Summer 2021 Caribbean Quarterly Economic Bulletin

For more than a year, the Caribbean economics team at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) has focused on the potential implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for lives and livelihoods across the region. The pandemic is still with us, and the emergence of new and more virulent strains of COVID-19 has also increased uncertainty regarding the time horizon for normalization. But as vaccination programs move forward, there is now more hope than at any time since the crisis began that the cycles of lockdowns and containment measures will eventually end. However, the availability of vaccine supply remains a concern, and the pandemic continues to limit the recovery of key sectors such as tourism and local services sectors.

Our most recent edition of the Caribbean Quarterly Economic Bulletin, outlined below, focuses on two main themes: first, forecasts of key macroeconomic indicators, informed by recent expectations for the speed and breadth of tourism recovery across the region; and second, how financial sector risks have evolved since the onset of the pandemic, including a focus on policies undertaken across the region to dampen the impact of this historic shock on banks, corporates, and households.

Outsized Shock to Caribbean Countries

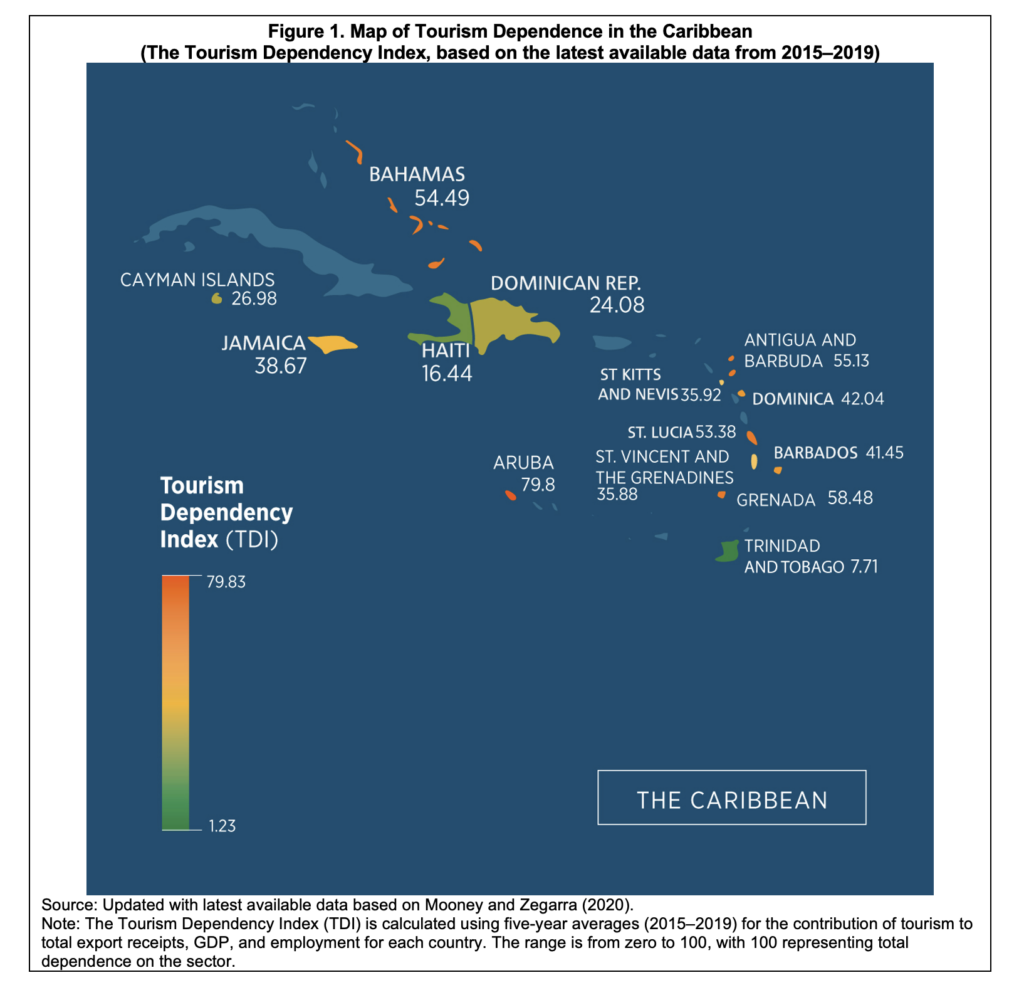

The pandemic has spawned a year like no other in terms of its implications for economic outcomes across the Caribbean. Unprecedented shocks to key sectors such as tourism and resource exports have resulted in some of the largest single-year declines in growth ever recorded for the region. This has forced governments to think seriously about economic structures, diversification, and vulnerabilities linked to specific sectors. In this context, the depth of this shock has mapped closely to the significance of key export sectors—particularly tourism dependence—for the six Caribbean countries reported on here, as well as for member countries of The Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). Many Caribbean countries are among the world’s most dependent on tourism, which has been the global sector most affected by COVID-19 (Figure 1).

