The response to the coronavirus crisis has revealed the shortage of personal protective equipment and critical medical devices. According to the WHO, the worldwide capacity to supply needed items through traditional suppliers is under stress. To produce and provide supplies directly in the service of local first responders, maker communities across Latin America, the Caribbean, and around the world have mobilized to share open source designs and pool their production capacity in the midst of an extremely environment complex. This has involved working around obstacles such as restricted movement and limited materials, unestablished rules and procedures, and constant iteration of designs to ensure the pieces produced are sufficiently effective enough to provide real support.

While they do not provide a complete solution, these collective efforts demonstrate both the role and value of applying open knowledge and collaboration to the pandemic response in an exceptionally tangible way. In this article, we explore what is currently being learned from different interventions by makers in Latin America and the open resources being shared.

Collaboration in response to COVID-19 from the open and maker communities

The maker movement is quite active and diverse in Latin America. The website CoronavirusMakers highlights maker groups mobilized against COVID-19 in at least 13 countries in the region. Whether they are working from institutional labs or independent workshops, many of these communities have responded in solidarity to expand their local capacities by producing supplies through the use of digital manufacturing technologies such as 3D printing, laser cutters, and open hardware.

In the context of the current pandemic, 3D design plans have been opened for all types of devices. Since the start of the crisis, one of the key learnings that has emerged from the wider global maker community is what types of devices are best suited for makers to safely contribute to the response based on their level of expertise and available materials. For example, personal protective equipment items such as masks, face shields, and gowns, are relatively simple to manufacture and, at the same time, provide very immediate value to healthcare workers on the front lines.

In contrast, medical devices like ventilators require multiple sophisticated components and a higher level of durability to be safe and functional. To illustrate this point, in Medellín, the InnspiraMed team is working to develop an effective and low-cost open-source ventilator system, in a professional laboratory with more than 56 highly trained engineers and scientists. Their advances are very inspiring given the opportunity to disseminate open-source solutions. This accessibility is critical given the extreme scarcity of this equipment worldwide compared to the increased demand, raising the call for multiple creative solutions. At the same time, it demonstrates the deep technical complexity of these instruments and is therefore not a realistic option for most makers who are voluntarily engaging their efforts to the response.

The face shield: an open-source design from Europe reused in Latin America and beyond

These factors have contributed to making the face shield, or face protector as it is also called, a popular choice for makers everywhere.

Fans of 3D printing will surely recognize the name Prusa printers. The Czech brand claims manufacturing the world’s most popular open-source 3D printer. On March 18, Prusa announced a deal to donate 10,000 units of their face shield to the Czech Ministry of Health, after running through a dozen prototypes and two rounds of verification. This first design, known as “RC1”, was quickly released in open source, “to get this to as many people who need it as soon as possible, around the world”, with the promise to deliver additional updates as the design was iterated and improved with use. They have now reached version RC3, with the incorporation of improvements, learnings, and other measures thanks to worldwide collaboration.

We identified three different experiences related to the production of face protectors based on this design in Argentina, Costa Rica and Peru:

“Together, we make it” : connecting makers, medical personnel and materials in Peru

Jorge Alfredo Field Montenegro, a Peruvian maker and general manager of La Fábrica 3D in Lima, Peru, was interested in mobilizing in support of the local response to the COVID-19 emergency. He began to collaborate with the National Center for the Supply of Strategic Health Resources (CENARES) of the Peruvian Ministry of Health. Upon defining the agreement, everyone realized the uniqueness of the situation: there simply was no guideline or precedent for how to receive 3D-printed materials. The fact that the initial Prusa design had been developed in close collaboration with another ministry of health was considered a relevant technical basis. La Fábrica 3D is in the process of producing 500 face shields to donate to CENARES, to be distributed through the Peruvian Society of Doctors for Emergencies and Disasters (SPMED). The first delivery of 130 3D-printed face shields was made on March 21 at the Casimiro Ulloa Hospital in Lima.

