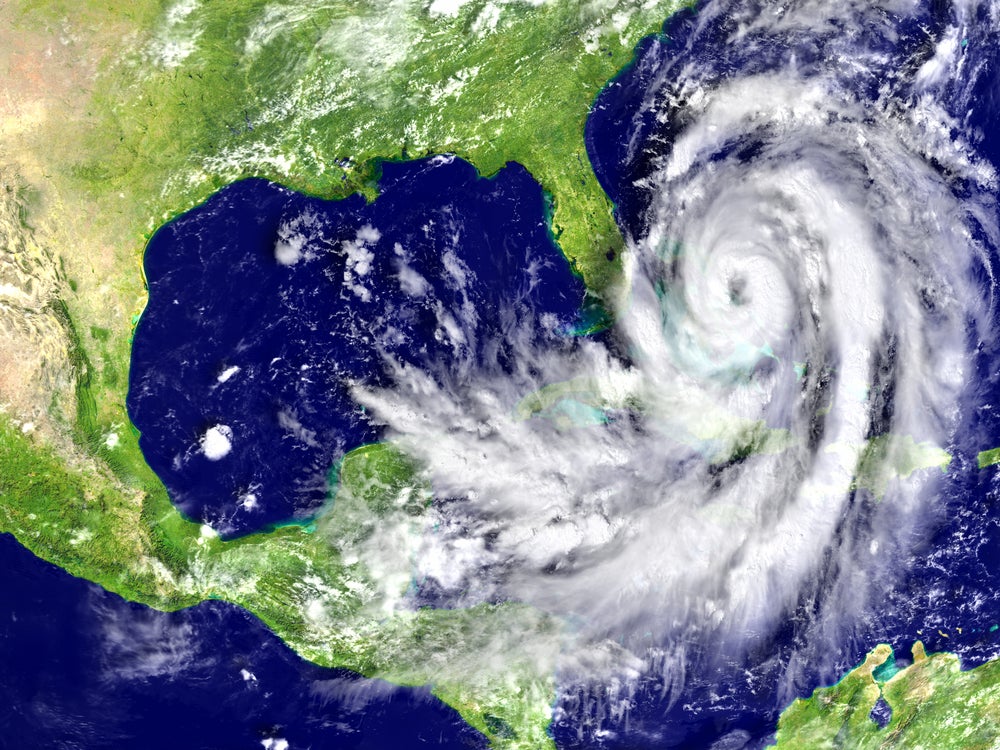

The lashing rains and 185-mile-per-hour winds pounding the Caribbean from Hurricane Irma; the toppled homes and flooded streets in Texas and Louisiana from Hurricane Harvey, with its tens of thousands of people made homeless and billions of dollars in property losses: it’s hard to imagine things getting much worse.

Unfortunately, they almost surely will. If scientists agree that it’s impossible to link one hurricane or storm to climate change, they also agree that as the waters warm, pumping more moisture into the atmosphere, and seas rise, hurricanes and storms will become more lethal. In the Caribbean basin, the number of hurricanes climbed from 15 in the 1980s to 39 between 2000-2009, according to a 2014 report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The key is being prepared. That means not only better seawalls and early warning systems. It also means better zoning, so that urban sprawl and agricultural projects don’t replace the mangrove swamps that hold back storm surge; the wetlands that absorb excess water; and the forests that bind the soil and stop rains from turning into landslides on mountains slopes. It means better sewage and drainage, among other key defenses.

It can also involve buying disaster insurance, including what are known as catastrophe (or cat) bonds. These bonds, which can be issued by governments or reinsurance companies and are usually backed by U.S. Treasury bills, though expensive, provide a key advantage. Payments are based on the severity of an event, rather than estimates of damages. They are thus made quickly and with little contention, permitting a country to stem the injury to agriculture, industry and tax collection that can often set off crippling chain reaction that can make recovery even more traumatic.

But for such a country to prepare in those ways, as we explain in a previous blog, it needs the capacity for far-reaching planning. It also has to have good macroeconomic management, so that it can save the money it needs to buy insurance, build resilient infrastructure and, after disaster strikes, rebuild whatever is lost.

Improving its economic management allowed Chile, for example, to fortify itself. The country established strict building codes and an effective, decentralized system of emergency personnel. And when an immense earthquake measuring 8.8 on the Richter scale and a tsunami struck the country in February 2010, it was ready. The disaster killed more than 500 people and generated losses of $30 billion or almost 19% of GDP. But because Chile had saved and prepared, it was able to get back on its feet relatively quickly without resorting to foreign aid, while Haiti, which experienced a similarly devastating earthquake six weeks before, is still struggling.

Most countries, of course, do eventually bounce back. There are very rare cases, such as the 1978 earthquakes in Iran or the December 1972 earthquake in Nicaragua that afflicted nations with negative growth for ten years after the event. But these events were followed by radical political revolutions that fundamentally changed their economic and political systems. This is not likely to be the case with the storms currently affecting the Caribbean basin and the United States. Still, we are in a new world with climate change, and it is difficult to predict how costly the human, physical, and economic toll will be from future severe weather events.

What is clear is that no matter how much the international community seems to mobilize in the wake of a natural disaster, its generosity will almost never be enough. As demonstrated in Haiti with the 2010 earthquake, promised aid doesn’t fully materialize or is inefficiently distributed, and the funds that do arrive are usually earmarked for disaster relief rather than helping establish long-term resilience. The countries that best recover from natural disasters are those best able to help themselves. With climate change threatening everything from rising seas and hurricanes to searing temperatures and drought, this is the moment to prepare for what appears to be the inevitability of much more extreme weather events as the century unfolds.

Leave a Reply