Debt levels in Latin America and the Caribbean increased steadily during the last decade and soared in 2020 with the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching 72% of GDP. In response to the pandemic, countries mobilized considerable resources to support families and firms. Since 2020, debt ratios have declined as economies recovered and fiscal deficits were shaved. Still, with falling growth rates, higher interest rates and tighter financial conditions the future looks challenging to say the least.

The relationship between growth and the real interest rate is a critical factor in understanding debt dynamics and gauging how fiscal balances need to adjust to maintain debt sustainability. The interest rate-growth differential (or “r-g” in mathematical terms where r is the real interest rate and g is the real growth rate) measures the difference between the cost of credit in real terms and growth. When growth exceeds the interest rate, countries can run fiscal deficits and still keep debt ratios stable. But when growth is lower than the interest rate, countries need fiscal surpluses to prevent debt from exploding.

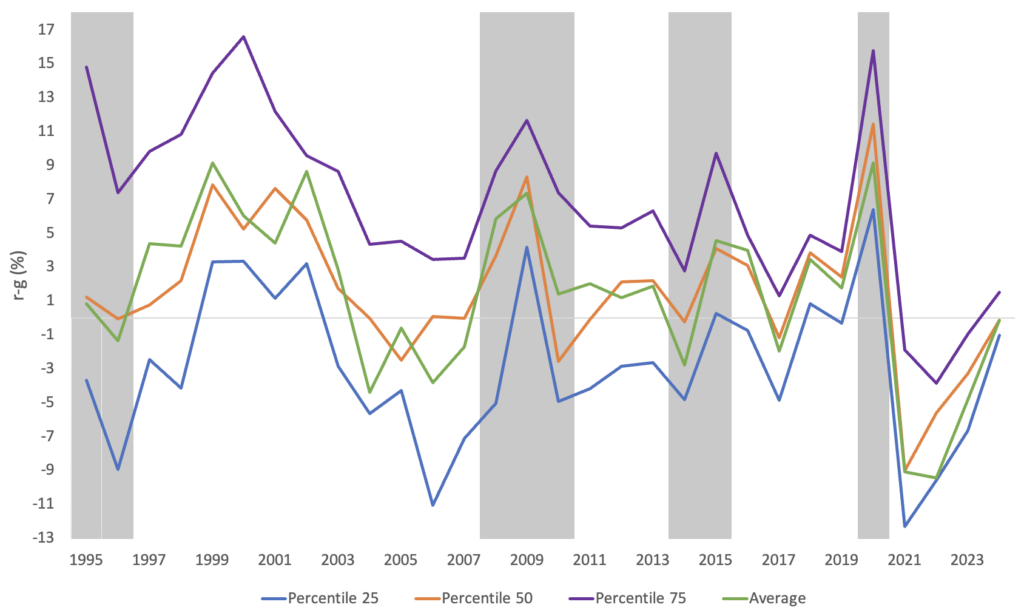

Interestingly, the sharp rise in inflation after the pandemic meant that real interest rates (which are nominal interest rates minus inflation) fell. Figure 1 shows that in 2021 and 2022 growth was clearly above the level of real interest rates for most of the region’s economies, resulting in falling debt ratios despite fiscal deficits. Still, at the end of 2022, the median debt-to-GDP ratio was 60%, above IDB estimates of what constitutes a prudent level.

Looking Forward to 2023 and Beyond

Higher inflation in advanced economies prompted significant increases in global policy interest rates. Together with banking sector stress in the US and in Europe, it may lead to depressed growth and tighter credit conditions. While China has been recovering from its zero COVID policy, its growth rates will be well below the boom years of 2002 to 2012 when it grew at an average of 10% per annum. This suggests, failing a concerted set of policies to increase growth, Latin America and the Caribbean may only grow at the rather meager estimates of potential growth (around 2.5% per annum).

The higher cost of financing may stifle the region’s growth prospects. The US 10-year bond yield surpassed 4% in 2022 after being well below 3% for most of the last decade. The yield of sovereign bonds issued in Latin America and the Caribbean reached 9% in 2022, driven by the higher global rates and a modest rise in spreads. As old debt with lower interest rates matures, it will be replaced by new liabilities at higher rates implying higher interest payments and a greater fiscal burden.

