From Wuhan to Italy, one of the most serious problems associated with COVID-19 has been the lack of intensive care units (ICUs), mechanical ventilators, and staff trained to operate them. In both cases (and notwithstanding China’s astonishing expansion of hospital capacity), many of the deaths could have been prevented with more ICUs and more ventilators. In the absence of this, doctors are using triage—a process implemented in an emergency for selecting and classifying patients—to decide who gets an ICU bed and who doesn’t; who receives a ventilator and who doesn’t; who survives and who doesn’t. Accounts from Italian doctors, like the ones in this New York Times podcast, are extremely distressing.

If nothing is done, New York City is headed toward the same problem. The governor and the mayor are constantly taking to television to ask for help. A hospital ship has been sent, and there’s talk of using the Army Corps of Engineers and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to quickly build up new hospital capacity.

But what should be done about ventilators, which can be the difference between life and death for the gravely ill?

Import them? Impossible: Demand is enormous, and all countries need them. Many countries are even blocking ventilator exports, holding onto them to meet their own needs.

Produce them in existing factories? The factories are already producing at full capacity. Increasing production is possible but not easy, as this recent article describes. The most sophisticated ventilators are complex machines controlled by computers. They cost as much as $50,000 each and contain hundreds of parts produced all over the world.

Last week, President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act, which is generally used in times of war. The aim is to increase production of the inputs needed to handle the crisis, including ventilators. The United Kingdom has asked Rolls-Royce and Jaguar to produce ventilators, and companies like Ford, General Motors, and Tesla will follow suit in the United States, given the drop in demand for automobiles. But these efforts are at a very early stage, and there is no guarantee that the ventilators will be available when they are needed.

So what should be done? Before getting into the idea we would like to suggest, we should look at the geography of the hospital capacity shortfall.

The Geography of the Hospital Capacity Shortfall

A recent report from the Harvard Global Health Institute provides a snapshot of the shortfall in hospital capacity for virus response. The report assesses installed capacity in each of the 306 “hospital markets” in the United States (called Hospital Referral Regions, or HRR) in terms of beds and ICU beds. Using information on the adult population and the population of people over the age of 65, they simulate demand for beds at different levels of infection for the adult population (20%, 40%, and 60%) over different timeframes (6, 12, and 18 months) The greater the number of people infected and the shorter the timeframe, the greater the pressure on the hospital system.

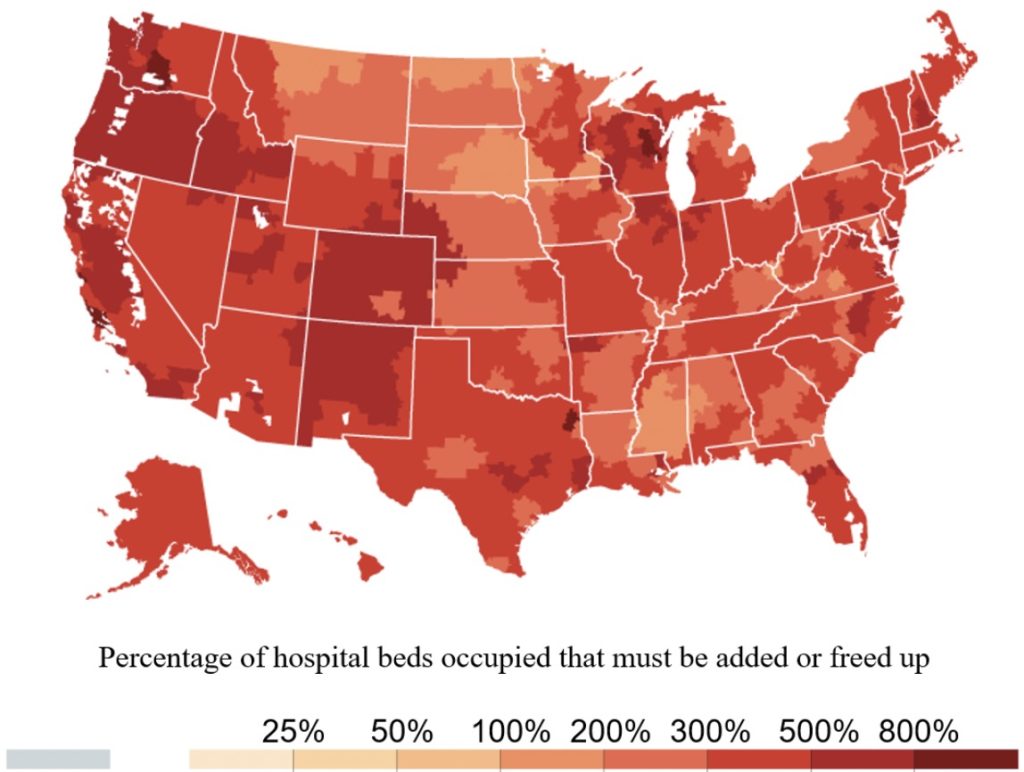

In the worst-case scenario (60% infection in 6 months), all hospital markets are overwhelmed—some more than others.

