This week, researchers at Imperial College published an extremely important article. It presents an epidemiological model and evaluates interventions for reducing contact between people to slow the transmission of the novel coronavirus and the disease it causes, COVID-19. The model, applied to the United Kingdom and to the United States, analyzes effects on the number of dead and on demand for beds in intensive care units. The results are surprising and relevant to Latin America and the Caribbean, and they allow us to outline a strategy for fighting the virus.

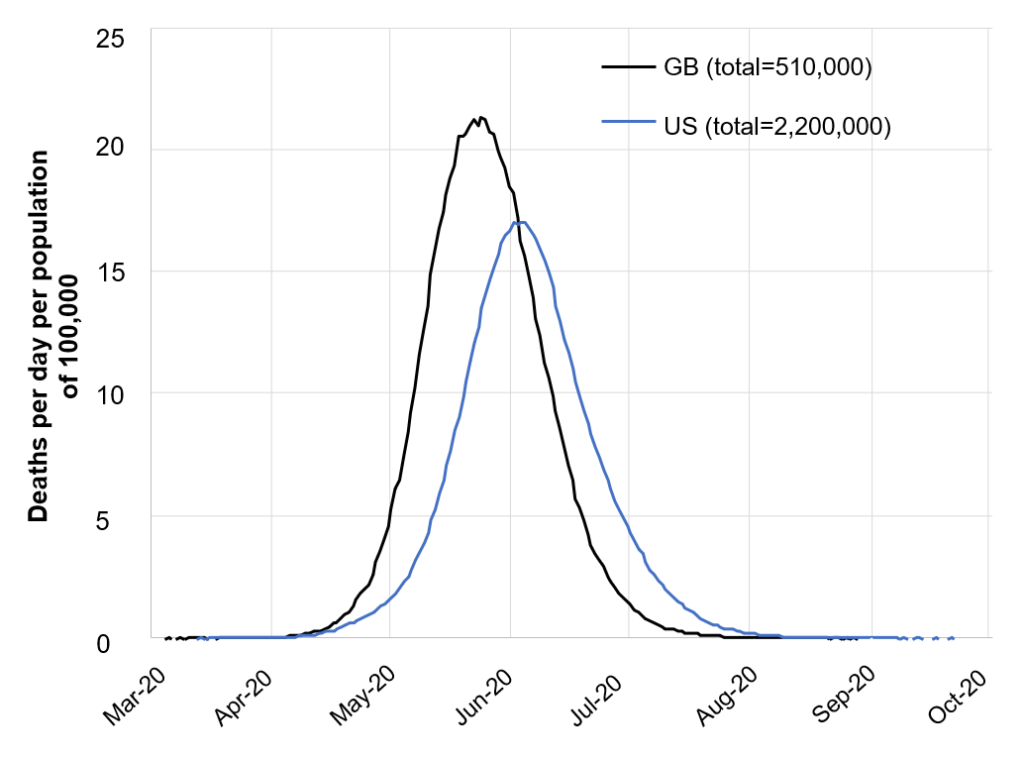

Before evaluating the public policies that different countries are using to face this crisis—quarantines, closing schools and universities, social distancing—the study looks at the consequences of doing nothing. They are terrifying. In the United Kingdom, more than half a million people would die. In the US, the number would reach 2.2 million. Hospitals would be absolutely overwhelmed. The United Kingdom has 8 critical care beds per 100,000 inhabitants. In the case of doing nothing about the virus, it would need 280!

Figure 1. The Consequences of Doing Nothing

Source: Ferguson et al. (2020).

The policies evaluated are the following:

- Isolation of symptomatic cases at home for seven days, reducing external contact by 75%, maintaining household contact. Assumes 70% compliance.

- Voluntary home quarantine: All members of households with a symptomatic case remain at home for 14 days, doubling household contact rates, but reducing contact in the community by 75%. Assumes 50% compliance.

- Social distancing of those over 70 years of age: Reduce contacts by 50% in workplaces, increase household contacts by 25% and reduce other contacts by 75%. Assumes 75% compliance.

