ideal, but stable and well implemented one. Indeed, a credible, though imperfect policy, can have great virtue. That is especially the case if it provides actors with the ability to adapt, invest and respond efficiently to it. Unfortunately, Latin America and the Caribbean lags behind other areas of the world in the quality of policy features that make for long-term, effective, policymaking processes.

In the most recent examination (Franco Chuaire and Scartascini, 2014), Latin America and the Caribbean scores only better than Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia in an overall policy index of seven regions, including high-income OECD countries, as shown in the picture.

Figure 1. Policy Index across Regions of the World

Source: Franco Chuaire and Scartascini (2014) A look at the individual components of the index hardly improves the picture. Latin America’s policies are third from the top in their public-regardedness, trailing only those of the OECD countries and the Middle East and North Africa because of high investment in social protection programs. But in the coordination index, the region again is third from last, marred by poor communication among ministries and levels of government. Its failure to compel compliance with rules and regulations helps place it third from last in the implementation and enforcement category. Rampant tax evasion is but one example. And it is similarly near the bottom in the efficiency of its policies, as evidenced by the minimal improvement in education, despite the large outlays in that area.

Table 1. Policy Features Ranking by Region

Source: Franco Chuaire and Scartascini (2014)

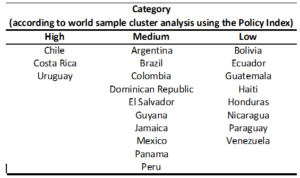

A few of the region’s countries stand out for their excellence: Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay perform alongside high-income developed countries in the overall policy index. But 10 Latin American and Caribbean countries are in the medium range, and another eight—Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Venezuela—are among the lowest achievers.

Table 2. Latin American Countries Ranking: Cluster Analysis Worldwide Sample

Note: Countries ordered alphabetically within each category.

Source: Franco Chuaire and Scartascini (2014)

Policy features do not exist in a vacuum, of course. They are endogenous, depending on the capabilities of government institutions, such as the institutionalization of Congress, the independence of the judiciary, the quality of the civil service, and the institutionalization of political parties. Those characteristics, as described in the 2014 update, will be reviewed in a subsequent blog. But a review of the index gives researchers and policymakers a start. Together with the data on government capabilities, the index provides reference points for what needs to be improved in areas such as policy design, implementation and enforcement as well as long-term cooperation among domestic political players so that political processes and policies might better serve the goals of equitable and sustainable development.

Leave a Reply