Part of our “behind the scenes” series of posts for our 2020 flagship publication From Structures to Services: The Path to Better Infrastructure in Latin America and the Caribbean

Improving the quality, efficiency, and productivity of water, power, and transportation could have significant benefits for economic growth and income distribution. In a recent blog, we showed that small improvements in the efficiency and productivity with which services are provided can increase regional GDP by US$200 billion over the next decade while creating jobs and reducing income inequality. These results raise the question: What public policy actions should we take to secure these benefits? The traditional response has been to focus on investing in more infrastructure: for example, roads, airports, power lines, and water treatment plants. In this post, we will explore evidence indicating that simply investing more is not enough. Regulation plays a crucial role in ensuring that the benefits of better infrastructure translate into increased prosperity.

To explore the implications of regulation, we analyzed the role of prices on infrastructure services. Prices are a key channel through which the benefits of new or better infrastructure reach users. The simulations run in the previous post assume that the economy operates with a competitive price setting mechanism. However, infrastructure services tend to be managed through regulated markets where prices are contractually predetermined. Price rigidity can prevent efficiency improvements from translating into lower prices for users.

In this blog post, we explore the implications of efficiency improvements in the context of a noncompetitive price setting mechanism. First, we simulate the effects of restricting the price reductions generated by the efficiency and productivity improvements. Specifically, we assume infrastructure service providers impose profit margins of 15% over the marginal costs of production (that is prices are 15% higher than if the prices were fully flexible and markets were competitive). This mechanism enables infrastructure service providers to “capture” a portion of the efficiency improvements, stopping the benefits generated from cost reductions from being transferred entirely to the prices consumers pay.

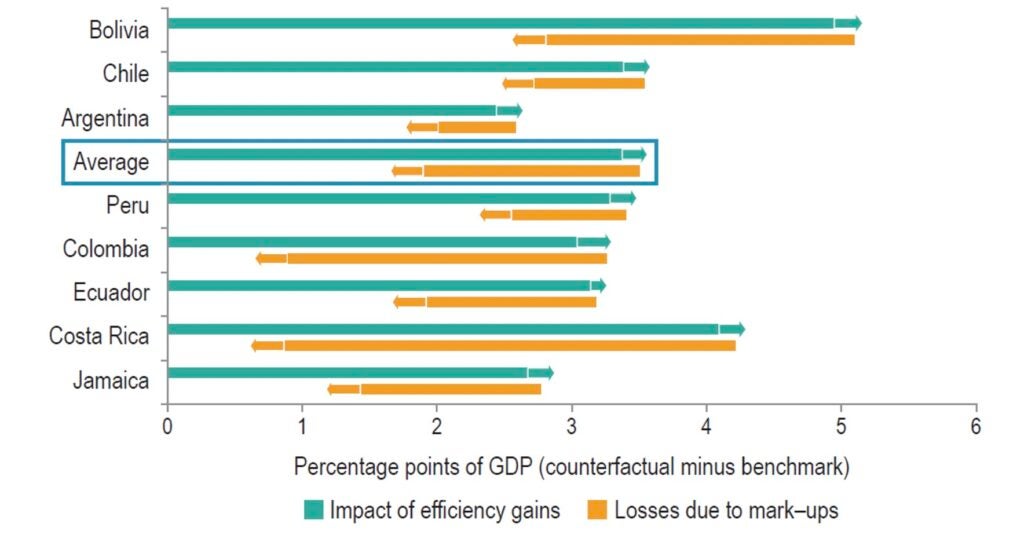

Figure 1 shows the difference in the growth trajectories, in percentage points, between the baseline scenario (that is, efficiency and productivity improvements without margins between prices and costs) and the counterfactual scenario of a 15% margin (that is, efficiency and productivity improvements with margins between prices and costs). On average, in the contrafactual scenario, countries lose 1.8 percentage points of GDP over 10 years compared to the case without margins. Losses are as high as 3.5 percentage points in Costa Rica and 2.5 percentage points in Bolivia and Colombia. The countries that lose the most are the ones that would benefit the most from efficiency improvements simulated with competitive markets and full price flexibility. This suggests that the benefits to consumers of the efficiency improvements decline as the margins between the cost of providing the service and the price paid by users widen. If these conditions of uncompetitive markets persist over time, the outcome is lower GDP growth.

