Investing in infrastructure is crucial for a country’s economic performance and growth prospects. In fact, it not only can make a difference in people’s everyday lives by providing better roads and schools, but it can actually save lives. During the last decade, Chile and Haiti provided two contrasting examples of this in the face of earthquakes due to their different levels of readiness and resilience to natural disasters.

Chile has been face to face with two catastrophic natural disasters in the last few years. Last September a powerful 8.3 magnitude earthquake caused 19 deaths and a billion dollars in material losses, according to the global disaster database EM-DAT. In February 2010, a devastating 8.8 magnitude earthquake followed by a tsunami caused more than 550 casualties and economic losses estimated at 30 billion dollars, or almost 19% of GDP. These were significant shocks, but Chile managed to get back on its feet fairly quickly.

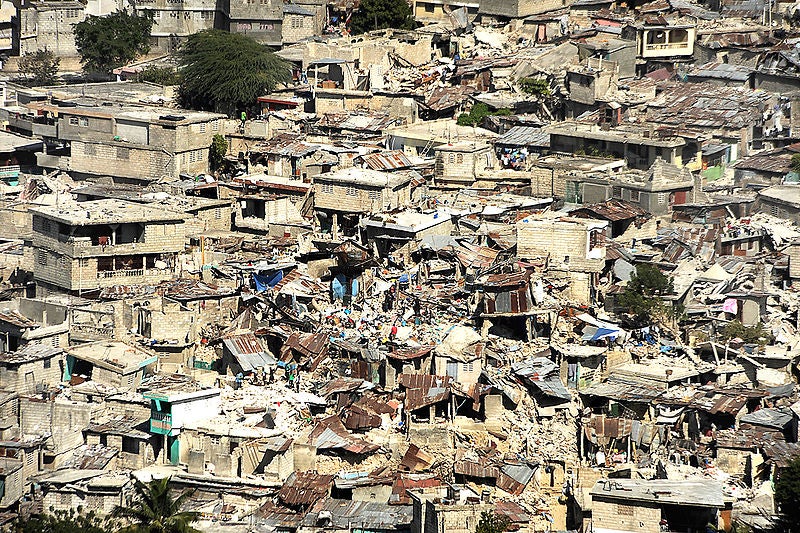

In contrast, in January 2010 Haiti was torn to pieces after a 7.0 magnitude earthquake caused more than 200,000 deaths and $8 billion in material losses — greater than the country’s GDP. Buildings, and the country’s infrastructure in general, were reduced to rubble, and about 2.3 million people became homeless, out of the country’s 10 million population. Its roads, ports and main airport were rendered useless. Its public health system collapsed. Six years later, foreign aid has funded a great amount of reconstruction work, but the country is still struggling to turn the page on that traumatic event.

A previous post analyzed the factors that made it possible for Chile to quickly recover after suffering the impact of natural disasters. One of the factors listed is “preparedness:” The South American country has invested in solid, earthquake-resistant housing and infrastructure, given its vulnerability to these kind of events. The Caribbean island, on the other hand, had precarious, feeble buildings that crumbled and buried people underneath the resulting rubble. Lacking financial muscle, Haiti had to rely only on foreign aid for its reconstruction effort. As explained in another post, foreign aid after natural disasters is never enough to rebuild a country towards a sustainable recovery.

On the surface, the comparison between Chile and Haiti is unfair because Chile is a relatively rich economy that can afford to finance good and resilient infrastructure, while Haiti is the poorest country in the region, and as such, has to deal with basic needs first. But Chile wasn’t always rich, and building its current resilience did not happen overnight.

Chile’s investment in resilient infrastructure was made possible thanks to the country’s discipline for saving, which in turn was built over decades. In other words, saving provided the resources that allowed the country to invest. Saving and investment are two sides of the same coin. But, the attentive reader may ask, why should economies care about how much they save? After all, if economies can always borrow from abroad, then national saving rates should not matter. The problem with this view is that it neglects that borrowing from abroad may be more costly and may raise the risk of crises. Foreign financial flows are fickle, and history shows that they dry up just when they are needed most. Latin America and the Caribbean is no stranger to the currency and financial turmoil generated by external debt. Many countries in the region have sought to increase the amount of saving they import from abroad to partly compensate for the limitations of having low national saving rates. But why would foreign investors be willing to provide financing at good terms if the locals are not willing to save and invest domestically? Importing saving from abroad is far from a perfect substitute to boosting saving at home. Chile in fact is a very good example of this principle: the country increased its saving rate by 11 percentage points of GDP in the period 1985-2013 compared to 1960-1984 (see Cerda et al, 2015). That facilitated capital inflows as a complement, rather than as a substitute, to finance domestic investment.

Increasing national saving is a key policy challenge for Latin America and the Caribbean. Saving enables investment. That is how saving is ultimately connected to the resilience to natural disasters. Even more importantly, saving is the path that leads toward a region with greater resilience, and where lack of capital is no longer a constraint for development.

Some of these issues are discussed in the 2016 edition of the IDB’s flagship series, Development in the Americas, entitled Saving for Development: How Latin America and the Caribbean Can Save More and Better. Click here to receive updates on this upcoming book and a free PDF upon publication.

Leave a Reply