The COVID-19 pandemic is the most challenging global crisis since the postwar, for its public health dimension as well as its economic consequences. International trade is one of the channels of contagion of the economic crisis that will strongly affect Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

This begs several questions. Why is this crisis different? What are the channels of trade contagion? What will be the magnitude of the shock? What can we do about it?

How economically contagious is COVID-19?

The pandemic has already severely affected all the G7 economies, starting from the first epicenter of the outbreak in China. Unlike recent similar epidemics, today people’s mobility is greater, global value chains are more integrated and financial markets are highly internationalized. And this new coronavirus is more contagious than others.

The epidemiological evolution of the virus is expected to follow a typical inverted U curve in each country. However, national authorities are trying to “flatten the curve” with different strategies and at different times. And new waves of infection cannot be ruled out.

The global severity and simultaneity of the health crisis, the asynchrony of the efforts to combat it and the uncertainty about its duration leave us expecting unprecedented economic feedback effects, unusual in a crisis originating in the real sector, and comparable or greater than those of the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

LAC’s exposure to trade contagion

LAC faces simultaneous external shocks to real demand and supply and to the terms of trade.

The drop in international demand, due to lower consumption and the postponement of investment decisions by trading partners, will affect economies proportionally to their degree of openness. Sector effects can be disruptive. For example, China absorbs 79% of Brazilian soybeans or 60% of Peruvian copper.

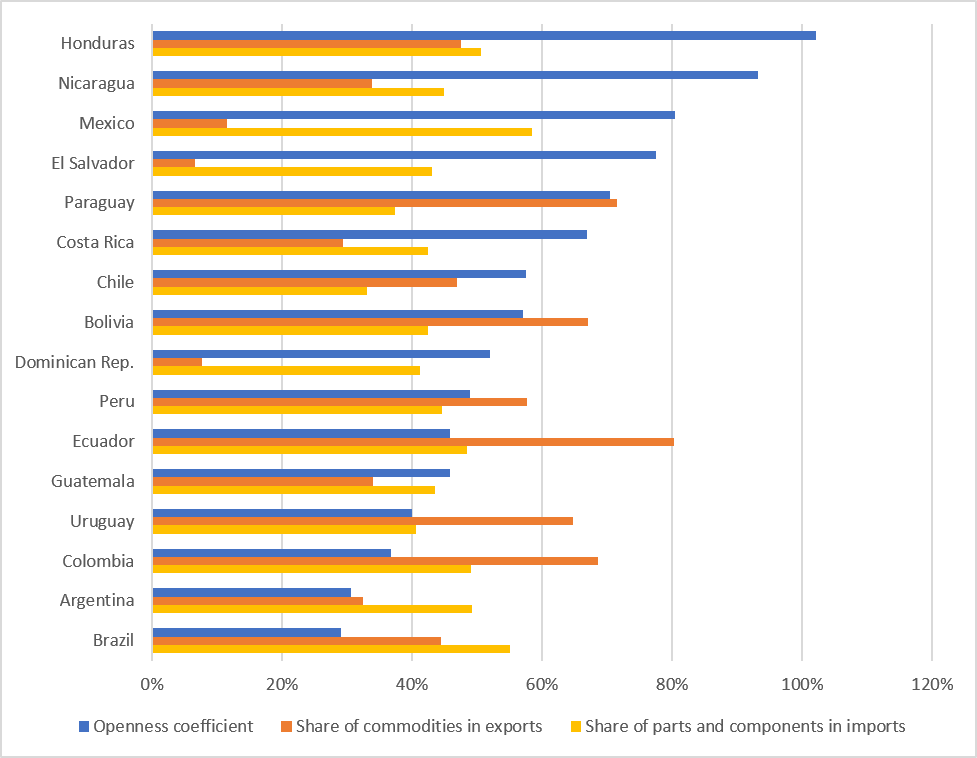

On the supply side, the interruption of production in China has already caused parts and components shortages in the electronics, auto parts, and pharmaceutical sectors in Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico, and in the textile sector in Central America. These restrictions are due to both the cessation of production abroad, and obstacles in logistics systems and at borders. The spread of the crisis to Europe and the United States will amplify these effects exponentially. Countries that import more parts and components are more exposed to these disruptions, as is shown in figure 1.

