Among Latin American nations, Chile has achieved rare success in developing strong macroeconomic fundamentals, a transparent regulatory system, and improving in other indicators of economic and social wellbeing.

That should come as no surprise.

Chile has good policy features and strong government capabilities. Its congress consists largely of well-educated politicians with high levels of technical expertise, numerous years of legislative experience and professional staff. It has a capable, meritocratic civil service and a highly independent judiciary. Endowed with those institutions, and the consistent, technically competent policies that go with them, the nation has registered solid economic performance while advancing into the ranks of the world’s best policymakers.

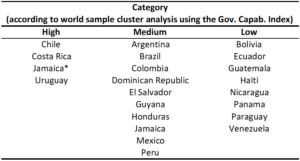

Table 1. Latin American Countries Ranking: Cluster Analysis Worldwide Sample, Government Capabilities

Source: Franco Chuaire and Scartascini (2014)

Note: Jamaica’s index has lower confidence than the rest of the countries because its construction lacks more than half of the components for two of the indices.

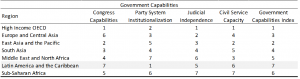

Sadly, however, Chile is a bit of an outlier in Latin America and the Caribbean. In the IDB’s most recent examination of government capabilities worldwide, (Franco Chuaire and Scartascini, 2014), only Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay ranked among the world’s top performers. But six countries, including Mexico and Brazil, placed in the medium range, and 11 countries, including Argentina, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela, ranked in the world’s lowest group. The region’s results as a whole were dismal. In a ranking among six geographic regions and the high income OECD countries, Latin America and the Caribbean was last in overall government capabilities, behind even Sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2005, the IDB published a flagship report entitled the Politics of Policies, which examined key ingredients behind good governance. The report looked at the characteristics of political institutions that allowed stable, adaptable, publicly-minded and efficient policies to be made and endure over time. Important among them, it found, was the existence of a small number of well-institutionalized political parties (or coalitions) with long-term political platforms and an ability to forge consensus. Also essential were a legislature with a strong policymaking capacity and an ability to stand up to a powerful executive; an independent judiciary, and a civil service able to enforce agreements and prevent special interests from benefiting at the public expense.

Table 2. Government Capabilities by Region

The government capabilities index, which measures the strength of those institutions and provides a composite score, provides the region with plenty of food for thought—and a clear cause for alarm. Higher government capabilities dramatically affect a nation’s prospects and are associated with higher rates of GDP per capita growth and improvements in the Human Development Index. They also correlate with less distortive tax systems, higher quality infrastructure and labor market flexibility. They allow governments to generate the conditions for higher financial development and advance more rapidly in social sector areas, including more effective health and education spending. By contrast, weak government institutions in Latin America and the Caribbean represent a drag on development. They inhibit the creation of credible, stable, adaptable, publicly-minded and efficient policies that can persist over time even with changes in the electoral composition of legislatures and the arrival of administrations with radically different agendas.

What can be done? Not all is gloom. The region traditionally has had a relatively high level of party system institutionalization, including many countries that enjoy parties with long traditions and solid bases of support (even if some of these bases of support have been built around clientelistic instead of programmatic agendas.) All these conditions can help provide policy stability over time. But in the other indexes of government strength—congressional capability, judicial independence and civil service capacity—where Latin America and the Caribbean ranked either last or among the bottom three, the room for improvement is vast. Too many countries in the region suffer from sub-standard congresses. Their legislators lack experience, expertise, and professional staff and, in many cases, seem uncommitted to investing in the capacities of the institution to which they belong. Too many nations are served by civil services where employment depends more on political patronage than merit or technical skills. With few exceptions, judicial independence is an oxymoron. In several countries the courts are losing even the little autonomy they once had.

The international community must help the region strengthen those institutions. It must help protect them from manipulation by the Executive of the day and work to increase their capacity and transparency. That doesn’t mean insisting on so-called “best legislation.” Ostensibly ideal civil service laws copied from other countries will prove meaningless in contexts where the political actors have every incentive to ignore them. Nor does it mean pouring in money for material infrastructure, like computers, that will have no effect as long as the institutions themselves are defective. Instead, it involves using expertise and financial influence to force governments to invite the opposition and as many other players as possible to the table in the interest of enduring institution building, accepting incremental progress and “safe bets,” and striving to create incentives that push political players to ignore short-term political temptations in favor of long-term consensus and cooperation.

Leave a Reply