As the COVID-19 pandemic faded in 2021, markets expressed optimism in the worldwide economic outlook and capital flows to emerging markets recovered. It was not to last. The central banks of developed economies are now mopping up the abundant liquidity they had in place since the Great Financial Crisis to fight inflation in their own countries. Geopolitical risks in 2022 have risen and international economic uncertainty has surged. Amid these transformations, capital flows are becoming ever more volatile in emerging markets as investors look for safer positions.

Capital flows to Latin America and the Caribbean are especially at risk. After coming under pressure for most of 2022, their immediate future looks shaky, demanding sound economic fundamentals from governments of the region and a potentially greater role for multilateral banks in allowing external funding and preventing economic turmoil.

Investment Flows from the US

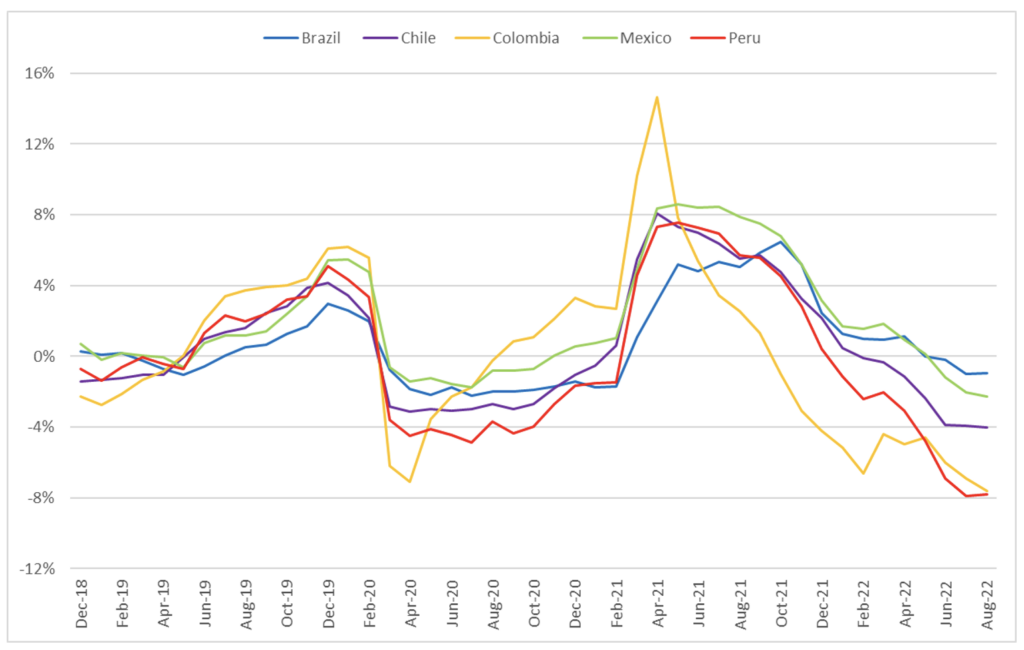

One of the timeliest data sources for foreign portfolio investment comes from Emerging Portfolio Fund Research (EPFR), a private company that tracks equity and bond purchases and investment flows from pension and mutual funds in the US. Depicted in Figure 1, EPFR inflows started to recede in five of the largest economies of Latin America and the Caribbean around October 2021. After the start of the Russia-Ukraine war, the 12-month cumulative flow became negative. In other words, the funds had taken money out of these countries just as the countries’ financial needs increased. These flows are volatile, but they show a consistent trend across the region. As of August 2022, the exodus of capital from the region is similar to that in the second quarter of 2020, the height of the pandemic.

Figure 1. EPFR Yearly Flows

Note: The figure exhibits 12 month-cumulative flows as a percentage of the total asset allocation for each country. This allows to control for the size of the portfolio market versus the amount of traded flows.

Decreasing equity flows indicate that foreign investors are reducing their positions in stocks publicly traded in those five economies, suggesting a weak outlook for economic activity. Bond purchases by foreigners are also falling, indicating a rising likelihood of government debt distress. On aggregate, less foreign investment means less financing resources available for the region.