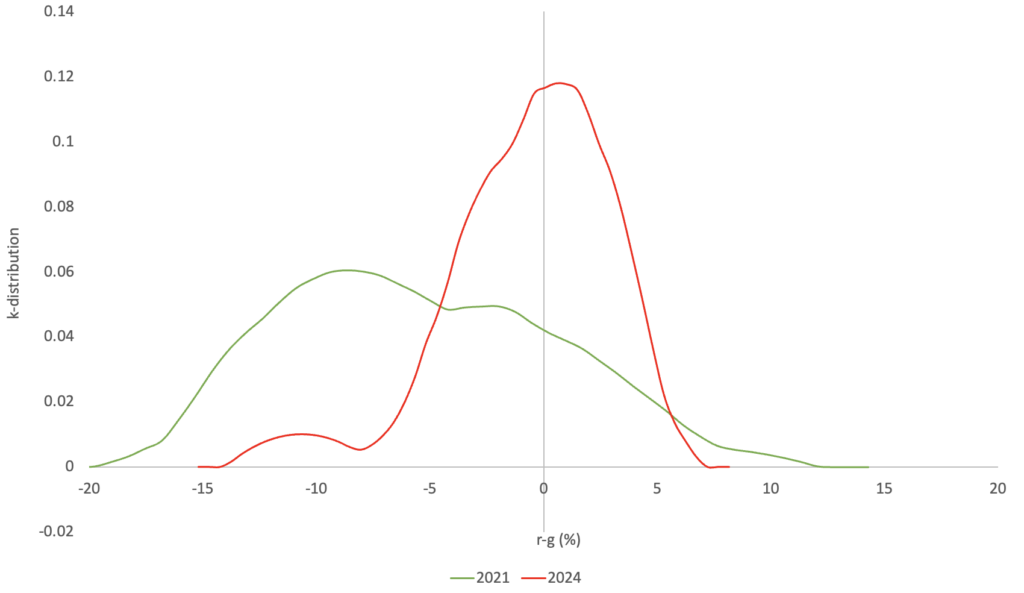

The outlook suggests real interest rates may rise above growth rates. Figure 2 shows the distribution of r-g across countries for recent years. Given the economic collapse in 2020, r-g was positive for most countries that year. As discussed, r-g then turned negative in many cases for 2021 and 2022. But by 2024 more countries (roughly half) are expected to face positive real interest – growth rate differentials.[1] Those countries will have to run fiscal surpluses in order to keep debt levels stable. On average, r-g is expected to rise by 10 percentage points of GDP from 2021 to the value that is expected in 2024.

The 2023 and 2024 curves in Figure 2 are based on the individual country projections in the IMF’s April 2023 World Economic Outlook. However, as discussed in that publication and in the IDB’s 2023 Latin American and Caribbean Macroeconomic Report, there are many potential risks. If growth in the United States (or in Europe or China) turns out to be lower than expected; if inflation is more persistent so that interest rates have to stay higher for longer; or if the stresses in banking systems prove to have a greater impact on advanced economies than those currently forecast, growth in the region may dip. Debt ratios may also rise, and the cost of servicing that debt will increase. If any of these risks are realized the distribution of r-g would shift further to the right. That would mean that more countries would need to run fiscal surpluses to keep debt ratios stable.

Reducing Debt Ratios

Given the current context of sluggish economic growth and more costly borrowing, countries should prioritize the reduction of debt ratios. This is not an easy task, but tough times call for difficult measures. The alternative could be a low-growth, high-debt trap. Dealing with Debt, the IDB’s recent flagship report, advocates for policies that would boost growth and seek greater efficiency. There are considerable opportunities to improve efficiency in both tax and revenues systems. Those would provide for more space for high quality public investment to enhance growth. Improving fiscal institutions would help make each peso of spending count and allow for a gradual approach, keeping interest rates on public debt low during the transition to lower debt.

Figure 1. Growth Adjusted Real Interest Rates

Source: IDB staff calculations based on data from Mauro et al. (2013) and IMF (2023).

Figure 2. Distribution of r-g (%)

Source: IDB staff calculations based on data from Mauro et al. (2013) and IMF (2023).

[1] The estimates are based on country-by-country projections in the IMF’s April 2023 World Economic Outlook.

Leave a Reply