Estimates of Hospital Bed Capacity with 60% of Adults Infected with COVID-19 over 6 Months

Source: New York Times, based on Harvard Global Health Institute data. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/17/upshot/hospital-bed-shortages-coronavirus.html

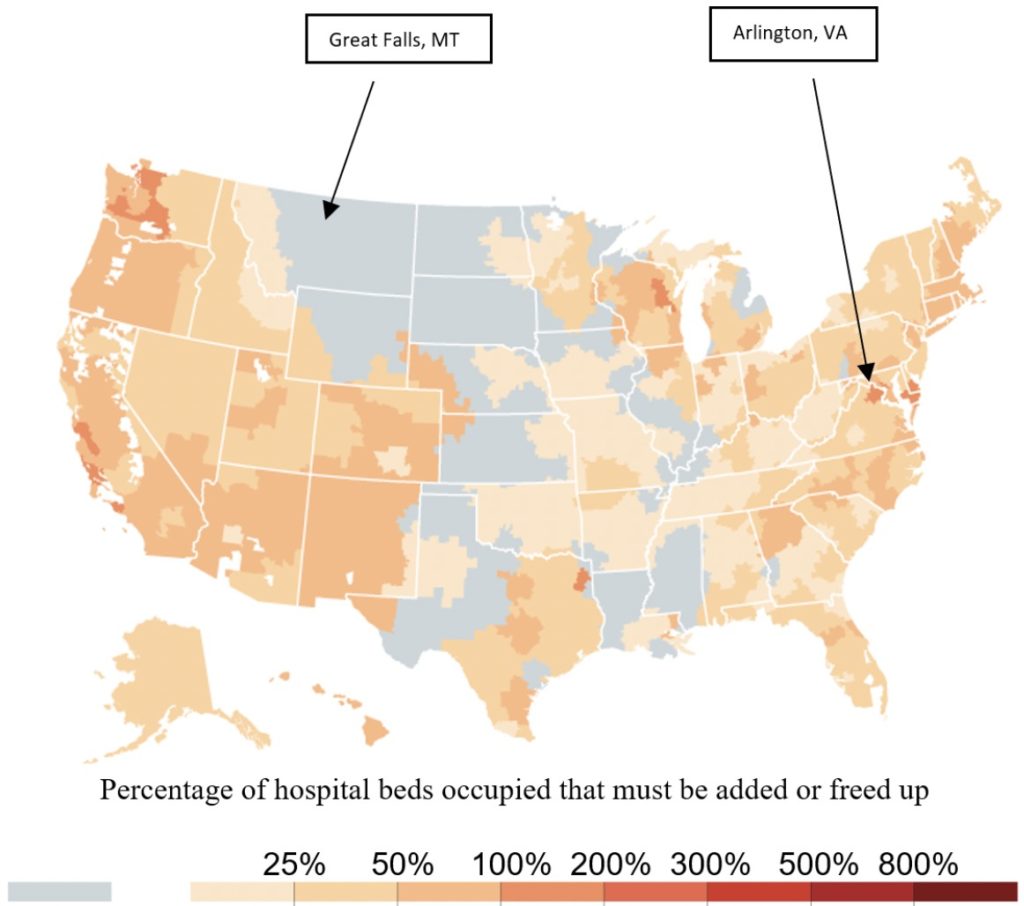

What happens in a more moderate case? The following figure shows the case of 40% of adults infected within a timeframe of 18 months. Some hospital markets—like in Arlington Virginia—would be overwhelmed. However, others—like in Great Falls, Montana—would be operating below capacity.