Impact on Growth and Incomes

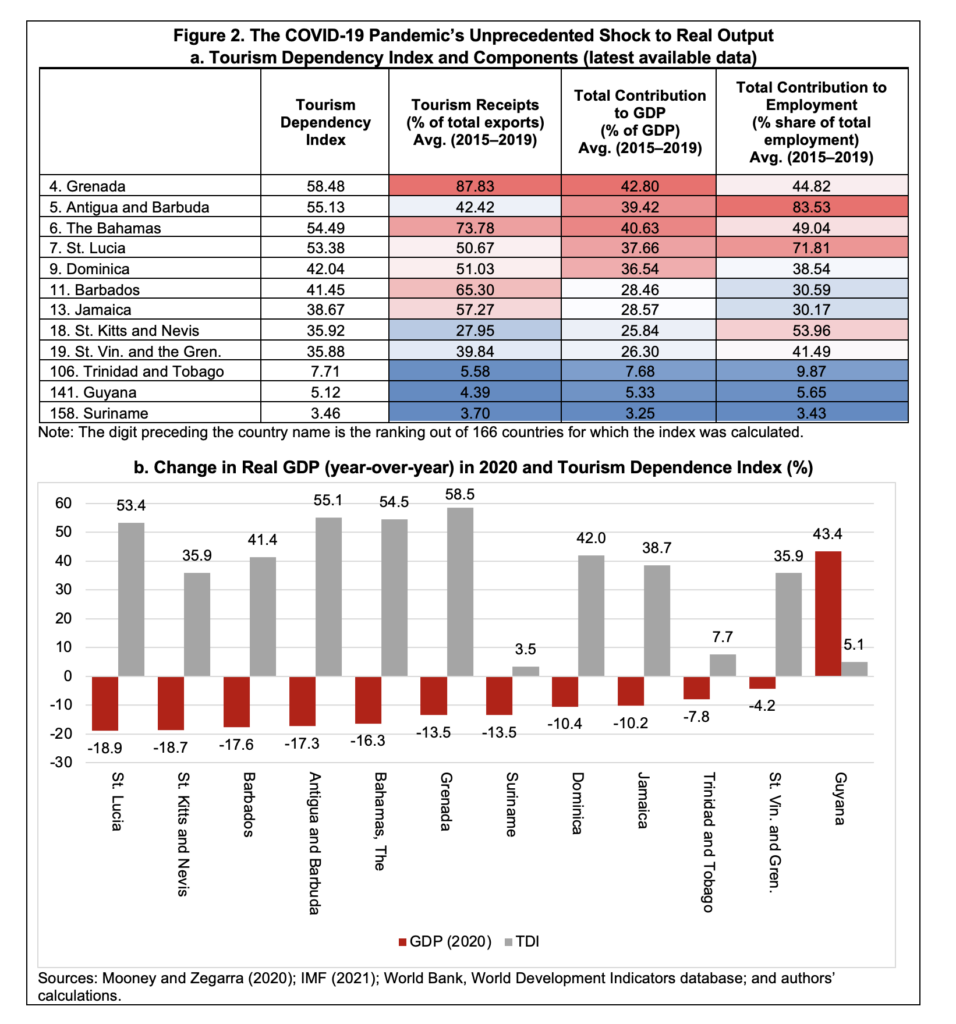

Against this backdrop, for 9 of the 12 Caribbean countries reviewed, 2020 brought a double-digit shock to real GDP—in many cases, the largest since consistent data became available in 1975. The magnitude of these shocks maps quite closely with our new measure of tourism dependency—the Tourism Dependency Index—, with nine of these countries ranking in the top 20 globally out of 166 economies in terms of their relative dependency on tourism for growth, employment, and balance of payments financing (Figure 2).

