Caribbean countries have long been among the most indebted on earth, and related vulnerabilities have slowed growth and poverty reduction across the region. Our chapter in Economic Institutions for a Resilient Caribbean—entitled: Debt Management and Institutions in the Caribbean: Best Practices and Priorities for Reform—focuses on debt-related vulnerabilities affecting Caribbean countries that are members of the IDB’s Caribbean Country Department—The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

In it, we undertake a detailed review of factors that have driven debt accumulation, identify common factors that have driven debt and related economic crises, and also review the evolving consensus with respect to sound international practices for debt management. In this context, we discuss priority reforms with the potential to help address existing deficits, and insulate Caribbean economies from future shocks, in order to support faster and more inclusive growth.

Caribbean Countries: Among the World’s Most Indebted

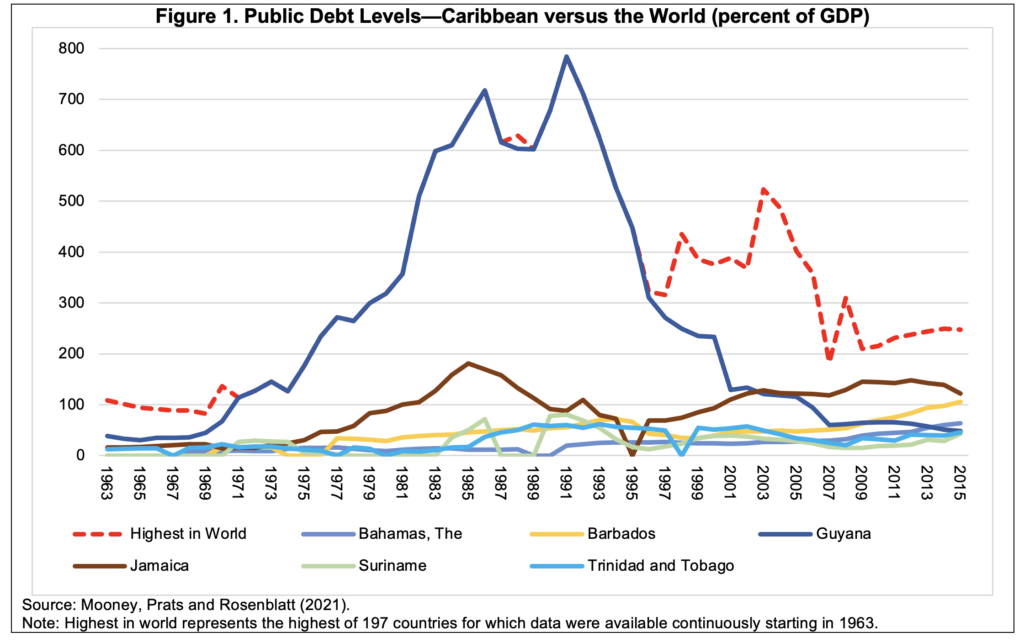

The history of public debt in Caribbean countries is striking. Several countries in the region have been among the most indebted in the world (measured in terms of the public-debt-to-GDP ratio) since gaining independence beginning in the 1960s (Figure 1). While economic and debt crises have been common throughout Latin America and the Caribbean over the past century—particularly when compared to other regions—the frequency, depth, and duration of such episodes for Caribbean countries makes it an outlier.

Debt vulnerabilities hinder growth…

This is particularly significant given the development needs of many Caribbean countries. High debt levels and weak institutions and capacity for public financial management have held back growth, incomes, and living standards for millions of people. Standard economy theory tells us that developing countries—where capital is scarce and labor is abundant—should borrow resources from abroad to support faster development. In this context, developing countries also tend to suffer from large and persistent public and social infrastructure deficits that act as brakes on private sector investment and productivity growth. Many of these deficits must be addressed with prudent public investment and expenditure, generally requiring governments to borrow both domestically and from abroad.