Estimates of Hospital Bed Capacity with 40% of Adults Infected with COVID-19 over 18 Months

Source: New York Times, based on Harvard Global Health Institute data. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/17/upshot/hospital-bed-shortages-coronavirus.html

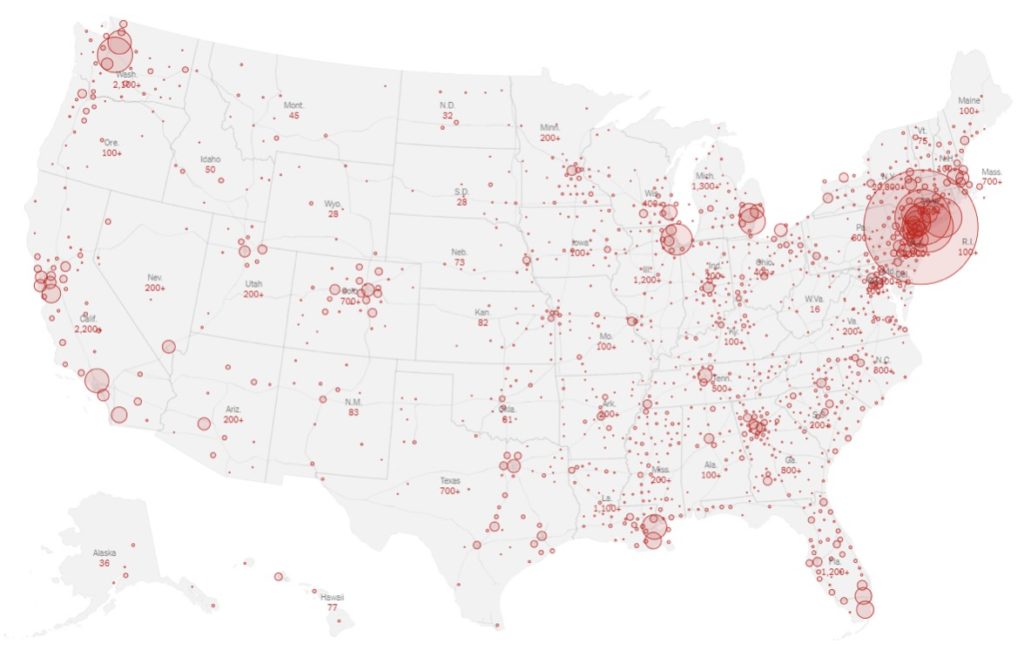

Harvard’s simulations assume that the percentage of people infected is the same in all markets. However, we know that is not the case. This map from the New York Times shows the distribution of reported cases by state and county (as of March 23).

Source: New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html

A Sharing Economy Solution

Clearly New York, with its 20,800 reported cases, is already under pressure. However, if the distribution of ventilators is similar to that of beds, Montana, with 45 cases reported, would have extra ventilators. Why not share them? Montana and other states with few cases could lend—or even rent—these ventilators to New York so it could respond rapidly to the crisis, at least until the cavalry—led by the automakers—arrives. The staff trained to operate them could also be temporarily transferred (with the applicable compensation). Once the crisis is over, New York could return them.

These types of collaborations between jurisdictions already take place in other areas. For example, cooperation on fire control between fire departments in different states is already extensive. They share personnel and equipment knowing that they will receive reciprocal support in the future should they need it. This type of aid also takes place internationally, as shown by this recent New Yorker article on North American firefighters helping with the fires in Australia.

But fires do not tend to take place at the same time. What happens if the virus is worse than expected and Montana needs the ventilators back? Can it trust New York to return them in the middle of a health crisis? Not necessarily. What we have here is a commitment problem. If New York’s promise to return them when Montana needs them is not credible, Montana will sit on its ventilators and not share them. And for good reason!

Because of this commitment problem, the market for loaning or leasing ventilators disappears, and each hospital will be limited to its own stock, with some federal help using its (limited) strategic reserves.

How can we solve this problem? What is missing is an enforcement mechanism. If the federal government could credibly commit to enforcing the promise to return the ventilators when they are needed, this “market” could be created, saving many lives. Enforcement by the federal government could be particularly complicated in countries with federal and decentralized systems like the United States, as well as Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina. But if these challenges could be overcome, New Yorkers will be very grateful. Overproduction of ventilators—which will not be needed after the crisis—could be avoided. Meanwhile, other countries—some of them in our region—could learn from the example.

I had no idea that the lack of intensive care units, mechanical ventilators, and staff trained to operate them has been one of the most serious problems associated with COVID-19. Apparently, when I found out that my cousin has tested positive for corona virus, we rushed him to the hospital but sadly I noticed that equipments for this pandemic are not enough. With that, I’d like to encourage everyone to donate ventilator use for patients diagnosed with COVID-19.