![]()

By Mauricio Báez and Katherine Poole

For 71 years, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) held sway over virtually every aspect of Mexican life. It was, in the words of writer and Nobel Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, “the perfect dictatorship.” But Mexico has undergone a dramatic evolution. Since 2000, the PRI has alternated in power with the right wing National Action Party (PAN). Different parties now compete in Congress, and key democratic institutions, like the National Electoral Council, function impartially and independently. Democracy in the most important ways has matured and deepened.

With Mexico about to celebrate a crucial presidential election July 1, it is worth considering how this came to be. A valuable means of doing so is through the Database of Political Institutions (DPI), a tool housed at the IDB with more than 100 variables for examining checks and balances, political stability, and other factors bearing on the functioning and health of political institutions worldwide. What we see using the tool for Mexico is a country with unique characteristics, which nonetheless has partaken of the trend towards greater political development and democracy enjoyed by most Latin American nations in recent decades.

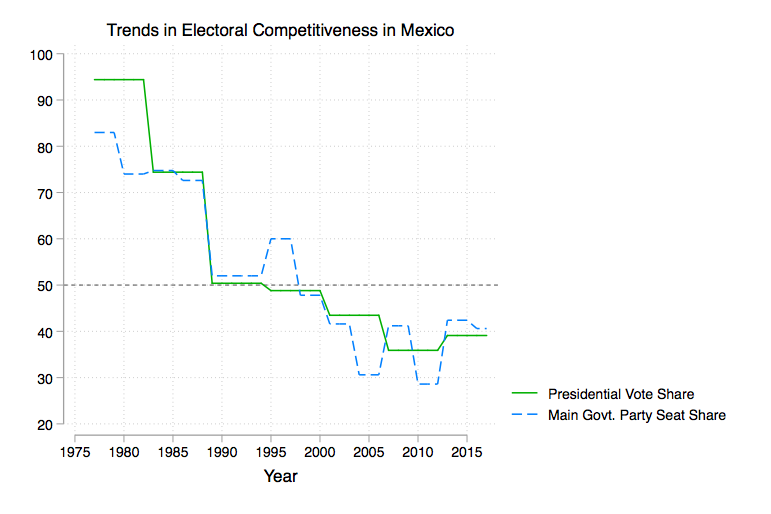

There’s no doubt Mexican democracy is getting more competitive. Looking at data from the DPI, we see the steadily declining fortunes of the PRI in presidential races, from winning elections in the 1970´s with more than 90% of the presidential vote to less than 40% in the 2012 elections as oppositions parties became increasingly viable options.

A turning point came in 1995. That year the PRI agreed to negotiate with the opposition to create the independent Electoral Institute entrusted with managing elections. As a result, the opposition ended up getting morefunding. In 1997 the PRI lost its absolute majority in Congress. Since then, no other political party has had an absolute majority, and any major legislation must be negotiated in congress among opposing parties. That has made a critical difference. President Vicente Fox, the first non-PRI president, sought to launch a set of ambitious reforms, including the construction of a new airport for Mexico City. But the initiatives failed because of a lack of opposition support.

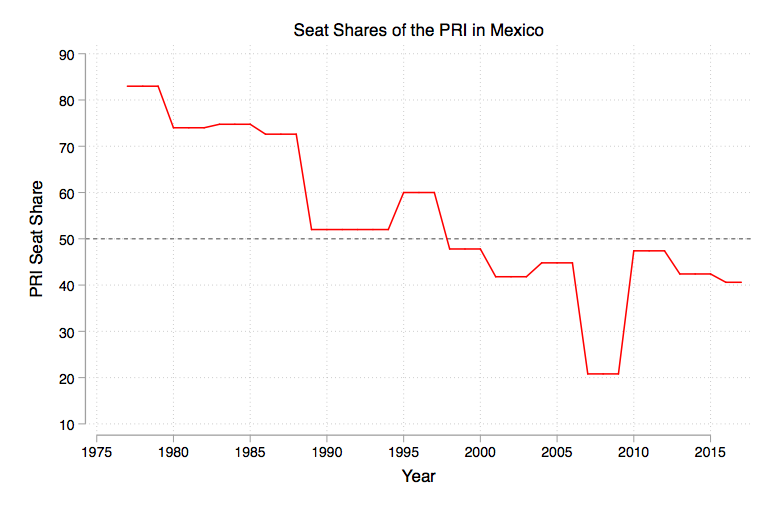

The DPI clearly shows this growing dispersion of power. We can see it reflected in the PRI’s fortunes. Figure 2 demonstrates the PRI’s decreasing congressional representation, consistent with the party’s decline in presidential vote share. The low point for the PRI in Congress came in 2006, when the presidential race was contested for the first time by two opposition parties, the PAN and the left-wing Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD). Yet, by the time of the midterm elections in 2010, the PRI had almost recovered its near-majority, perhaps because of the PAN’s unpopular national security policies.

Still, the party had to contend with the diversity of political forces that characterized the new era. In 2012, after 12 years in opposition, it was back in power. It not only won the presidency but also took the largest number of seats in both the lower Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Nonetheless, this did not amount to an absolute majority, and, unlike the old days, it had to work with its opponents to achieve its agenda.

Given the risk of Congressional paralysis, the three main political parties signed a national agreement called the Pact for Mexico, which encompassed a set of free market reforms that previous administrations had desperately tried to pass. These included opening the telecommunications market and overturning a ban on private investment in the energy sector dating back to the 1930s. Despite the popularity of the agreement, the three political parties that signed it were punished in the midterm elections after a series of corruption scandals. All three lost seats in Congress, and a newly formed party called MORENA capitalized on the situation, rapidly becoming an important player in the upcoming elections.

Now everything is ready for a new episode in Mexico’s young democracy. According to several polls, the front-runner is MORENA with Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who is running for the third time as candidate. Thirty-nine-year-old Ricardo Anaya is in second place, running for the PAN, which has formed a coalition with two left wing parties: PRD (former party of López Obrador), and The Citizens Movement. In third place stands the PRI represented by José Antonio Meade.

How this will all shake out cannot be known. The road ahead in Mexico’s political journey is uncertain. But multi-party participation, a fundamental trait of a healthy democracy, has taken root. It is possible that MORENA might win an outright majority in this election and not have to form a coalition. But given the trend in rising electoral competitiveness, coalitions do seem increasingly likely in the future, necessary to fulfill ambitious campaign promises.

Guest Authors: Katherine Poole Lehnhoff is a recent graduate from the University of British Columbia in the Program of International Relations and Political Science, with a special interest in international and sustainable development.

Mauricio Báez Sedeño is an undergraduate student of Economics at the Tecnológico de Monterreyand the University of British Columbia Joint Academic Program. He is currently working as an intern at the Permanent Mission of Mexico to the WTO.

Katherine and Mauricio have both studied under Cesi Cruz, an assistant professor jointly appointed in the department of political science and the Vancouver School of Economics at the University of British Columbia. Professor Cruz is a key collaborator with the IDB on the Database of Political Institutions (DPI).

Leave a Reply