The Inter-American Development Bank’s (IDB) Caribbean Department has published a special edition of its Caribbean Quarterly Bulletin—also detailed on our new dedicated website—focused on the evolving economic and human consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak for the region.[1] Our team of economists from across the region has been advising IDB senior management and member-country stakeholders on the potential implications of the shock, as well as policy responses best suited to mitigating its effects. The focus is on reducing the human impact of the crisis—both lives and livelihoods are at stake. Highlights from the publication are outlined below.

Crisis-Driven Challenges. From an economic perspective, the report focuses on two broad challenges:

- The domestic economic impact of social distancing measures. As necessary as these measures are, it is extremely difficult to foresee the direct economic impact from lost revenue, employment, and productivity in the “face-to-face” service sector. Naturally that impact will depend upon the duration of these measures. It will also depend upon complementary actions in the public health sector and other areas to “flatten the curve” and avoid the exponential growth of cases.

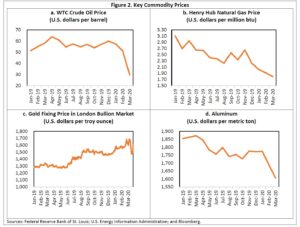

- External shocks from a combination of supply and demand factors. First, tourism is the sector most affected globally by the coronavirus—it is experiencing an unprecedented shock. Even if the travel restrictions can be removed safely, if the world is in recession, tourism will continue to be affected. Second, a combination of factors is contributing to low oil and gas prices, geopolitical on the supply side, combined with the sharp slowdown in large economies, on the demand side. Third, gold is a leading export for Guyana and Suriname. The price of gold tends to increase during periods of global financial stress, but it also becomes more volatile. Regarding imports, disruptions in transport and global supply chains might limit access to key basic goods, including food, and both intermediate and capital goods required for production and investment. Finally, risk aversion and financial turbulence make it more difficult for Caribbean countries to access external finance at a reasonable cost.

This special edition of the Quarterly Bulletin outlines key transmission channels for the ongoing crisis, and the broad policy options facing policymakers.

Click to listen to the podcast:

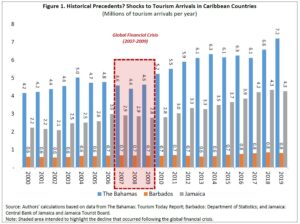

Growth of Tourism in the Caribbean. The significance of the sector for tourism-dependent economies is clear. The potential implications of the current crisis are, however, more difficult to determine. As a first step, the report highlights a new database for both air and cruise passenger arrivals going back as far as January 2000. Based on these data, we calculate that annual tourism arrivals increased appreciably from 2000 through 2019 for The Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica—by 73 percent, 37 percent, and 91 percent, respectively.

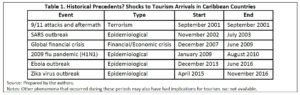

- Historical Precedents for the COVID-19 Shock? To determine whether there are historical precedents, the report identified six episodes since 2000 worthy of closer scrutiny (Table 1). A review of these episodes reveals that an appreciable decline in tourism for all three tourism-dependent economies in the region simultaneously was only observed during one of these six periods—the global financial crisis.[2] However, the largest single-year reduction observed during the entire 2000 to 2019 period was only about 6 percent (Figure 1). The near-complete shutdown of travel to Caribbean countries beginning in March 2020 would imply a much larger shock to tourism arrivals and related receipts for 2020. In this context, we conclude that there is no precedent—at least in recent decades—for the current shock to tourism in the Caribbean region.