Field is part of BackUpMakers, a network of makers and fab-labs across Peru. The initiative, founded by Isaac Malca Ruiz, co-creator of the app TuRuta, and Carlos Terranova Veliz, an industrial designer, seeks connect all people and printers across the country, with the intent to coordinate better among their volunteers. In effect, they are also mapping the national 3D-printing production capacity and access to digital manufacturing equipment. As the coronavirus reached Peru, the community began to organize more, in order to manage and channel all of the interest and efforts being manifested by the community to support the response, in the capital and beyond.

The network has other projects that support this vision. Malca and his team volunteered to create the website MiHospitalNecesita in order to continue detecting opportunities to deliver supplies, especially in the most remote areas. Terranova told us about the need to adapt the design released by Prusa to a low-cost version, with more accessible materials. Reflecting on his experiences living in cities outside the Peruvian capital such as Chiclayo and Tumbes, he said that modifying the design instructions to leverage materials such as cardboard and laser cutters would mean that more people could recreate the face protectors from their homes. The first version of the design and the steps to make the face shield are published online in the BackUpMakers repository.

Coronathon: a marathon of agile and circular mass production in Argentina

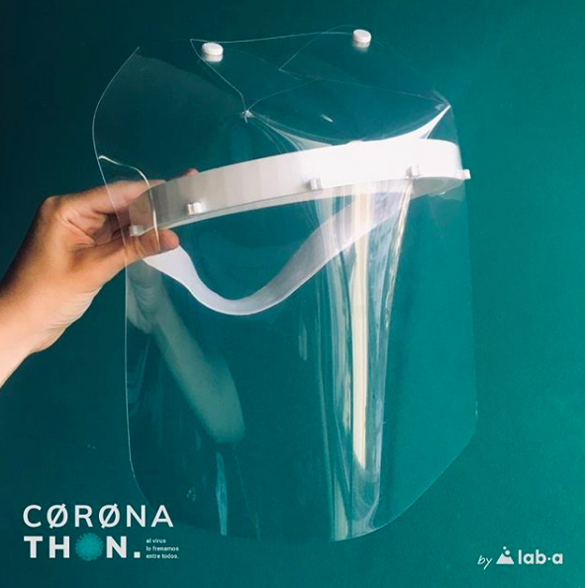

In Buenos Aires, the same Prusa design has been reused, adapted and manufactured in record time using a massive collaboration methodology organized by Lab.A, a company whose objective is “to use technology to reduce barriers experienced by people living with disabilities.” On March 22, Lab.A announced on Instagram their collaboration with health professionals to manufacture facial protectors and distribute them to health service providers around the City of Buenos Aires. They asked the public for additional support, to meet “the enormous demand.” The results achieved in a single day was astonishing. They identified 600 ready-to-enlist printers and linked them to a network of producers throughout the city and surrounding areas. They received inquiries from some 50 health centers and orders for more than 5,000 face shields. “What started as an initiative from inside our company has transformed into a gigantic community of people who […] want to contribute,” announced Facundo Cancino, the founder of Lab.A, again on Instagram. “So, let’s give it a name: Coronathon.”

Julián Morelli, one of the engineers from the Lab.A team, shared more information about the experience. Based on the response Lab.A. received to the initial call, the first coordination meeting was organized that same day to define different workflows and circuits. The Argentine 3D Printing Chamber joined efforts to coordinate the first production goal of 10,000 pieces. A channel was also organized for those who wanted to make donations, estimating a cost per mask of $ 100-150 Argentine pesos (1.50-2.30 USD). To date, they have met their production goal of more than 10,000 facial protectors and have more than 1,850 units delivered, 35 health centers assisted and more than $ 2,400,000 Argentine pesos (37,000 USD) collected in donations.

