This year’s update to the Database of Political Institutions marks its 17th year of tracking institutional and electoral data for countries from around the world, and the second update at its new permanent home at the IDB. Researchers at the World Bank Development Research Group first compiled the database in 2000, coding institutional and electoral variables for 180 countries starting in 1975. Since then, the database has been cited more than 3000 times, across a wide range of disciplines and subfields.

As the Database of Political Institutions (DPI) heads into its second decade, it is a fitting time to reflect on what we have learned about measuring institutions for the last 17 years. In addition, the proliferation of other datasets and tools for measuring political institutions, including DPI, has led to an increasing focus on institutional trends as a key determinant for understanding economic outcomes and development. Nowhere is this link more evident than studying the experience of Latin American countries.

Democratic institutions in Latin America are maturing

In examining the broad trends in the region since 1975, one overarching theme has been the maturing of Latin American democratic institutions. While there are certainly stories of individual countries moving backwards, the trend towards greater political development and institutionalization stands out.

One measure of increasing institutionalization is the strengthening of democracy and the emergence of functional and competitive electoral institutions. This is crucial because one of the key findings in the literature is that when it comes to democracy, experience matters. Young democracies tend to be more corrupt, exhibit less rule of law and display lower bureaucratic quality. They also feature poorer long-term planning, with politicians who splurge on popular projects before elections, rather than carefully budgeting for development.

This greater maturity is reaping rewards. Even though dramatic reversals in democratization make headlines, the overall story is a simpler one of growth and steady progress towards democratic consolidation. For a number of indicators tracked in DPI, the region is shaping up to be the most electorally competitive—and indeed, democratic—in the developing world.

Dominance of one party is becoming a relic of the past

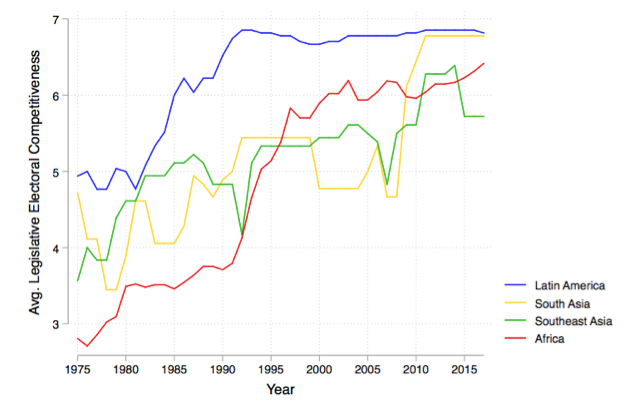

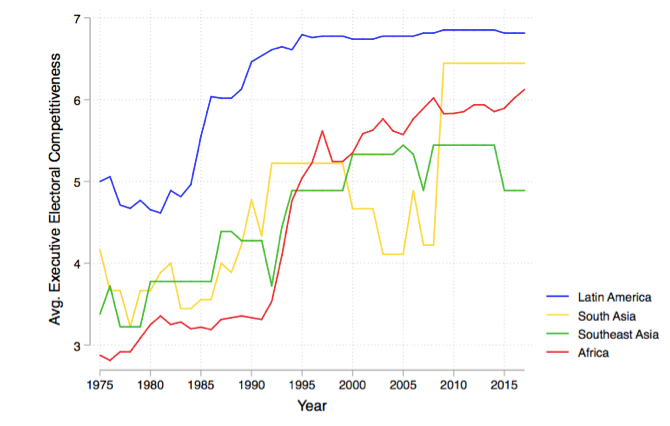

As can be seen from Figures 1 and 2 below, as a region, Latin America has steadily advanced in terms of electoral competitiveness for both legislative and executive elections. That is to say that in the vast majority of countries multiple parties now contest elections and can win: that dominance by single parties, backed by repressive force, fraud or government media monopolies, is increasingly becoming a relic of the past.