Figure 1. Impact of Efficiency Gains on GDP Growth, with and without Margins between Prices and Costs

Note: The graph shows the cumulative change—in GDP percentage points—of the contrafactual scenario (that is, greater efficiency with margins between prices and costs) minus the baseline scenario (that is, greater efficiency without margins between prices and costs) over the course of 10 years.

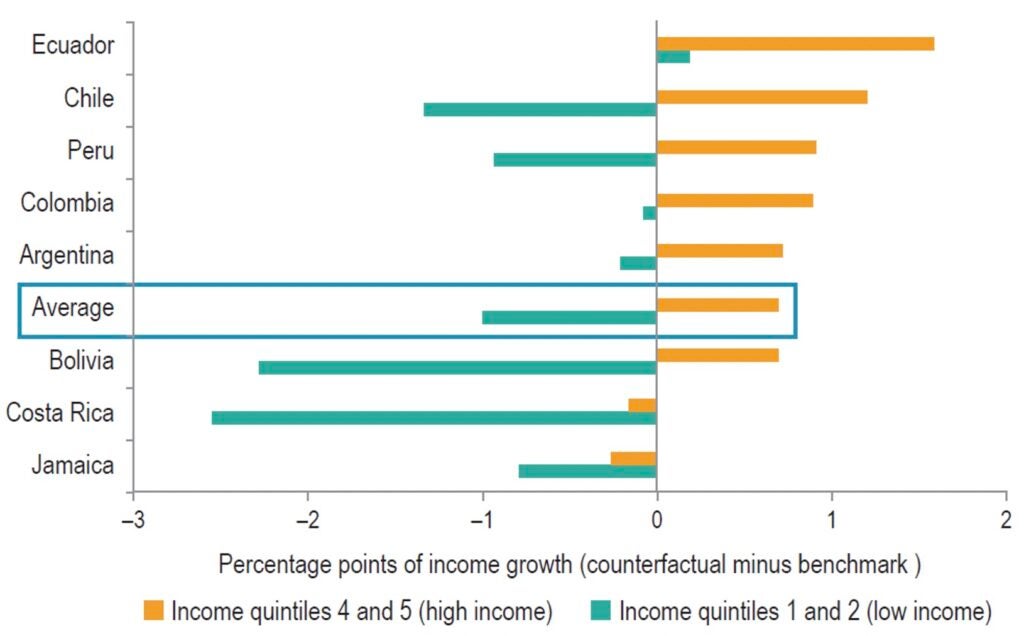

Consumers would be negatively impacted in the contrafactual scenario with margins because the prices paid would increase in comparison with the baseline scenario. But there are some nuances. The poorer households would see their real income decline by an average of one percentage point (Figure 2). For wealthier households, the impact is more complex. These households own a larger portion of the capital stock, and therefore they would simultaneously benefit from the higher profits generated by the margins. In six of the eight countries analyzed, the increase in profits as a result of the higher margins would be large enough to counteract the negative effects of higher consumer prices. As a result, the real income of those from a higher socioeconomic strata would increase in net terms by a little more than 0.5 percentage points. This means that the distributive impact of the margins is regressive. In other words, poorly-designed price regulation increases inequality.

Figure 2. Impact of Efficiency Gains on Household Income, with Margins between Prices and Costs

Note: The graph shows the cumulative change—in real income percentage points—of the contrafactual scenario (that is, greater efficiency with margins between prices and costs) minus the baseline scenario (that is, greater efficiency without margins between prices and costs) over the course of 10 years.

These results underscore the need for adequate regulation that balances incentives for service providers to seek and secure efficiency improvements with the need for the improvements to translate into lower prices for consumers. In the absence of this balance, efficiency improvements will not materialize, or their impact on the economy could be lower or even reversed. Our study From Structures to Services presents the actions that must be taken for the region to modernize its institutions and regulations. Investing more and better will be necessary; better regulation will be of the essence.

Leave a Reply