- Social distancing of the entire population: All households reduce contact outside household, school or workplace by 75%. School contact rates unchanged, workplace contact rates reduced by 25%. Household contact rates are assumed to increase by 25%.

- Closure of schools and universities: Closure of all schools, but 25% of universities remain open. Household contact rates for student families increase by 50% during closure. Contacts in the community increase by 25%.

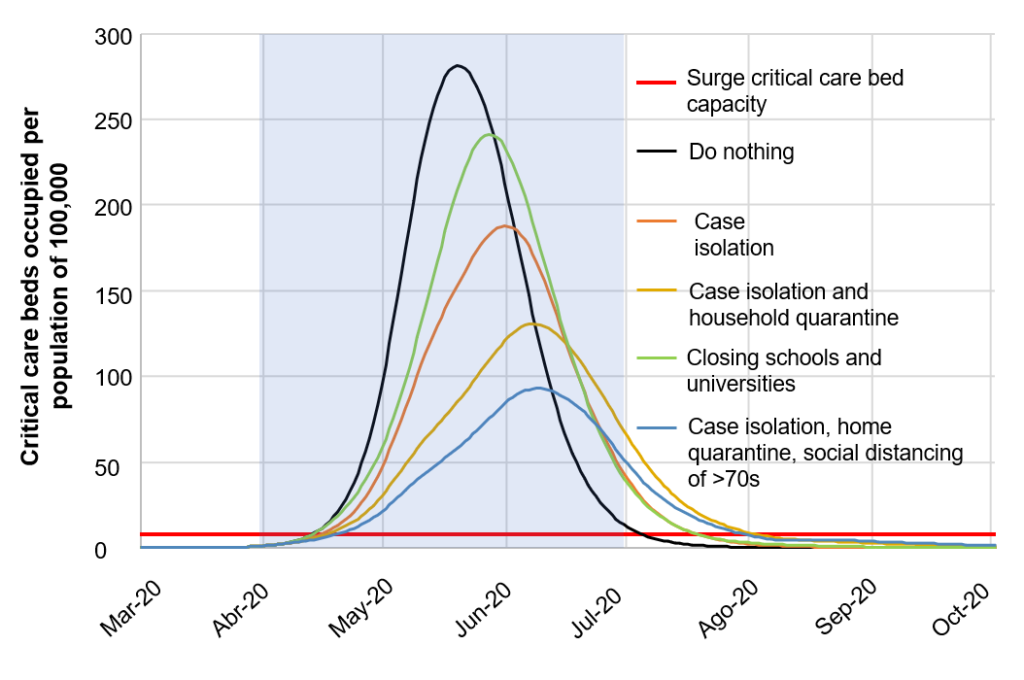

Mitigation Policies vs. Suppression Policies

In addition to evaluating these policies individually, the article evaluates combinations of policies, grouped in two categories: mitigation policies and suppression policies. While mitigation policies seek to “flatten the curve,” they are completely insufficient—even in the case of the most ambitious combinations, which includes three months of isolating symptomatic cases, voluntary quarantine of family members, and social distancing of those over the age of 70 for four months. In this case, the number of deaths in the United Kingdom drops by 50% (which is still completely unacceptable) and the peak demand for critical care beds declines by 67%. Even so, available capacity is exceeded by a factor of more than 10.

Figure 2: Mitigation Measures

Source: Ferguson et al. (2020).

Suppression is much more effective, but there is a catch: Once the policy ends, there could be a spike that is just as serious as in the unmitigated case. Essentially, the measures would only be buying some time. Why is this? It has to do with insufficient herd immunity.

The Importance of Herd Immunity

Vaccination campaigns do not solely protect those receiving the vaccine. They also protect the rest of the population. By providing immunity to a portion of the population, the basic reproductive number, R0—that is, the average number of people infected by each sick person—is reduced. The more people are vaccinated, the lower the probability of infection. Thus, vaccination produces herd immunity and contributes to halting the advance of a disease.

