In responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, not all countries have implemented equally strict policies. While Spain and most countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have chosen to mandate lockdowns by law, including using security forces for monitoring, control, and coercion, in other countries—such as Sweden—decisions regarding confinement and social distancing have been left up to individual choice. While some countries use fines and arrest, others have appealed to a sense of shared individual responsibility. For example, the Swedish government has decided it is more appropriate to use nudges—the tools of behavioral economics—to remind people about the measures and means for reducing infection, declining to use obligatory quarantine measures. Through constant follow-up, the measures are adjusted daily based on evaluation of what works and what doesn’t.

Sweden’s measures can only be evaluated in the future and are based on two fundamental premises: high rates of interpersonal trust and a public sector with a well-developed capacity to react to new information.

- Interpersonal trust is essential for reducing infection when the risk varies by person. Young people have a much lower risk than older people or people who are immunocompromised. They can therefore handle a higher risk of infection. However, given that they could be asymptomatic transmitters of the virus, they can infect others who are at greater risk. For the low-risk population, the benefit of looking out for themselves hinges on other people doing the same. Thus, certain societies are able to maintain low infection rates without strict police enforcement only when individuals are able to trust that others are also properly following guidelines on social distancing and preventative measures.

- Countries with better government capacity have different public policy options for dealing with external shocks. Because they have robust public management tools, governments are able to avoid the inefficient costs of the more drastic measures. In fact, it has been shown that states with lower bureaucratic capacity respond with more rudimentary policies than states with higher capacity. The latter have access to a broader array of policies for responding to shocks, and are therefore able to mitigate the negative consequences with lower public expenditure commitments and greater room to maneuver. These lessons appear to also be applicable to this pandemic.