The contraction in trade volume is compounded by the fall in export prices. The average price of oil has plummeted since the beginning of the year (-60%) and other commodities are also following a downward trend, such as copper (-22%), iron (-1%), soybeans (-5%), sugar (-20%), and coffee (-18%).[1] The drop in prices will affect economies whose exports are concentrated in commodities, although some net importers could benefit.

These extraordinary factors will likely continue to operate throughout the year, leading to a sharp contraction in the value of the exports of goods, which already fell -2.4% in 2019, for the third time in the decade since the Great Trade Collapse that accompanied the Great Recession.

Figure 1. Exposure to external shock: trade in goods

(Openness coefficient, Share of commodities in exports of goods, Share of parts and components in imports of goods, in %, 2017–2018)

Source: Own calculations using UN COMTRADE data.

Notes: Openness: exports + imports of goods and services as a % of GDP; Share of commodities: exports of primary and energy products as a % of total exports of goods; Share of parts and components: exports of intermediate goods and parts and components of capital goods as a % of total exports of goods. The most recent years are only shown for countries for which complete, up-to-date data is available. Countries are ranked by openness coefficient.

Service exports will no longer be the exception

Some evidence points to the greater resilience of service exports in periods of crisis. However, this will not be the case for LAC this time.

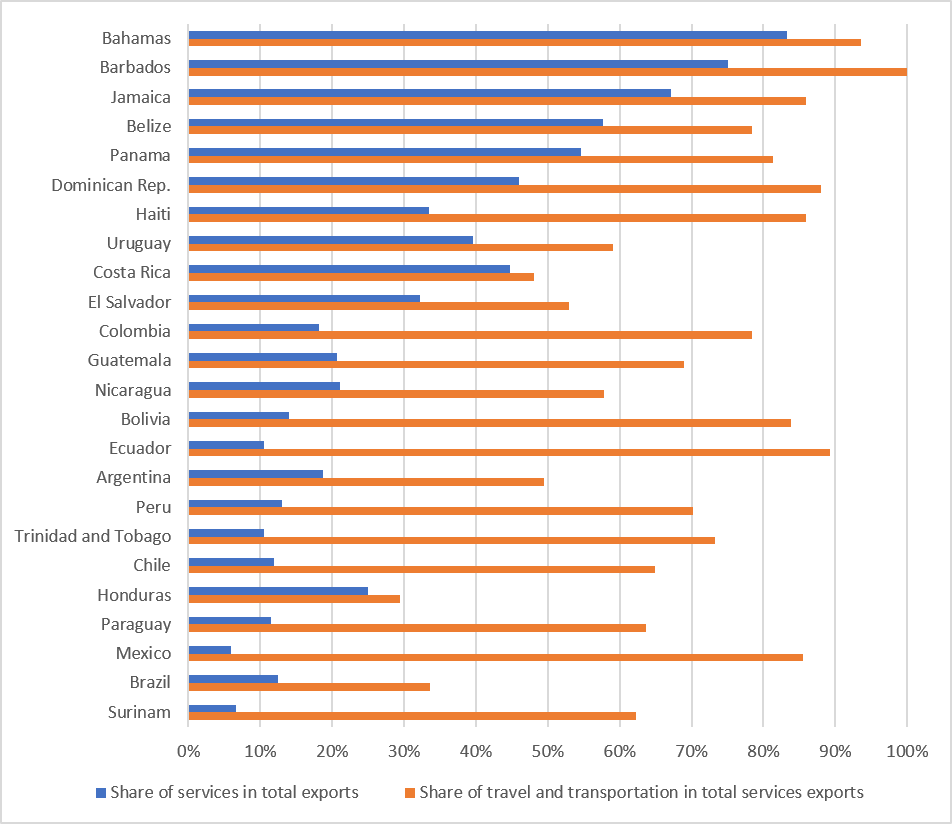

The travel (tourism) sector—which represents 40% of LAC’s services exports—will be the most affected due to border closures and the lower propensity to travel after their reopening. The transportation sector—which ranks second, accounting for 18% of services exports— will follow the contraction of international trade. Data from China illustrates the point: port traffic fell 20% in February and exports dropped 17% in January–February. Some Caribbean and Central American economies are particularly exposed to this transmission channel (figure 2).

