The gender gap in mathematics is closing in Latin America and the Caribbean. Girls are on par with boys in most participating countries in the most recent regional standardized test. Yet, they continue to be underrepresented in courses and careers in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics). Research often attributes the lack of women and girls in STEM to stereotypes and discrimination.

To change this reality, the Deciding My Future (Decidiendo Mi Futuro) program was developed in Costa Rica. Through text messaging, the initiative impacted the enrollment in STEM of girls from low-income households.

How big are biases against girls in STEM?

An IDB regional survey found that such fears of discrimination and biases about girls and women in STEM are indeed pervasive. Eight out of ten female youth think they would suffer discrimination if they pursued a career in STEM. And the survey found close to a 30-percentage point gender gap in the wish to pursue STEM careers.

The gap was even more elevated when looking at hard sciences, including exact sciences, IT, industry, mechanics, and technology. Only 3 to 4% of male and female youth thought it appropriate for women to work in hard sciences. But 50 to 60% think that men belong in these fields. Since hard sciences are precisely the careers for which the labor market pays the most, by opting out, women are tracked away from high-paying jobs. Information on the returns to STEM careers is also gendered. While 50% of male students reports knowing that STEM careers have higher returns, only 36% of their female peers do so.

These stereotypes are harmful because as girls internalize them, they grow up convinced that they don’t belong in STEM. No wonder, that when it’s time for them to make course selections for high school and college, they opt out of STEM.

Deciding My Future, Costa Rica’s initiative to achieve more girls in STEM

In the face of these blatant stereotypes among both male and female youth, getting girls to choose STEM careers may seem like a tall order for any education policy maker. Yet, in Costa Rica – one of the countries in the regional survey- the Ministry of Education (MEP) – – put aside feelings of defeat and decided to try a low-cost approach. In partnership with the IDB and IPA (Innovations for Poverty Action), they launched the Deciding My Future campaign to convince girls to select STEM high school courses.

Four types of text messages to reach out to girls

The Deciding My Future campaign reached out to female 9th graders and their families for twelve weeks, leading up to high school course selection. The contacts were made through four types of text messages. A first group of messages shared inspirational stories about women in STEM, such as the life of Hedy Lamarr, the inventor behind Bluetooth, secure Wi-Fi and GPS; Mariana Costa, who started a social enterprise to train young women to do web design; and Ada Lovelace, a mathematician who developed the foundations for programming language.

A second group of text messages advocated the benefits of pursuing STEM careers, explaining that technology careers present opportunities as many companies are looking for people with STEM skills. This group of messages provided information about STEM, both on its financial returns as its non-financial returns, such as the benefits that science brings to society and communities.

Since the regional survey had found that female youth were much less aware than their male peers of the higher returns in STEM-fields compared with other career paths, the aim was to close this knowledge gap.

Since fixed mindsets about women’s abilities in STEM have been linked to women’s underperformance in STEM, a third group of messages fostered mind growth. For example, reminding girls that: “No one is born knowing math, science or programming. Like any skill, with effort and time you will improve. You can do it if you put your mind to it!”

Finally, messages were sent with information on STEM careers that are available to students and the enrollment process.

The results: increased enrollment of girls from low-income households

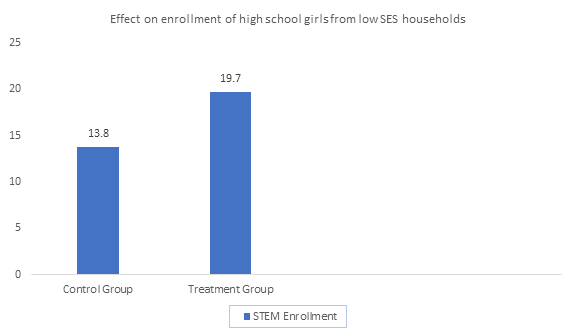

The campaign was evaluated through an experimental design where half of the 858 participating households received the messages. The other half served as a control group. The effects from the Deciding My Future campaign were largely concentrated in youth from low Socioeconomic (SES) households. This is the least represented group in STEM careers across the Latina America and the Caribbean. The enrollment of girls from low SES households increased on average, by 5.9 percentage points, which is a substantive reduction in the SES enrollment gap.

Another noteworthy effect was a 5.4 percentage point increase in enrollment among those who at baseline had reported downward misconceptions about the financial returns to STEM careers.

The participation of women and girls in STEM has resisted change. The findings from Deciding My Future inspires hope because of its simplicity: simple text messages leading up to high school course selection. Hope that it may be possible to foster sufficient sense of belonging and interest in STEM to boost female enrollment in these rewarding and fascinating fields.

Leave a Reply