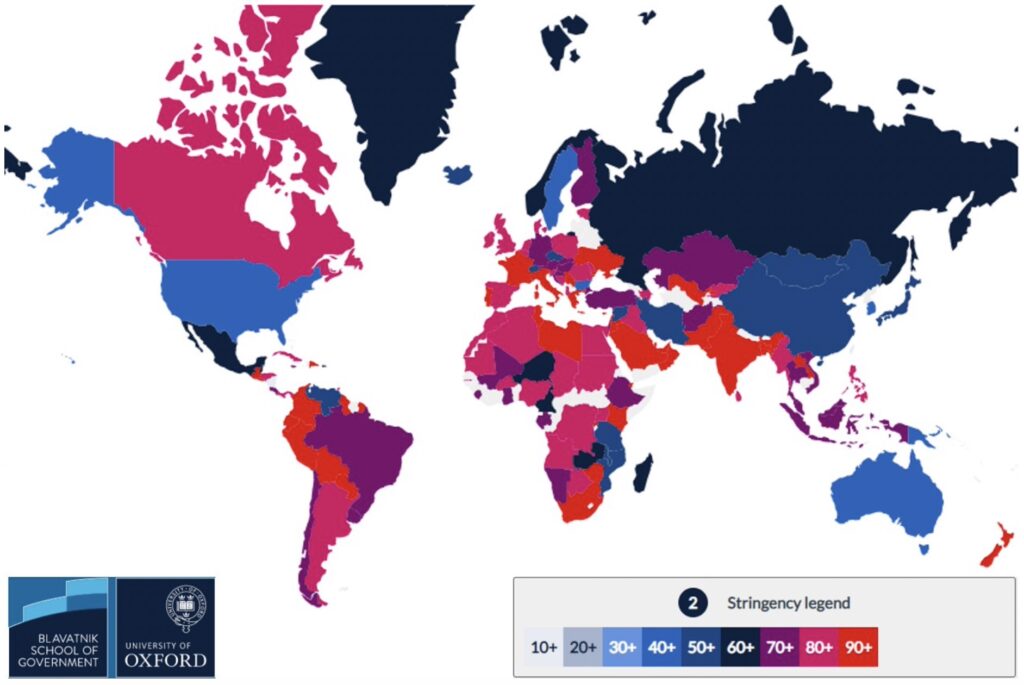

In order to evaluate how countries have reacted to this pandemic, Oxford University has prepared a stringency index that combines measures including social distancing and isolation ordered by governments to control and mitigate the spread of the virus. This global index includes indicators such as school closure, cancellation of public events, and mobility and travel restrictions, as well as economic policy and health measures. High scores indicate greater government restrictions and vertical control over the population. As can be observed from this map, countries vary widely in terms of the restrictions they have put in place (data through 25 April 2020).

Figure 1. Relationship between the Number of Covid-19 Cases and the Government Response

Source: Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker.

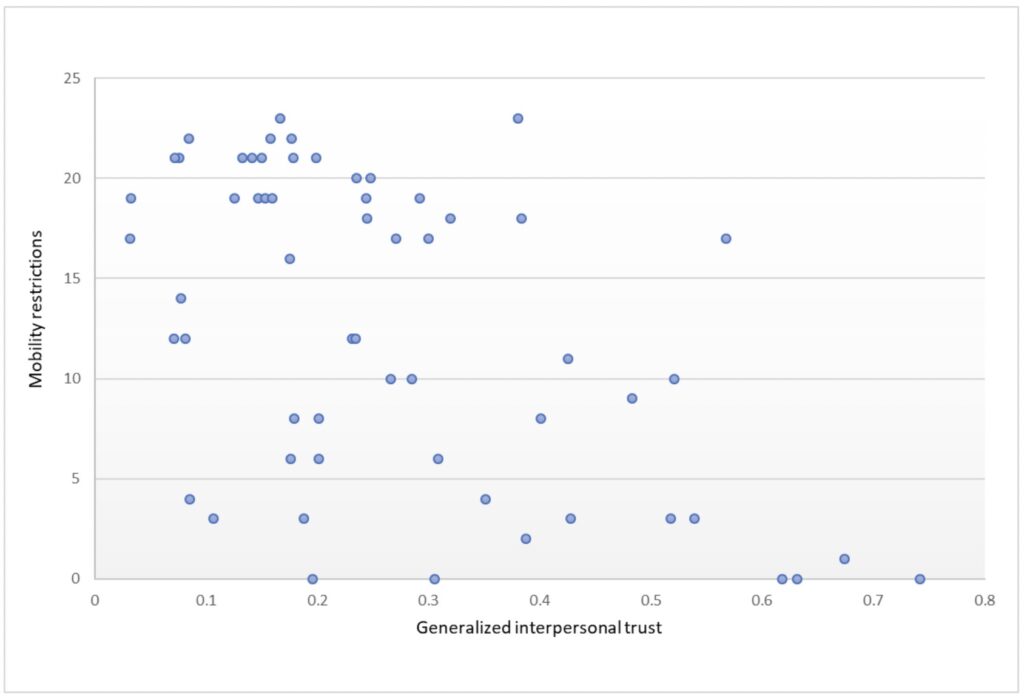

To put this data into context, first we built an index according to whether countries had decided to close schools, commerce, public events, or public transportation, as well as whether they had put restrictions on leaving the home or on domestic or international travel. We then combined this data on mobility restrictions with data on trust and government capacity to gauge its influence. Figure 2 shows the relationship between levels of interpersonal trust (horizontal axis, based on the latest World Value Survey data) and the strictness of mobility restrictions imposed by governments as of 100 confirmed cases of Covid-19 (vertical axis, based on Oxford data). Both indexes correlate negatively, which is to say that the countries putting greater restrictions on mobility are also the ones that tend to have lower interpersonal trust.

Figure 2. Mobility Restrictions and Trust

Source: Prepared by the authors using data from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker and the World Value Survey.

