By Arjun Chowdhury and Cesi Cruz

What links Latin American nations to failed states like Syria and the Democratic Republic of Congo? By most objective measures, not much. Syria is the epitome of chaos, suffering from a civil war that has killed hundreds of thousands and displaced or exiled millions more. Ethnic, religious and political conflict similarly takes a huge human toll in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Most of Latin America, by contrast, enjoys peace. In 2016, Colombia signed an agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) to end the region’s last civil conflict, and despite a few notable political conflicts, the region stands out for its democratic institutions. It is now, as we point out in a recent blog, the most electorally competitive and democratic in the developing world.

But that doesn’t mean that the region’s future is guaranteed. If it has come a long way since the military dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s, it is still riven in many places by endemic corruption and clientelism, insufficiently independent bureaucracies and judicial systems, and drug and gang violence. Those things, despite the progress, make most of the region’s countries weak states rather than well-functioning and sustainable ones like Britain, Canada or Germany.

States can weaken and tip into failure

In this, they are not alone. Weak states – those that are unable to deliver services and monopolize violence within their borders – are actually much more numerous worldwide than those that monopolize violence and consistently deliver services. Moreover, states can weaken over time and tip into failure. This can happen slowly – think of the decline of the Zairean state over three decades of Mobotu’s misrule – or go from relative stability to civil war in a matter of months – think Gaddafi’s Libya. What then are the factors that might potentially threaten Latin American governments’ capacity and make them vulnerable to failure?

To answer some of those questions, we turn to the brand new Database of Political Institutions (DPI 2017) hosted at the Inter-American Development Bank. DPI 2017 is a joint effort by Cesi Cruz, Phil Keefer, and Carlos Scartascini, and presents institutional and electoral data for 180 countries from 1975 to 2017. Variables include indicators of checks and balances, government stability, identification of party affiliation and ideology, and the composition of legislatures.

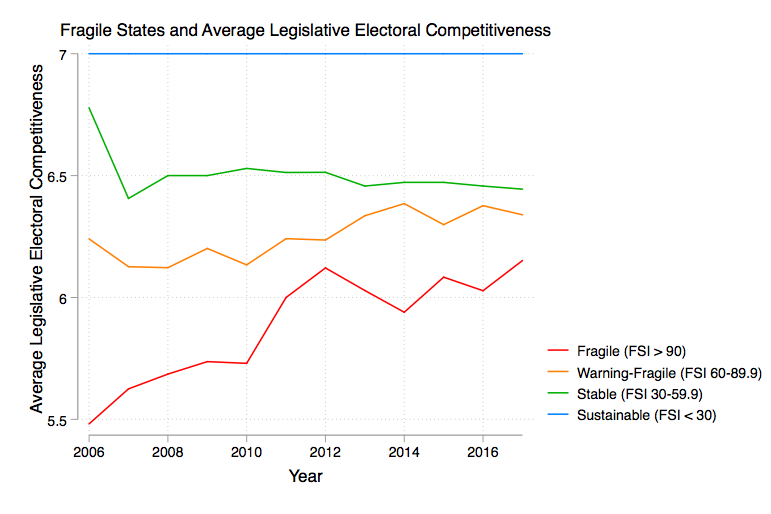

A key factor refers to democratization and is measured using the number of parties contesting and winning seats in the legislature. Previous studies have shown that states with the least political competition are the most vulnerable to state failure. The highest value of 7, by contrast, corresponds to legislative elections in which multiple parties run and win seats, and the largest party gets less than 75% of the seats.

Latin America has high electoral competitiveness

Latin America approaches this highest value. Strong political competition is a point of strength for the region, which has advanced in terms of competitiveness for both legislative and executive elections. In most countries dominance by single parties has become a relic of the past. Indeed, with elections contested by multiple parties, the region very closely approaches that level which, according to the DPI metrics, puts it in line with sustainable democracies.

Another important indicator of the health of political institutions is a relatively simple one to measure: the average age of political parties. This is based on the rationale that party age captures both the institutionalization of parties, as well as experience governing. A state where all parties are new means that, at best, all potential leaders are inexperienced. New parties also are more likely to spend government money to win elections, rather than considering the importance of long-term stability and the development of institutions. Here, Latin America fares less well. Though it trails only Southeast Asia among developing regions in the average age of political parties at just under 40 years, it still lags considerably those countries deemed to be sustainable with an average party age of between 65-80 years.

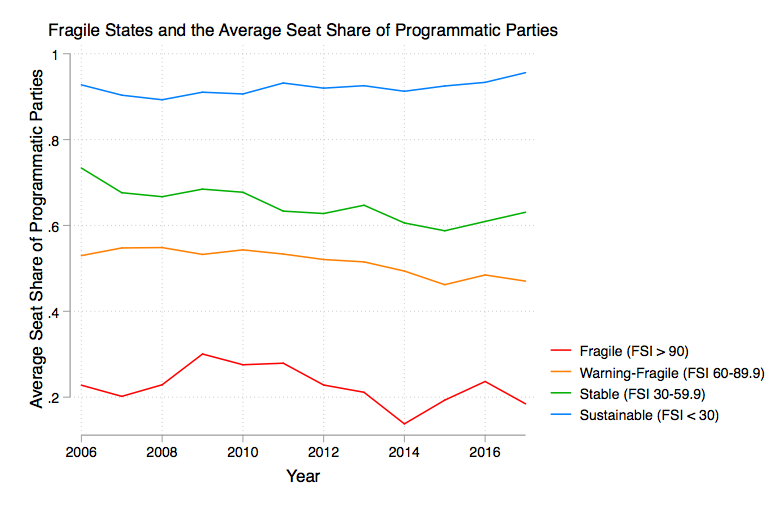

The risk for Latin America of parties without ideology

Lastly is the existence of party ideology, or what is commonly referred to as programmatic parties. This is where Latin America is at its weakest. The important issue is not so much whether parties are left-wing or right-wing. It is more whether they have an identifiable economic policy platform at all; whether they can forge consensus and keep their promises, enhancing accountability with voters. Unfortunately, since at least the late 1990s, non-programmatic parties have been on the risein legislatures in the region. These parties are often linked to populist and charismatic leaders, more inclined to use government handouts rather than ideas to win elections. And their growth is a source of potential instability.

The reality, however, is that very few states are either “sustainable” or “fragile” in Latin America. As pointed out in a recent book, the vast majority are in intermediate categories. The DPI allows us to zoom in on which institutional factors make the region most vulnerable and which states are weaker than others. The conclusion is that, while Latin American democracies are more robust in many regards than most in the developing world, there is still great variety among them and a long way to go for the region as a whole to reach the institutional stability of the mature democracies, like in Canada or Western Europe.

*Guest Authors: Arjun Chowdhury is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of British Columbia. His book, The Myth of International Order: Why weak states Persist and Alternatives to the State Fade Away, has just been published by Oxford University Press.

Cesi Cruz is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and the Vancouver School of Economics at the University of British Columbia and teaches in UBC’s School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. She is a key collaborator with the IDB on the Database of Political Institutions (DPI).

Leave a Reply