How Rapidly Can Caribbean Economies Recover?

As detailed in our previous report—Imaging a Post-COVID Tourism Recovery—, for many Caribbean countries, normalization will depend crucially on the availability of vaccines for the local population; particularly those working in the tourism sector (e.g., hotels, restaurants, transportation, etc.). Similarly, the availability of tests required in some cases for visitors to return to their home countries will also be crucial to ensure that once borders reopen, tourism offerings will remain desirable compared to other possible destinations across the world. Given these and many other complex factors affecting the recovery, considerable uncertainty remains.

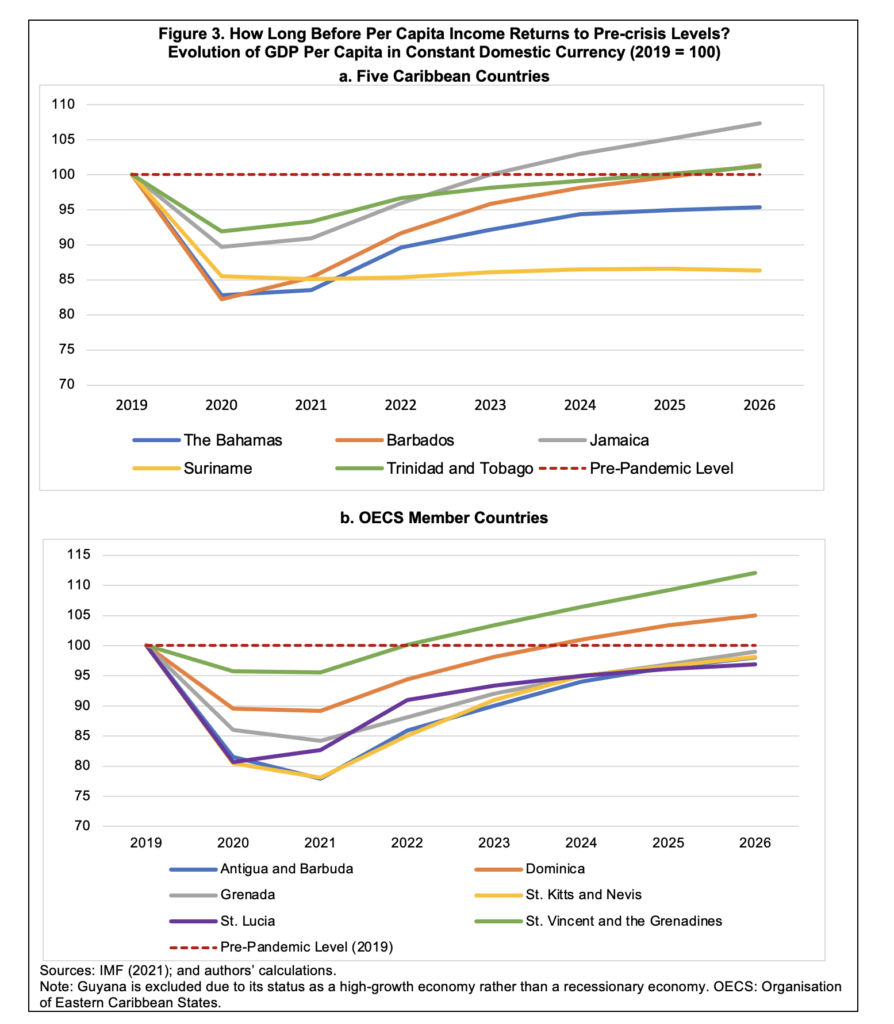

Against this backdrop, one important measure of recovery and normalization is the horizon over which per capita incomes are expected to recover (Figure 3). While other measures are important, few indicators are better able to capture the impact of the shock on citizens. Based on the latest available data and projections, only Guyana saw positive real per capita GDP growth in 2020 relative to 2019, owing to the start of production at its considerable oil discoveries. All other Caribbean and OECS countries for which data are available saw declines. Of these, only two other countries are expected to return to pre-crisis per capita income levels by 2022—Jamaica and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Most of the rest of the region’s economies may only fully recover in either 2023 or 2024. St. Kitts and Nevis and Suriname are set to experience even longer delays. In the case of Suriname, current projections envision a recovery horizon that could last well into the decade, though faster progress with macroeconomic reforms could help accelerate this transition.