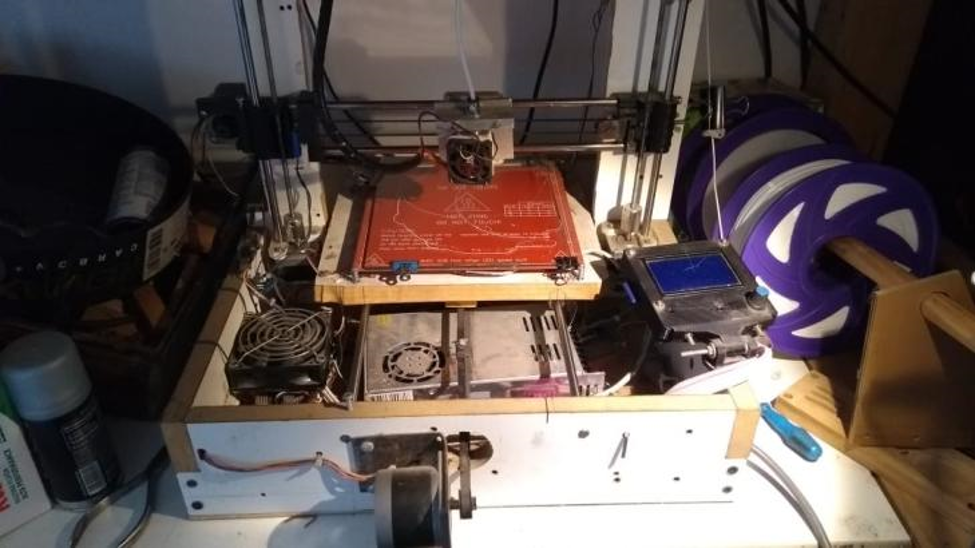

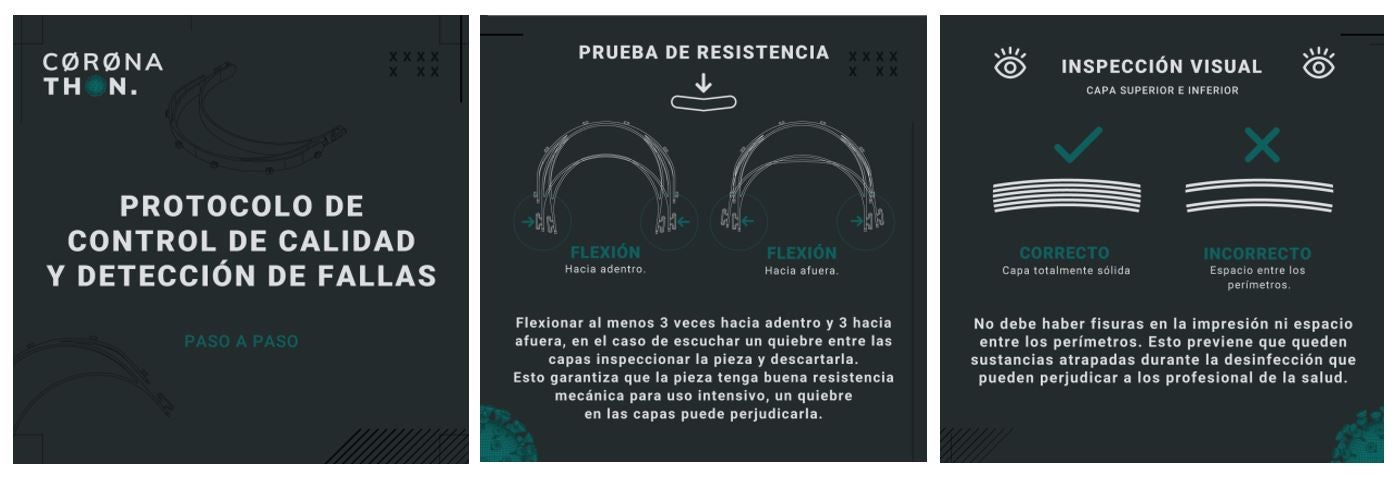

The massive scale of the project required organizing with agile methodologies and constant coordination through a collaboration platform. They are using Discord. Each participant can access the designs, the asepsis protocols, the means of assembly and other necessary resources and can also contribute by responding to questions or contributing ideas. The community starting grouping into conversations based around the different printer models being used (Prusa-mk2-mk3, Anet-a8, Ender-3, Creality-cr-10) and sharing tips to improve the printing experience, even trouble-shooting for those working with homemade machines. Like Gustavo Sacchi, a participant who was experiencing difficulties with the size of the headband, because the printer bed was touching the edges of the structure he had built. After several exchanges, he opted to saw some parts and continue printing.