Business and Information Technology services, particularly those delivered digitally, may prove more resilient. Some segments such as telemedicine, distance learning, or teleworking platforms may even grow. However, these account for less than 30% of LAC’s total services exports and will, in any case, be subject to the fall in external demand and supply constraints, depending on how severely COVID-19 affects the region.

Figure 2. Exposure to external shock: trade in services

(Share of services in total exports, Share of travel and transportation in total services exports, in %, 2017–2018)

Source: Own calculations using WTO data.

Notes: The most recent years are only shown for countries for which complete, up-to-date data is available. Countries are ranked according to the combined influence of the two variables considered.

In any case, service exporters face instantaneous losses since, unlike trade in goods where inventory management and compensatory trade flows in the postcrisis can be expected, generally services cannot be stocked.

A major trade shock

Although it is premature to predict the size of the economic shock, some models are useful to gauge its magnitude and to consider underlying assumptions and transmission channels.

In an optimistic scenario, the OECD estimates a cost equivalent to 0.5 percentage points (p.p.) of world GDP and a real contraction of -0.9% in global trade. In a pessimistic scenario, costs would triple to 1.5 p.p. of GDP for the global economy and the trade contraction would quadruple, reaching -3.75%.

One model that includes the epidemiological dynamics of the novel coronavirus suggests that the OECD estimates are conservative. In a global pandemic scenario of moderate intensity, GDP is expected to contract by -4.7% in Brazil, -3.5% Argentina, and -2.2% in Mexico.

Despite several criticisms to these models, the results point to a very severe impact on LAC economies and a trade contraction comparable to or greater than the Great Collapse of global trade (-15% in real terms between 1Q 2008 and 1Q 2009).

What should we do?

LAC will face a trade shock of historic proportions, which will add to the external financial and internal economic crises. Three general principles should guide the reactions of political, business and social leaders.

It is crucial for governments to associate early efforts to “flatten the curve” with measures to make this process as short as possible. For example, increasing testing capacity, improving contact tracing, and isolating high-risk individuals. Otherwise, they will have to choose between the apparent dilemma between saving lives and saving the economy, a choice that will become harder by postponing the containment measures. Acting with urgency is needed not only to save lives today, but also to limit the economic costs of fighting the pandemic and to safeguard the future of both families and businesses.

Second, it is essential to promptly remove restrictions to international trade as quickly as possible, especially for health-related goods and services.[2] Although closing borders to human traffic is plausible in the early stages of the pandemic, such closures become progressively less effective and the cost of implementing them quickly begins to outweigh the benefits, particularly when they affect the movement of goods.

Third, to prepare for the recovery of global trade, it is essential to plan ahead and not lose sight of the main lesson this crisis has already taught us: the world is inextricably connected even though the consciousness of sharing a common destiny is being lost. It will not be isolation that will allow us to prosper at the expense of others, but the capacity of each of us to contribute to multilateral solutions that make the whole greater than the sum of the parts.

Today, more than ever, it is necessary to act timely with vision, solidarity and integration.

[1] Variation in price indexes for different product varieties between 31/12/19 and 18/3/2020, based on data from Bloomberg.

[2] Examples include the elimination of tariffs, nontariff barriers, and export bans on health products, as well as active trade facilitation measures such as accelerated import licenses for these goods or measures to disinfect cargo, vehicles, and transportation equipment and implementation of health checks for drivers.

Leave a Reply