Implications for Public Debt

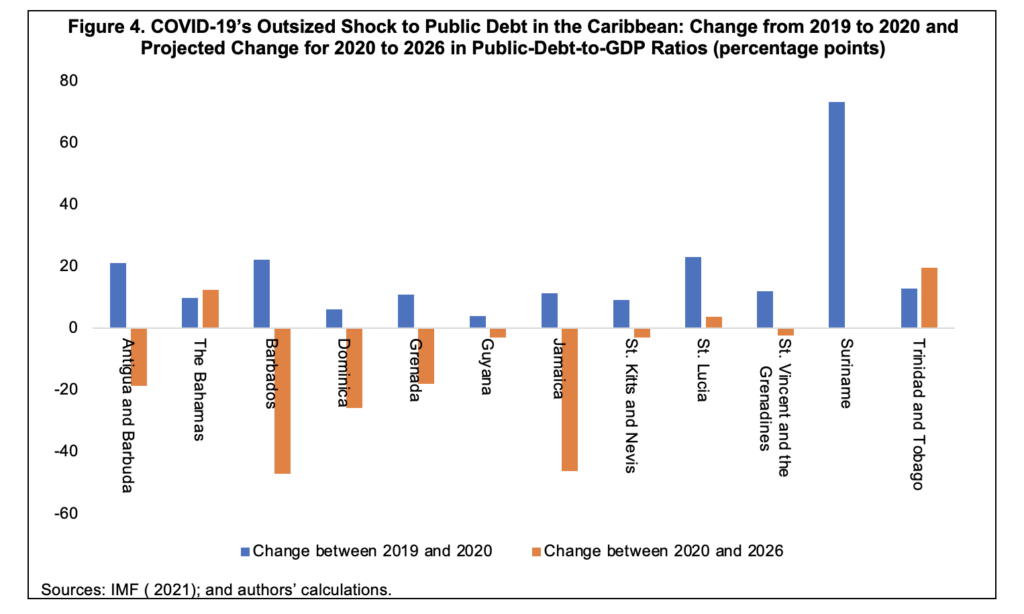

As highlighted in Figure 4, all countries in the Caribbean saw debt-to-GDP ratios increase from end-2019 through end-2020. In line with significant shocks to output, most countries in the region saw double-digit (or near double-digit) increases. For Suriname, this increase amounted to about 73 percentage points of GDP. The ratio also increased by over 20 percentage points of GDP for St. Lucia, Barbados, and Antigua and Barbuda. Dominica and Guyana saw the smallest increases among the Caribbean economies reviewed, with increases of about 6 and 4 percentage points, respectively.

Looking forward, another key question is whether the pandemic will have a lasting impact on public balance sheets. As with other variables, uncertainty remains with regard to how both the numerator and denominators of public-debt-to GDP ratios will evolve. But the IMF’s April 2021 World Economic Outlook projections suggest that there will be long-lasting implications for many countries. For example, only 4 of the 12 Caribbean economies considered are currently projected to see debt levels fall below their 2019 levels by end-2026 (Figure 4). Of these, Jamaica is expected to see the largest consolidation—of over 30 percentage points of GDP—while others like Barbados, Dominica, and Grenada are also projected to achieve appreciable improvements. For several Caribbean economies, prospects for consolidation remain uncertain, while current estimates envision double-digit increases in public debt ratios through 2026 for several economies, including The Bahamas, St. Lucia, Suriname, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. As noted above, if Suriname’s incipient economic recovery program is successful, then its debt-to-GDP ratio would follow a more favorable path in the coming years than that projected above.

