The crash on the New York stock exchange in 1929 brought depression to the world. That is probably why when the global financial crisis broke in 2008, some observers thought the contagion originating in New York would again spread south, causing a collapse in Latin America and the Caribbean.

But that didn’t happen. Why? The region’s internal situation in 2008 was “lean and mean,” explained Harvard University Professor Carmen Reinhart. Foreign currency debt had been falling steadily, and domestic debts, both public and private, were at a low as the region’s economies, stoked with fiscal and external surpluses, had been reducing debts for years.

An external factor also played an important role. China was growing at around 10%, and that robust pace allowed it to support global growth, despite what was happening in the United States and Europe, and fuel the high commodity prices that were a boon to Latin America and the Caribbean.

Different conditions from the last crisis

Today, none of those conditions are present. While the world may dodge another recession, a persistent global slowdown will likely affect Latin America and the Caribbean, which is currently much weaker in its ability to withstand external shocks than a decade ago.

Professor Reinhart, an expert on financial crisis, delivered that sobering message in her keynote address to the 50th meeting of the Network of Central Banks and Finance Ministers, a forum established by the IDB’s Research Department 25 years ago to promote high level discussions of macroeconomic and financial issues and stimulate the Department’s research and policy advice. In her speech during the Oct. 16-17 meeting at the IDB, Professor Reinhart looked back at the exceptionally high growth Latin America and the Caribbean experienced from 2003 to 2013 and explained that “this time is different,” with risks abounding both globally and internally.

At the global level, the advanced economies lack the firepower they once had. That is to say, they have limited monetary and fiscal tools to confront the global slowdown. As China undergoes a structural transformation, it also is slowing down. It is less able to support high commodity prices and global growth and less able to supply the capital outflows that serve as inflows for emerging economies, including those in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Low interest rates

Slower global growth also may mean more long-lasting, low global interest rates. That is a positive factor in and of itself for Latin America and the Caribbean. But those low rates could delay needed fiscal reforms and are unlikely to be as much of a benefit to the region as they were before because of other external factors, like lower commodity prices and weaker global growth.

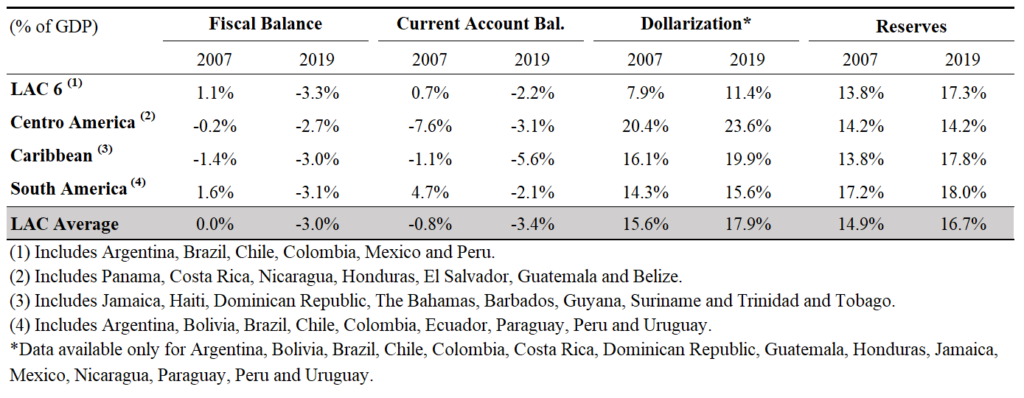

The region, meanwhile, is suffering from its own share of internal weaknesses. It has higher fiscal deficits, higher current account deficits and a higher proportion of its debt in dollars than it did before the financial crisis of 2008. Countries do have higher international reserves than a decade ago. But those are unlikely to compensate for the risk that the region’s fragilities entail, according to estimates from our latest Macroeconomic Report.

Factors Affecting Vulnerability to External Shocks

In short, though Latin America and the Caribbean will probably not suffer from shocks as severe as those from the global financial crisis of 2008, the region is more vulnerable than it was back then with a less favorable external and internal environment. “I don’t think we are in Kansas anymore,” Prof. Reinhart said, paraphrasing a famous article by Carlos Diaz-Alejandro (1984) on the Latin American debt crisis. That article explained how the region withstood the 1974- 1975 world recession almost unscathed. But, like the cyclone that upended Dorothy and Toto’s world in the Wizard of Oz, the 1981-1983 debt crisis transformed the internal conditions of the region and led to the Lost Decade of the 1980s. Today, strong winds have again changed the environment, moving the region from the safer place of 2007 to a more alarming world of low growth, weak commodity prices and trade wars.

The challenge ahead

The challenge is to rebuild the internal buffers that were so effective in the past in protecting the region from external shocks. Ensuring financial and macroeconomic stability is a prerequisite for more steady progress towards higher income levels. But that may not be enough. The region now “looks tired,” because reform efforts have stalled, according to Professor Reinhart. It is a reminder that if Latin America and the Caribbean hopes to grow faster, reduce income inequality, and achieve greater social cohesion, it must move forward with reforms to increase productivity and investment (see, for example, 2018 Macroeconomic Report).

Leave a Reply