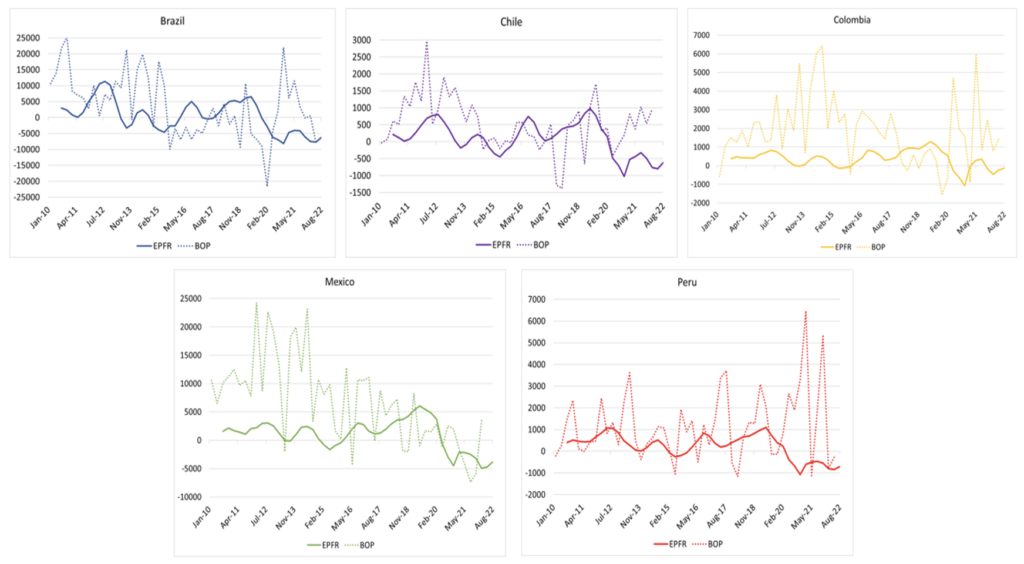

EPFR only covers a small subset of a country’s external financiers, but they are a leading indicator of the aggregate financial flow. Figure 2 shows a panel with five Latin American economies described above. In each country panel, the portfolio investment inflows from the balance of payments statistics (dotted line) seem to move around the quarterly flows from EPFR (solid line). In all cases, the timelier EPFR data points toward a persistent reduction in foreign capital flows in the second and third quarter of 2022, tightening the financial conditions for the region.

Figure 2. Quarterly Portfolio Investment Flows by Foreigners to Five Countries of the Region

Quarterly portfolio flows from BOPS in LAC-6

The Risk of a Sudden Stop

A contraction in the financing flows present in the balance of payments statistics could cause a sudden stop. This occurs when foreign financing available to borrower countries suddenly dries up, leading to an abrupt financial account reversal. Sudden stops are particularly costly because the macroeconomic correction is driven by a sharp contraction of imports, which is only possible through a strong reduction in consumption and a recession, as explained in this study. The region now must deal with this heightened vulnerability of its external accounts, and that could deteriorate more given the challenges of the economic landscape.

Several downside risks from the current international environment could make things even worse for Latin America and the Caribbean. Inflation is at historic highs worldwide due to geopolitical tensions, uncertainty, and persistent global supply chain disruptions. Monetary policy has tightened sharply so far in 2022, and more action from central banks is expected, especially in the United States and Europe, fueling the possibility of a global recession. In these highly charged circumstances, capital outflows in Latin America are linked to flight-to-quality dynamics. Investors, in other words, are looking for safer locations offering higher returns.

Latin America and the Caribbean could be especially susceptible to the expectations of global monetary policy normalization and a weakening perception of the region’s prospects if a recession materializes. That is because of the region’s strong dependence on the price cycles of international commodities and the advanced economies’ demand for the goods it produces.

On the domestic front, downside risks are associated with a vulnerable macroeconomic outlook that still has not recovered completely from the pandemic. Although countries grew at rapid rates in 2021, fiscal and monetary policy still need to consolidate. Public debt remains at high levels, and fiscal deficits have not completely corrected. This might affect investors’ risk perception and increase the cost of credit in the future, further limiting the availability of foreign financial resources. Monetary policy is responding to higher inflation at different speeds among the region’s economies. It still, however, needs to catch up with the global stance to partially compensate the returns investors are receiving internationally.

The Need for Action in Latin America and the Caribbean

To mitigate those risks, Latin American and the Caribbean economies need to strengthen their positions. As shown in this study, sound economic fundamentals allowed several vulnerable countries of the region to avoid sudden stops during the pandemic by guaranteeing access to international financial markets. The role of multilateral banks was also critical and is becoming even more relevant, given their ability to provide credit at lower costs during times of low global liquidity and economic turmoil.

Leave a Reply