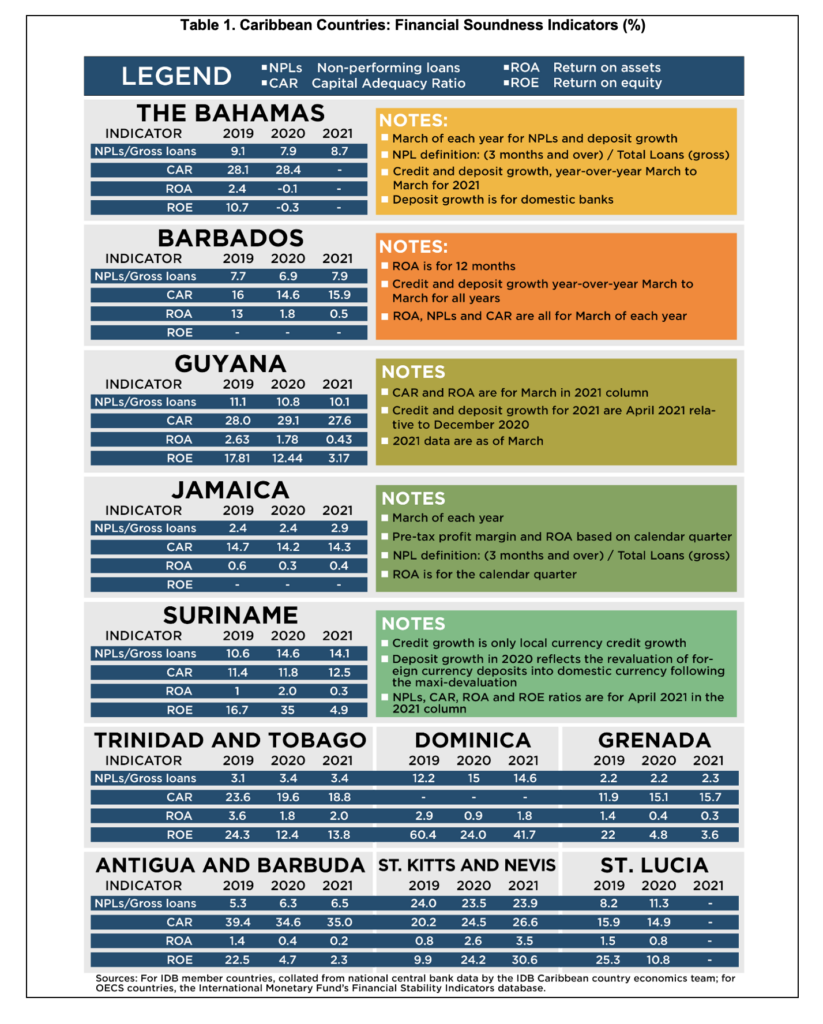

Potential Fragility in Financial Sectors?

The shock to most sectors of Caribbean economies has been considerable, which has translated into stresses affecting financial systems and markets. For the most part, financial systems were well capitalized entering the crisis (Table 1), but non-performing loans have increased to double-digit shares of total loans in several countries. Profitability, in terms of the return on assets and the return on equity, declined in most cases, and even turned negative in The Bahamas. Governments, central banks, and regulators across the region have undertaken a wide variety of measures aimed at mitigating related stresses and their implications for bank liquidity and solvency. While the jury is still out regarding the pandemic’s implications for financial systems and sectors, what is clear is that many policies and actions aimed at supporting financial stability have helped to prevent more significant implications for corporates and households.

As discussed in the report, central banks have used both conventional levers of policy—for example, policy rate reductions and lower reserve requirements—and more targeted actions to support deposit-taking institutions and other credit providers, including to the benefit of their borrowers. Such actions have included the provision of liquidity and balance sheet support—such as new term and repo facilities and broadening the definition of acceptable collateral for central bank credit—, as well as directives aimed at protecting capital buffers, including across-the-board restrictions on dividend distributions. One seemingly effective action undertaken across several countries has been the use of “moral suasion” to encourage banks to provide a wide variety of accommodations to borrowers facing cash flow difficulties that might otherwise have compromised their debt servicing capacity. Such measures have included concessional rescheduling of debt obligations, repayment moratoria or deferrals, and other adjustments that have succeeded in preventing a wave of delinquencies and defaults that could have had severe consequences for financial stability, with obvious implications for all other sectors of Caribbean economies. In the aftermath of the crisis, there will be many lessons to distill from countries’ experiences, particularly with respect to innovative policies that helped to prevent deeper shocks.

Country Specific Chapters

The report also includes country-specific sections focused on the implications of the crisis for economic performance, as well as policy measures that have been announced and undertaken by governments in The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, as well as the six sovereign member states of the OECS. In the report, our country economists review recent economic performance, policies, and risks to economies in the region.

PODCAST: Our blog authors also discuss the critical issues in Caribbean economic recovery in this podcast. Click to listen!

Leave a Reply