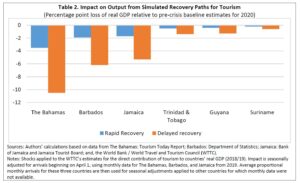

- Simulated Shocks to Tourism and their Implications for Growth: In addition to various scenarios with fixed durations and magnitudes presented in the report[3], the publication presents simulations of alternative recovery paths for tourism flows to the region: a rapid recovery, and a delayed recovery. The ‘rapid recovery’ scenario envisions a 75 percent reduction of tourism flows relative to 2019 during the second quarter (Q2) of 2020, followed by a recovery to 50 percent in Q3, and a return to 100 percent of the level observed in 2019 for Q4. The ‘delayed recovery’ scenario envisions a full cessation of tourism across all Caribbean countries during Q2, followed by a 75 percent reduction during Q3, and a 50 percent reduction during Q4. While simulations do not consider other dimensions of the shock (e.g., the loss of activity due to domestic prevention measures and illness, shocks to commodities trade, financial flows, or the positive influence of stimulus measures, etc.), they do underscore that a crisis whose apex is reached earlier in the year—that is, before the beginning of the peak season in the fourth quarter—could be considerably less damaging than one that remains acute through the end of the year (Table 2).

Shocks to Commodity Prices. As of April 17th, oil prices are less than a third of the level they were at the start of the year (Figure 2). Natural gas prices are down less substantially over the same period; however, there has been a longer-term secular decline in natural gas prices. In Trinidad and Tobago, where natural gas is ten times more important than oil, the combination of the price shock with the domestic economy effects of social distancing are hurting growth prospects. For Guyana, while prices for gold—the largest traditional export—have increased, oil production was originally expected to drive real GDP growth of over 80 percent for 2020; these estimates have been significantly revised. Gold is also the leading export of Suriname, but oil production is an important domestic sector. This coupled with a variety of domestic factors—foreign exchange shortages, political uncertainty and social distancing—are also having adverse effects on Suriname’s economy.

Crisis Implications for Financial Flows. In addition to tourism, another key shock transmission channel relates to financial flows from abroad. These flows can take the form of investments (e.g., portfolio or direct investment), other financing flows (e.g., debt), or transfers (e.g., official transfers or private remittances). The impact of the crisis on both foreign and domestic economic performance and capital markets will have implications for these flows. The report reviews these issues, with a focus on government and private finance, as well as in the context of the balance of payments.

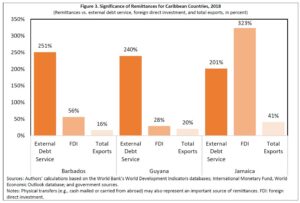

- The Importance of Remittances: One key financial channel is remittances, which have long served as important sources of foreign exchange for countries like Jamaica, Guyana, and to a lesser degree Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and Suriname. Remittances have grown considerably over the past two decades, reaching as much as 15 percent of GDP for both Jamaica and Guyana over that period. They act as an important source of financing for the balance of payments (e.g., imports from and debt repayments to other countries), which has allowed countries with relatively narrow production bases and limited or volatile export earnings to consume foodstuffs, commodities, manufactured goods, and services from abroad that might not otherwise be feasible. In this context, remittances represented the equivalent of between 201 and 251 percent of total external debt service requirements, or the equivalent of between 16 and 41 percent of total export earnings in 2018 for Barbados, Guyana, and Jamaica (Figure 3). Our report highlights a growing concern that the key source of remittances Caribbean economies tends to be migrants working in lower-skilled sectors and industries in advanced countries that seem most immediately and profoundly affected by the current crisis.

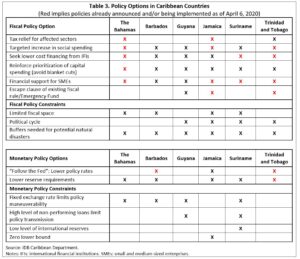

Country Specific Chapters. The report also includes country-specific sections focused on the implications for of the crisis for economic performance, as well as policy measures that have been announced and undertaken by governments since the outbreak. In the report, our country economists review policy options that remain available, and provide advice regarding some of the most promising, within the context of constraints facing policymakers (summarized in Table 3).

You can listen to more of our podcasts here.

[1] We refer primarily to the the six Caribbean countries covered by the Bank’s Caribbean Department: The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

[2] It is true, however, that there has been some variation for individual countries over other periods—for example, a deceleration of recorded arrivals to The Bahamas between 2013 and 2016.

[3] See also an earlier blog post, detailing a broader range of scenarios: https://blogs.iadb.org/caribbean-dev-trends/en/covid-19-tourism-based-shock-scenarios-for-caribbean-countries/

Leave a Reply