Figure 1. Average Legislative Competitiveness

Figure 2. Average Executive Electoral Competitiveness

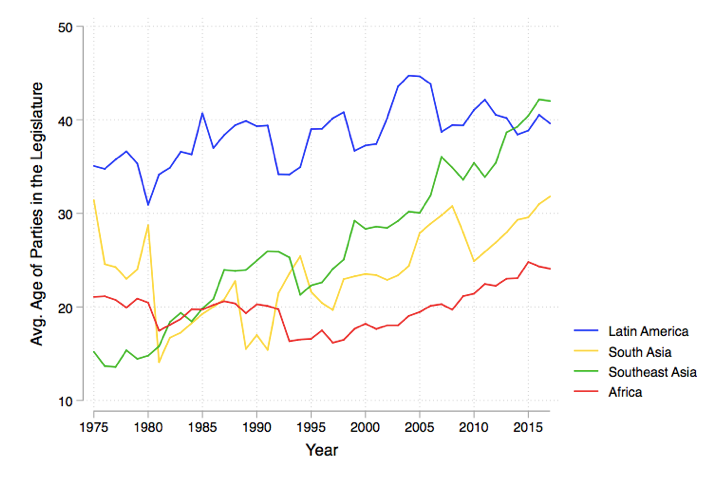

Meanwhile, the political parties themselves are becoming more institutionalized. The Latin American parties that entered the political scene in the mid-1900s as relative newcomers to politics are now the seasoned veterans of the developing world. Moreover, this strength has not come at the expense of electoral competitiveness. Ruling parties are not only becoming more entrenched and established, but opposition parties as well. In fact, in many countries, the vote shares of the formerly dominant parties in the region have declined, contributing to the trend in electoral competitiveness of the region as a whole.

Figure 3. Average Age of Parties in the Legislature

The period covered by the database has coincided with challenging economic times. Recessions and increasing economic inequality have rocked the developing and developed world. In some areas, those economic hardships have gone hand-in-hand with declines in democratic institutionalization or an increasing turn to nationalist parties. But looking at the evidence, this has not been the case for Latin America. While economic suffering has caused some backsliding, the reaction of the region in general has been to increaseelectoral competition and open up politics to new voices.

Latin Americans freely vote out parties that fail them

We have read in recent years about coups and tanks in the streets in Asia, the Middle East and Africa. But citizens in most of Latin America are freely voting out parties that they perceive as failing them, and, as they do, choosing among a greater diversity of parties with established ideologies and platforms.

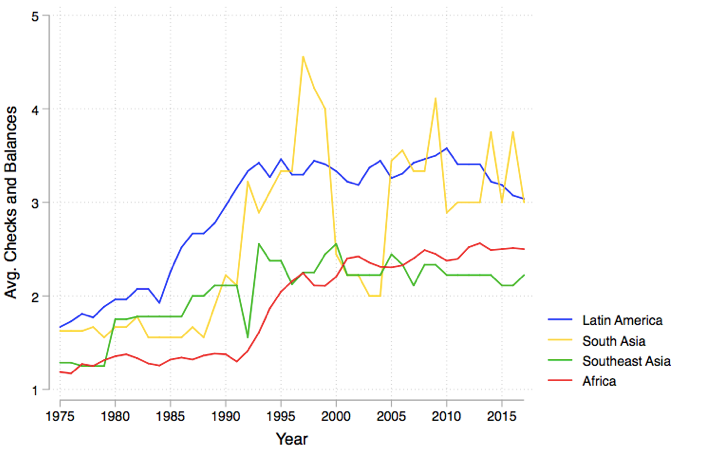

To be sure, many countries in the region still feature so-called clientelist parties, experts in the use of patronage and vote buying to win elections. And since the 1990s, there has been a growth in the region of parties built around charismatic and populist leaders, rather than ideas and ideologies. But the tradition of peaceful, constitutional change is now deeply entrenched. Consider, as but a few examples, the end of the 71-year dominance of Mexico by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) after the triumph of the National Action Party (PAN) in the elections of 2000 or the loss of the Colorado Party’s six-decade dominance of Paraguay after the elections of 2008. Or the relatively strong system of checks and balances that keeps autocrats throughout the region from monopolizing decision-making and stealing elections.

Figure 4. Average Checks and Balances

In short, Latin America has moved steadily towards democracy since the military dictatorships of the 1970s and early 1980s. While clientelism is still a force to be reckoned with and government performance lags in areas ranging from the professionalism and autonomy of the bureaucracy to the independence of the judiciary, the region has long been one of lively electoral competition at both the legislative and presidential levels, enjoying freedoms that much of the developing world could only dream of.

In subsequent blogs, we will be using the DPI to look at some of the components of democracy in greater detail along with case studies that illustrate both the challenges still to overcome and the considerable progress made to date. Stay tuned.

*Guest Author: Cesi Cruz is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science and the Vancouver School of Economics at the University of British Columbia and teaches in UBC’s School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. She is a key collaborator with the IDB on the Database of Political Institutions (DPI).

Leave a Reply