Financial institutions and markets are integral in enabling transactions, intermediating savings for businesses in need of financing, allocating scarce financial resources and facilitating risk diversification. Modern economies rely on these financial institutions and markets to finance private sector development. For economies like The Bahamas, the post-pandemic recovery will be fueled in part by such domestic institutions and markets. If they are not well developed, widely accessible, and efficient, their effectiveness in aiding the recovery will not be fully realized.

Some factors that hamper private-sector development in The Bahamas include a low level of depth, concentration of domestic credit in few sectors, and restricted access and elevated costs.

1) Low depth of financial institutions

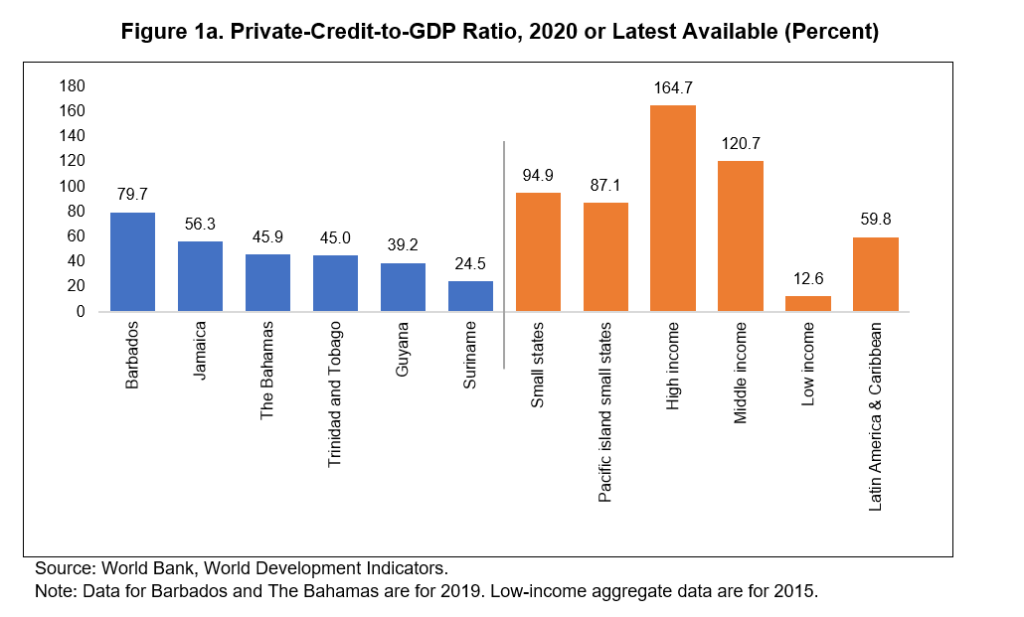

Despite being a high-income country, the depth of financial institutions is low. The share of private credit to GDP is between a third and a half of that of the country’s peers across small states, high-income countries, and within the Caribbean region (see Figure 1). Even more troubling, the depth has been on a downward trend since the 2008 global financial crisis. This underperformance is surprising considering that, like Barbados, The Bahamas is a major offshore financial center.

2) Low diversification of domestic bank credit

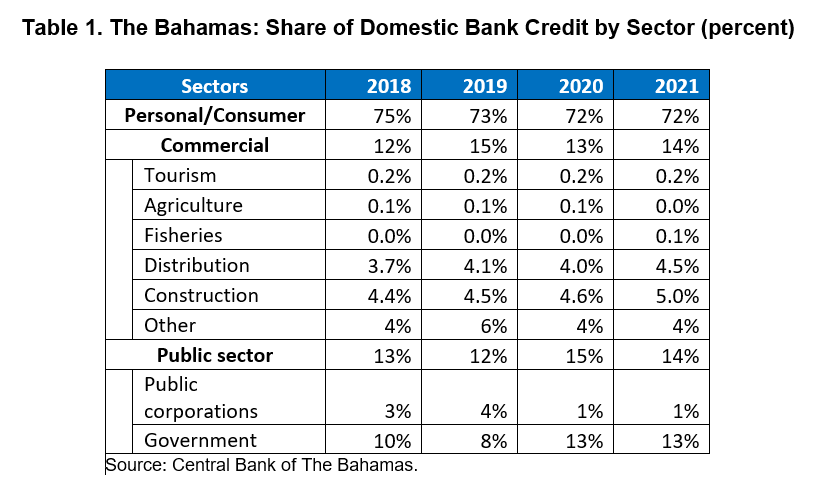

Almost three-fourths of domestic credit in 2021 was allocated to consumers (i.e., loans held by households, including mortgages). The public and commercial sectors accounted for only 14 percent each (Table 1). Both the agriculture and fisheries sectors have received negligible shares of financing from domestic banks since 2018. Since 2018, agriculture, fisheries and forestry have accounted for between 0.5% and 0.8% of GDP, which is fairly small, but is relatively consistent with its share of total private-sector credit, which has been 0.7% since 2018. Depending on their operations and financing needs, this low share of credit may be a constraint in encouraging local food production and diversifying the country’s tourism-dependent economy.