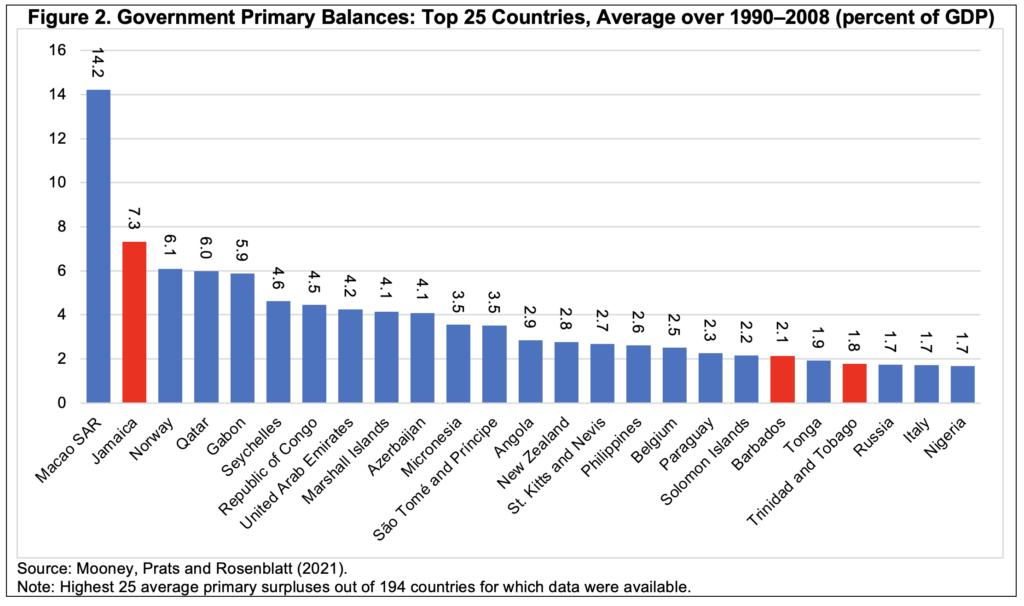

Given their history of recurring debt crises, Caribbean countries have undertaken numerous debt restructurings (though some have been characterized as voluntary in nature), and their governments have been forced to initiate some of the most severe fiscal adjustments ever contemplated in the context of emergency reform programs aimed at restoring debt sustainability and macroeconomic stability. For example, Jamaica recorded the highest average primary fiscal surplus in the world for a sovereign nation from 1990 to 2018 (7.3 percent of GDP), while other countries in the region, including Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago, also ranked near the top of the list globally on this measure over the same period (Figure 2). While this is only one measure, what is clear is that recurring crises have led to severe constraints with respect to fiscal space, acting as a break on critical investments in both infrastructure and social services, that developing Caribbean countries so badly require.

So why have Caribbean countries been so indebted and crisis prone?

There are many reasons for these outcomes. It is clear that initial conditions mattered for many of these countries, as the group includes some of the youngest nation-states in the hemisphere, and many were severely lacking in terms of financial and technical resources after gaining independence, amplifying existing vulnerabilities to economic and other shocks. Caribbean countries are small, open, and in most cases island economies, making them particularly dependent on external demand and capital flows, as well as susceptible to related shocks from abroad. Their small size and limited economies of scale have led to narrow production bases, and in some cases outsized sectors—for example, commodity exports or tourism—that further amplify vulnerabilities to swings in external demand. Similarly, their geography makes them among the most vulnerable on earth to weather-related shocks, as well as the implications of climate change.

In our chapter, we undertake detailed decompositions of debt dynamics for all six countries. Based on this analysis, we identify several common factors that have contributed to debt accumulation and related vulnerabilities across the Caribbean, including:

- Fiscal deficits are not all that matters. In some cases, countries hardest hit by debt crises had been running large fiscal surpluses during their most pronounced shocks to public debt, bending against the prevailing wisdom that deficits always drive crises.

- External risks from poor liability management. We find other factors, such as poor portfolio construction in terms of the currency and cost structure of debt, that left countries vulnerable to exchange rate shocks.

- Contingent liabilities were important drivers. Countries also suffered from large shocks to sustainability from the crystallization of contingent liabilities and/or other unanticipated debt-creating flows. Deficits “hidden” in state-owned enterprises were an important factor compromising debt sustainability.

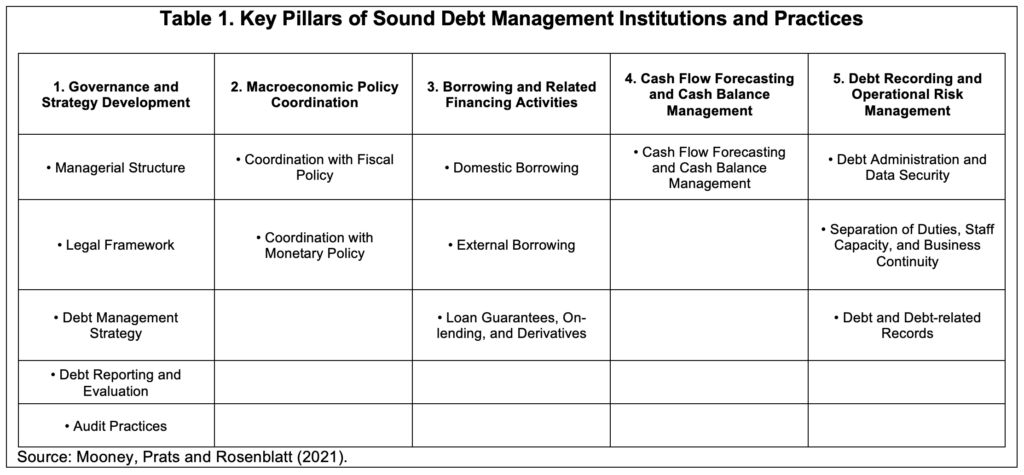

Taken together, these findings suggest that deficiencies in debt management institutions, practices, and capacity were important contributors to the region’s debt-related woes. In this context, our chapter provides a broad overview of international best practices related to debt management institutions, and discusses areas where Caribbean countries have scope for improvement, which can improve public financial management, and help to insulate our economies from future debt vulnerabilities. See Table 1 for a broad overview of sound institutions and practices in related areas.

While further diagnostics are warranted, our review of the history of debt accumulation in the Caribbean, the policy implications of these vulnerabilities, and common institutional deficits suggest that much remains to be done to bring Caribbean country practices and capacity up to the level of international sound practices. This will be a crucial undertaking for countries in the region, as they strive to establish and maintain macroeconomic stability, without which development aspirations are likely to remain unmet.

Leave a Reply