Does greater spending on education boost learning? Educators and policymakers worldwide have debated that question for years. When it comes to Latin America and the Caribbean, however, one thing seems clear: Money may help; it may even be crucial, but it is never enough.

Latin American and Caribbean governments have made immense efforts to increase spending, dedicating on average 3 percentage points more of their GDP to education than they did 25 years ago. Indeed, at well over 5% of GDP, governments in the region spend roughly as much as the United States and the other countries of the OECD and considerably more than countries with similar levels of economic development.

Poor test scores despite the money spent

But something is not working. Poor educational outcomes, related to poor educational systems, have left the region sorely lagging in the global economy’s race for better skills. In our recent flagship report Learning Better: Public Policy for Skills Development, we compared results on different tests and found that fewer than half of the students in the region would have scored above the minimum standard had they participated in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMMS), a global assessment of fourth graders. That compares to 95% of fourth grade students in the United States and 66% in countries with similar levels of gross enrollment and development. By the same token, on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) for 15 year olds, the 10 nations in the region that took the test were on average 2.5 years of schooling behind the average for the OECD. Sixty-three percent of Latin Americans were unable to conduct more than the simplest math tasks for their grade.

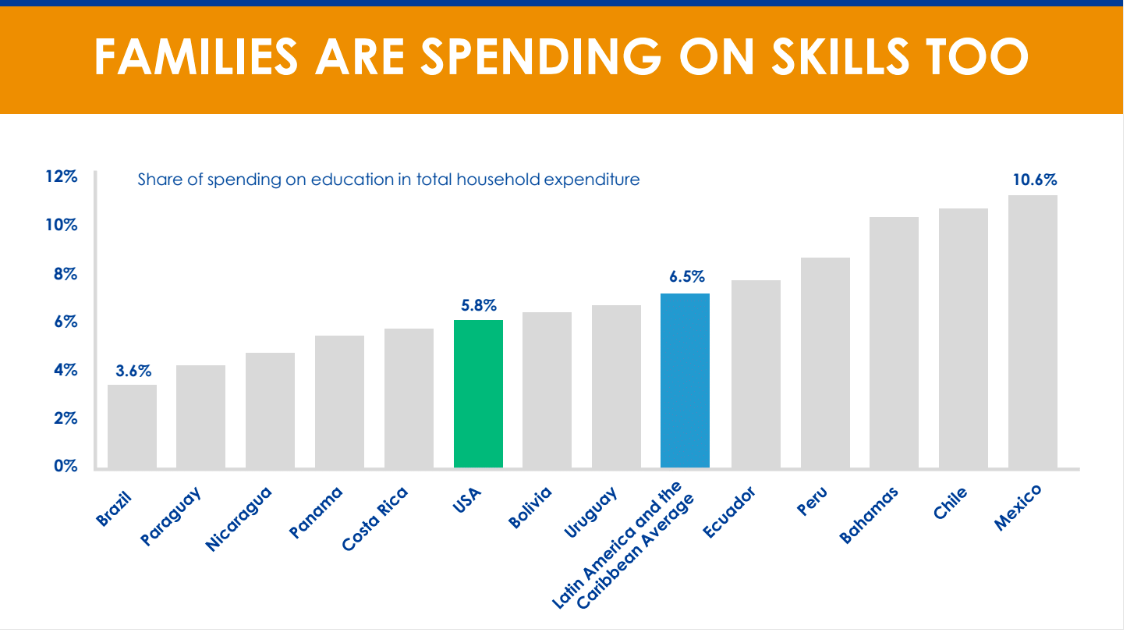

If these results are dismal, private spending doesn’t seem to be closing the gap. The average household in Latin America and the Caribbean spends 6.5% of its budget on skill-related expenses. That is more than in the United States where the average household spends about 5.8%.

This use of private resources by and large is not going for tutoring. Instead, Latin Americans opt out of public education as soon as they enter the middle class. The proportion of students that attend private primary and secondary schools in the region is about 22 percent, compared to 8 percent in the United States. Thus, households in the region are likely spending their money to compensate for either the lack of access to or the lower quality of public schools. By contrast, in the United States private spending complements public spending.

