Infrastructure and accessibility: When public buildings are not for everyone

Laura is a 24-year-old woman who visits her local library daily to read for two hours. Even though she can enjoy the great collection of books and spaces, every day she must face barriers that remind her why the library is not a place for everyone.

The service staff does not have the tools to communicate with Laura. When schedule changes are announced on speakers, and Laura can´t find out about them with anticipation. Some days, lights go off and Laura gets scared when finding de way out becomes hard. Laura can´t access the seminars and talks organized by the library, nor can she tell when the loud emergency alarms go off and evacuation of the building is required.

Laura wishes she could enjoy all the services available in the library in an independent and safe way. She wishes to communicate, share, and have the same rights every other citizen has when accessing public spaces and services in her city. However, Laura is a deaf woman, and the library has no sign interpretation service. Every day, her context reminds her of her disability.

Having a disability in a city with barriers

Lack of accessibility to public infrastructure is what persons with disabilities –who represent 14,8% of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean– must face every day in our cities. Barriers found in health centers, schools, museums, government offices, and recreational facilities forbid citizens with disabilities to access basic services. Education, health, entertainment, and work not only depend on the quality of the service, but also on the accessibility of the infrastructure where these services are offered. That is why, without considering how to improve accessibility, we are decreasing social and economic opportunities for the population with disabilities.

A change of paradigm on disability

For decades, disabilities were understood from a medical paradigm as a biological condition or a sickness. However, thanks to the social model, nowadays we know it actually depends on the context that surrounds a person, and that a disability lies in the interaction between a person’s deficiencies and external barriers.

“A disability is the result of the interaction between a person and his environment”

United Nations Enable, 2007

Mapea lo accessible: a project for inclusion

In our region, we have a big challenge: the information on accessibility in cities´ public infrastructure is limited or inexistant. Sharing this information can reduce uncertainty on the characteristics of installations, which might be dissuading people with disabilities´ participation and use of services.

This is why, since 2020 the IDB has been working in “Mapea lo accessible” (Map what’s accessible). This initiative seeks to promote more inclusive and accessible cities, where people with disabilities have more autonomy, and where civil participation and technology become tools for accessibility.

Laura tells us she has tried to find information on accessibility in different libraries and public spaces in her city. However, she hasn´t succeeded. In a survey led by the IDB in cities that participate in this project, 64% of people with disabilities said they look for information on accessibility daily, but often cannot find it easily. Nowadays, information is power, and technology is a tool available to everyone to access this power.

How is the data generated?

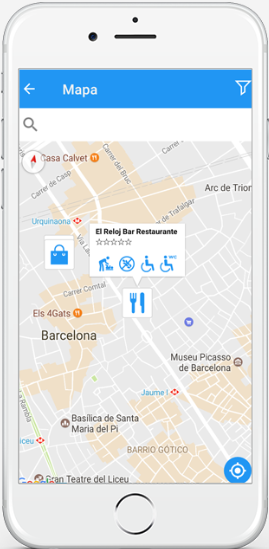

The answer is: in a collaborative way. Mapea lo Accesible is a call to action, and invites all citizens to “map” cities, indicating accessibility characteristics in every public building through mobile apps. For this first phase we are working with Mapp4All, an accessibility app that is free and available in 9 languages.

When we think about accessibility in infrastructure, normally, the first thing to come to mind is a ramp in an entry. As a consequence, current mapping technologies have focused mainly on physical accessibility measures. However, Mapea lo Accesible seeks to measure a list of objective indicators, relevant to other people with disabilities, which can be easily recollected in a collaborative way. Some examples are:

- Tactile guide to reception

- Texture and color signing before a set of stairs

- Sign language interpretation service

- Entrances at least >90 cm wide

A guide for better public policies

Information on public infrastructure accessibility can also allow policy makers to make plans based on updated information on accessibility gaps. In this line, Mapea lo Accessible aims to be an information tool for citizens, at the same time it adds value at a local and municipal level. This makes informed decision making in accessibility issues easier. Additionally, there is also an exchange of knowledge and good practices between cities participating in the project. Both fronts will allow the region to advance in initiatives that promote accessibility and inclusion, such as reasonable adjustments and innovating and cost-effective solutions.

These measures can be Braille signing in buildings and the possibility of communication assistance systems such as live audio digital transcription. It sounds complex, but it doesn´t have to be.

With COVID-19, for example, a lot of public spaces had to adapt to new biosecurity measures. Floors and walls in public infrastructure had to incorporate signing, such as colored lines, so people would know where to move and stand. These types of reasonable adjustments can also improve accessibility for people with a visual disability if we include texture and transform them into podotactile guides.

5 more accesible cities

Mapea lo Accessible will start with 5 cities from Latin America and the Caribbean:

- Guadalajara (Mexico)

- Tegucigalpa (Honduras)

- La Paz (Bolivia)

- Uberlandia (Brazil)

- Salvador de Jujuy (Argentina)

The goal is to replicate this initiative in many more cities withinour region. To achieve this, the project involves everyone: people with disabilities, their families, civil society, local government officials, the education sector, and the private sector.

We invite all citizens to follow the project, join the Mapea lo Accesible community and keep an eye on activities and mapping sessions in these cities in the following months. If you want to join the initiative, get in touch with the team at [email protected].

Leave a Reply