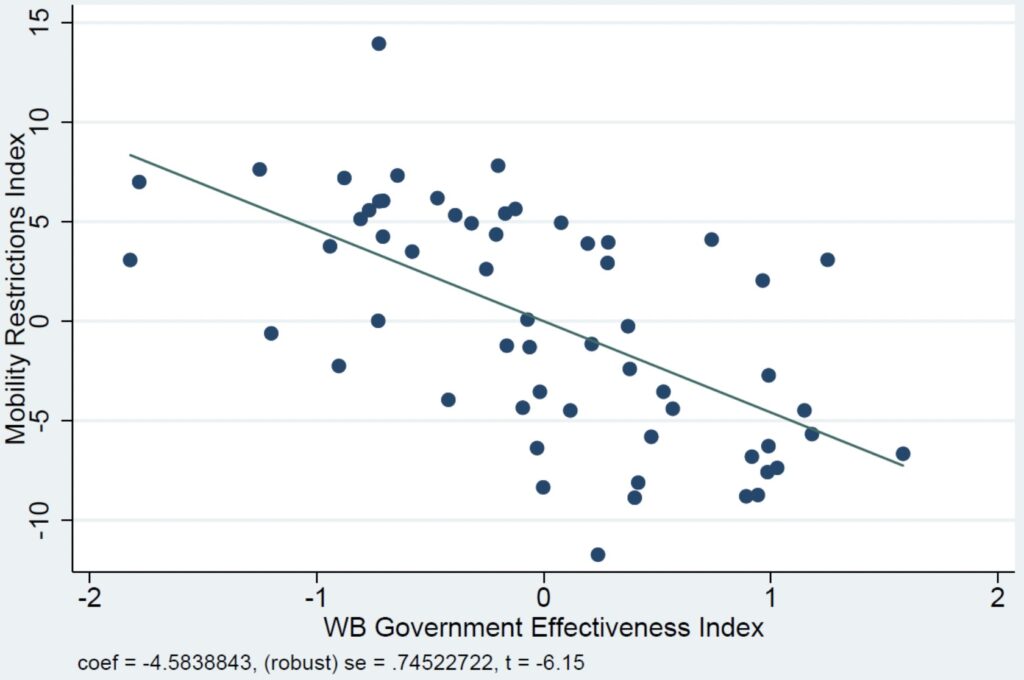

Does government capacity matter? To answer this question, we carried out a regression analysis. We took the latest values available from the World Bank government effectiveness index and from the World Value Survey’s interpersonal trust data and combined them with the number of deaths at the time when the first 100 cases were confirmed (we did the same for the first 1,000 cases and the results do not change). We also took into account the number of days from the start of the pandemic to control for the fact that by the time some countries saw their first infections, more was known about the virus’s impact.

As expected, as time passed since the beginning of the pandemic, countries began implementing more restrictive measures, even when the number of cases was still low. Trust also matters. In Figure 3, the vertical axis shows restrictions on mobility and the horizontal axis shows the government effectiveness index (the data are controlled for all the aforementioned variables). As can be observed, the countries whose governments have greater capacity need fewer mobility restrictions to contain the spread of the virus.

Figure 3. Partial Effect of Government Effectiveness

Source: Prepared by the authors using data from the World Bank’s Gov Data 360, the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, and the World Value Survey.

It is still too early to evaluate which countries have taken the best measures, or which have been too restrictive or not restrictive enough to stop the spread of the virus. Likewise, it is too early to assess which countries will be hit hardest by the pandemic’s negative consequences. What the evidence does appear to indicate, based on the empirical evidence we present here, is that the polices that governments have available to them vary depending on their capacities and on levels of trust in the population. Government capacity is the weak link in Latin America and the Caribbean, and thus most of the region’s countries have had to implement harsh restrictions, with significant police enforcement. Investment in government capacity will be fundamental following the pandemic. Governments can also increase citizen trust and help consolidate social cohesion; this pandemic is an opportunity to do so.

Leave a Reply