The wealthy vastly outspend the poor in skills development

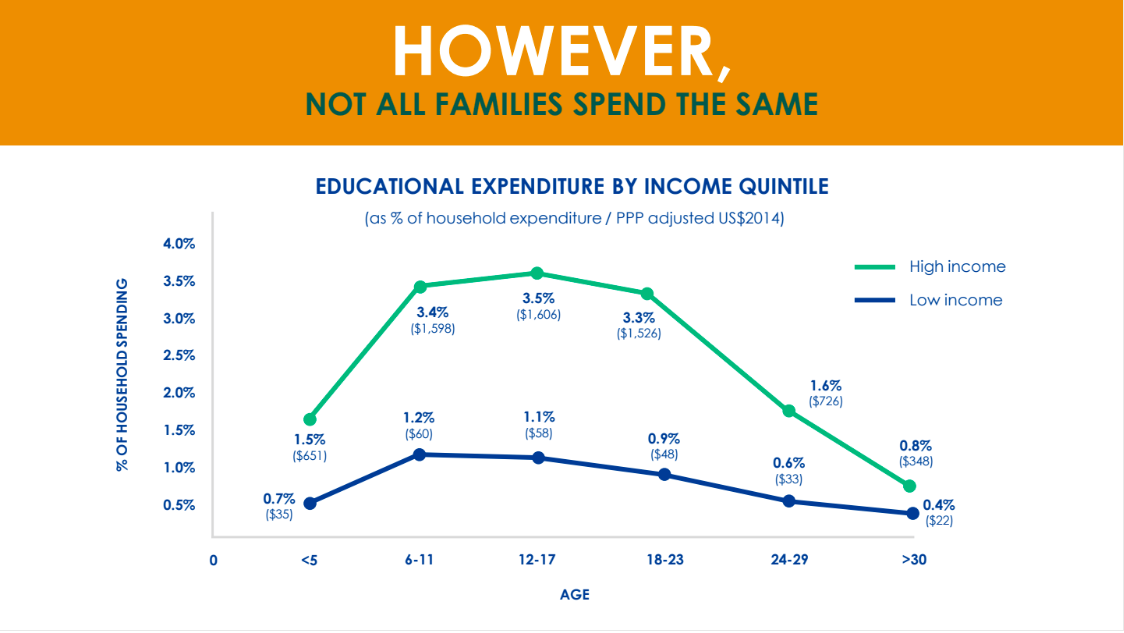

Investment on skills development vary substantially by socio-economic status. High-income households with very young children tend to spend twice as much of their budget on skills development as low-income households. These gaps widen during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood when children and youth attend school and persist as they enter adulthood. Moreover, the gaps magnify if measured in absolute value because total expenditure is much higher for households at the top of the expenditure distribution. A household in the fifth quintile of the income distribution in Latin America and the Caribbean spends three times more on skills development than a household in the fourth quintile and 10 times more than a household in the first quintile.

That is a huge difference. Still the wealthy are not advancing as they should. High-performing kids in the region still underperform high-performing kids in the developed world by a large margin. And that is because private schools in Latin America and the Caribbean on the whole are not particularly good. Kids in private schools may do better academically than those in public schools because they have fewer behavioral problems and more support at home. But teachers in private schools are not necessarily better than in public ones.

Many recommendations in our flagship report are dedicated to how public education can be improved from pre-school through secondary and adult learning. But improving education is a dynamic process. Crucial to the effort is the use of the scientific method, including the use of pilot projects and rigorous evaluations, to determine which interventions work and which don’t.

Increasing investments in early childhood learning

Spending wisely is paramount. The share of public spending allocated to early childhood is about a quarter of the spending allocated to childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The efficiency of this allocation is questionable. If there are strong self-productivity effects (i.e., if skills beget skills), then the marginal returns of investing in early childhood would likely be higher than the returns of investing later in life.

Reallocating resources, of course, is not enough. The region needs to spend better in the support of skills development at every age, and there is no reason not to do so: there is mounting evidence that some policy options are much more cost-effective than others.

Latin America and the Caribbean is at a crossroads where vastly improved skills will be needed to increase productivity, reduce poverty, and adjust to a technological revolution that is demanding ever more nimble and capable minds. The region’s dedication of essential resources demonstrates that governments are aware of this challenge. But money will only take them so far as long as money is not invested more wisely on better educational interventions.

Leave a Reply