![]()

House of Cards returned to Netflix this weekend, along with Kevin Spacey’s Machiavellian politico Frank Underwood, who now holds all the cards as president of the United States. House of Cards transports millions into Washington’s corridors of power, offering a glimpse into the backroom machinations of policymaking. Of course, as the show suggests, any similarities to real events are purely coincidental. Still, certain patterns hold true.

What triggered Frank Underwood’s thirst for revenge was that he wasn’t appointed Secretary of State, and his “vision of power” was checked only by his position as Congressman. Underwood puts his perverse abilities to work running Capitol Hill and basically driving all congressional decisions. In reality as in fiction, seniority and leadership positions matter, and positions on key committees are essential to wielding power and influence.

Would a Latin American-style House of Cards be able to replicate the same story line? Although it is difficult to generalize about the region as a whole due to the wide variance across countries, several publications by the Research Department, including The Politics of Policies, Policymaking in Latin America, How Democracy Works, and El juego político en América Latina, have revealed certain patterns.

Interestingly, despite the region’s tendency to have a very strong executive branch, where presidencies have been considered the root of all good and evil, the inner workings of the executive branch in Latin America remain largely unexplored (Bonvecchi and Scartascini, 2011). The president and the executive branch are usually treated as black boxes, even though the presidency has evolved into an extremely complex branch of government. One feature that characterizes the region, however, is that in many Latin American countries, cabinet positions have been used to build coalitions in otherwise fragmented contexts. (Unlike in the U.S., most Latin American countries have proportional-representation electoral systems, which increases the number of parties competing for office.) This feature has made most cabinet positions—other than the finance ministry—less relevant for policymaking. Moreover, cabinet stability has traditionally been very low; according to data compiled by Cecilia Martínez-Gallardo in How Democracy Works, the average tenure of ministers in the region was around 20 months.

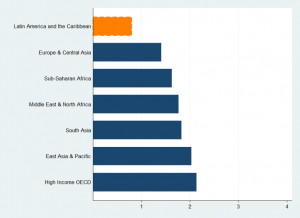

How does the role of Latin American legislatures work? We know plenty about that. As described in “The Weakest Link: Government Capabilities in Latin America and the Caribbean” and shown in the figure below, congressional capabilities in Latin America are low. In that respect, the Latin American region ranks at the bottom. Consequently, legislatures play a far less relevant role in Latin America than they do in the U.S.

CONGRESSIONAL CAPABILITIES BY REGION

Source: Franco and Scartascini (2013).

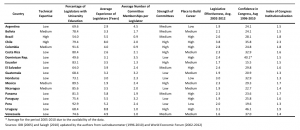

As the roles and features of the U.S. Congress play out in House of Cards and the components of congressional capabilities in Latin America are disaggregated (see the figure below), the differences between the two types of legislatures become even starker. For example, Latin American lawmakers tend to have relatively less expertise and much shorter careers than their U.S. counterparts. Unlike in the U.S., where some legislators can make a lifelong career in Congress (to wit Ted Kennedy and Strom Thurmond, for instance), legislative tenure in Latin America tends to be limited to a few years. One striking contrast between the two regions is the role played by congressional committees. Although these committees are extremely important in the U.S. and in House of Cards, they are usually irrelevant in Latin America. Another major difference concerns the choice of Congress as a place to build a career. While most politicians in the U.S. tend to establish their careers in Congress (e.g., like Frank Underwood, Barack Obama and Joe Biden both got their start in Congress), most politicians in Latin America would rather aim for the executive branch than build a career as a legislator first.

Source: Palanza et al (2012)

Thus, when watching House of Cards, it is important to remember that what transpires in the corridors of power in Latin American capitals may be equally entertaining, but it is another story indeed.

***

Leave a Reply