3) Low access and high cost of finance

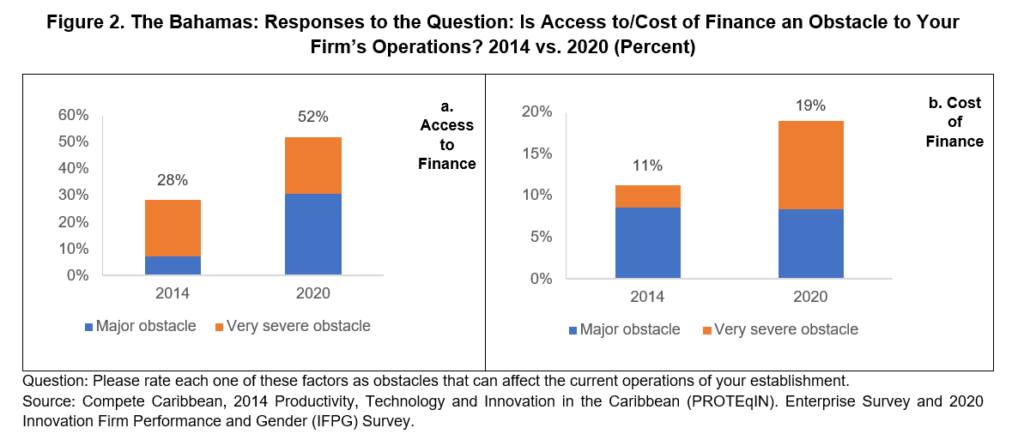

Firms have found it increasingly difficult to access and afford financing over the past eight years. In 2014, 28 percent of Bahamian firms said that access to financing was either a major or very severe obstacle to conducting business, and 11 percent characterized costs in this same way, according to Compete Caribbean’s Productivity, Technology and Innovation in the Caribbean (PROTEqIN) Enterprise Survey (Figure 2). By December 2020, these figures almost doubled to 52 percent and 19 percent respectively, according to Compete Caribbean’s Innovation Firm Performance and Gender (IFPG) Survey. The decrease in the perceived access and cost of finance in 2020 is not surprising considering the severe impact of the pandemic in the economy and the fact that domestic banks were broadly tightening their balance sheets in preparations for expected defaults and increases in nonperforming loans.

These multiple pressing challenges demand creative, bold responses

The Bahamas’ is one of a handful of Caribbean nations that is an offshore financial center. As of 2017, there were approximately 800 investment funds with over US$85 billion in assets, and many of these funds are familiar with complex and non-traditional financial instruments such as venture capital and private equity (IMF 2019). Therefore, these entities not only have the capital, but also possess expertise. More capital would mean further financial deepening, more competition would translate into lower interest rates, and wider expertise could lead to further diversification of financial products and sector exposure.

One potential avenue of exploration would be connecting promising nonbank financial institutions, such as those involved in private equity, with offshore financial entities interested in investing locally. These offshore financial entities would invest with the approval from the Central Bank to ensure that inflows of foreign currency are adequately regulated, while local Bahamian investment funds, unhampered by rules targeting non-Bahamians, could invest freely. However, for this to occur, substantial regulatory reform and government support would be needed to create this narrow yet potentially valuable bridge between the real economy and the offshore financial sector. This and other proposals are described in detail in the Second Issue of Volume 11 of the Caribbean Economics Quarterly (CEQ).

Conclusion

Although these are only a handful of the many challenges that Bahamian firms face, they are some of the most glaring and observable documented in the CEQ. These challenges have worsened since the pandemic-induced economic crisis and will potentially compete with the growing financing needs of the public sector. Although the recent introduction of the “Sand Dollar” demonstrates that the government is indeed conscious of pioneering reforms for the financial sector, more still needs to be done. Creative and bold reforms, some of which are presented in this edition of the CEQ, will be necessary to reverse the losses due to the pandemic, and narrowing the financing gap for firms.

Leave a Reply