All the efforts and learning of these intense production days have been complemented and amplified via permanent contact with healthcare professionals. They guided the elaboration and compliance with the asepsis protocol along the different stages of the supply chain and have helped to identify the health centers where the supplies are needed.

A final noteworthy aspect of this initiative is the effort to evaluate the ecological impact of this campaign. In one consideration, improvements were made to the design to be printed: the height of the headband was minimized to optimize printing time and the plastic consumed. These modifications reduced the printing time from an average total of 2:40 hours to 2:11 hours per unit and the total plastic used per unit from 53 grams to 40 grams; savings which imply a greater impact when considering the scale of production. As another measure, they have partnered with Vuelta de Tuerca, a sustainable design venture, with the objective of recycling the waste plastic that is generated. Different logistics companies have joined forces to collaborate in the delivery of the face shields and the collection of the used materials to be recycled.

Printing with biodegradable material in Costa Rica

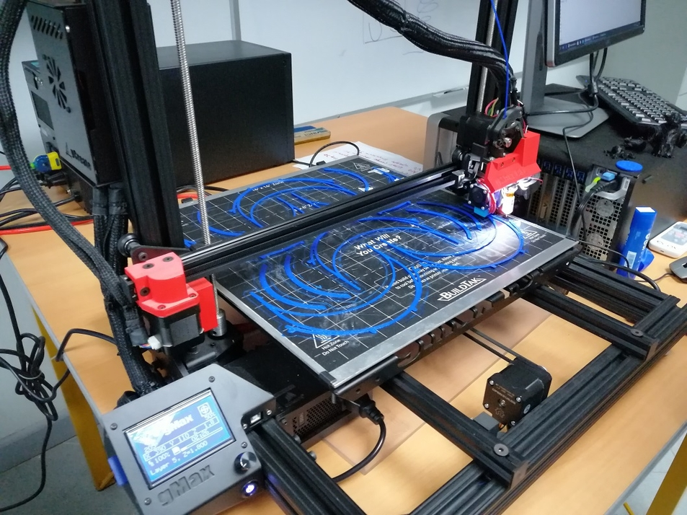

Other initiatives in the region have also considered how to make the manufacturing of these supplies more environmentally responsible. In San José, a team of engineers from the University of Costa Rica has also endeavored to produce face shields, using the same Prusa design (version RC3) seen in the previous cases. The dean of the School of Engineering, Professor Orlando Arrieta, provided additional information about their efforts.

The material used by the laboratory’s 3D printers is PLA, the abbreviation for Polylactic Acid. It is a biodegradable material, the base materials of which can be obtained from fermented plant starch such as that from corn, cassava, sugarcane or sugar beets. It is widely used in 3D printing and is sold by various suppliers in different formats for printers. “Depending on the printing characteristics, it offers good stiffness for printing the parts,” Arrieta said.

The face shields are assembled with the 3D-printed pieces, a transparent acetate screen and an elastic for fastening to the head. The approximate cost in materials is around 3.5-4 USD per unit.

Transforming collaborative efforts into sustainable partnerships and integrating with transparent supply chains

There are dozens more stories like these taking place across Latin American and the Caribbean, demonstrating the commitment of these makers to their communities. All of these cases demonstrate the level of energy, ingenuity and creative capacity that exists around the region. As the pandemic continues toward its peak around the world and changes our collective understanding of the status quo, many questions remain. How many more supplies are needed to close the gap? How can the public and private sector incorporate these efforts in a transparent and accountable way in the long term? Will strengthened local ecosystems emerge alongside these global knowledge-sharing networks for other products and services?

These questions are an opportunity to consider a more ample integration of open knowledge, collaborative methods and circular systems, not only in the response to COVID-19, but also in other development challenges facing the region.

By Michelle Marshall, Laura Paonessa and Jesenia Rodriguez, consultants to the Knowledge and Learning Division at the IDB

Keep reading:

- Coronavirus: ¿Cómo apoyar desde el sector de fomento a la innovación y las pymes?

- ¿Qué es un maker space?

- Introducción a la fabricación digital

- Cómo crear un FabLab en tu centro

Leave a Reply