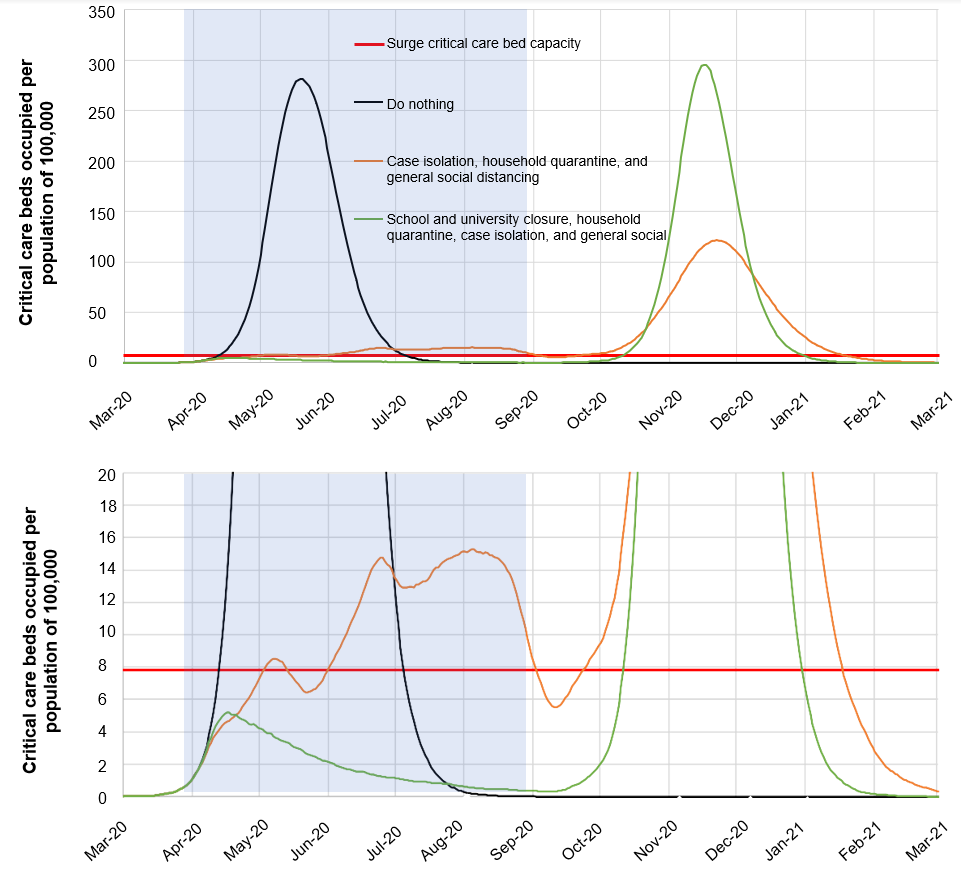

In the absence of a vaccine for COVID-19, immunity is achieved through exposure to the virus. The higher the percentage of people exposed, the greater the herd immunity and the lower the expected peak in the affected population once suppression policies end. This is shown in Figure 3, which tracks demand for critical care beds with the application of these policies over five months.

Figure 3. Suppression Measures

Source: Ferguson et al. (2020).

This graph (the lower panel is a magnification of the top panel) models the impact of two policy packages. The first includes isolation of symptomatic cases, voluntary home quarantine, and social distancing for the entire population. The second package also includes the closure of schools and universities.

As one would expect, the more aggressive package (including school and university closures) is more effective at fighting the virus. During the suppression period, the illness seems to be under control, and the number of critical care beds needed is well below the threshold. However, once this suppression period ends, there is a spike in infections that is almost identical to the unmitigated case. Of course, this approach does buy time. However, even with hospital capacity doubled, the system would still be completely overwhelmed.

With the less ambitious option, which leaves schools and universities open, the extent of suppression is lower, but so is the subsequent spike in infection. This is because, in the interim, herd immunity is strengthened. Still, this option does not prevent the collapse of the healthcare system.

Of course, one could simply extend the application period of the suppression policy. In the most aggressive case, the hope would be that the virus disappears completely, or that a vaccination or treatment emerges (clinical trials have already begun, for both vaccinations and drugs, but these are long processes). In the least aggressive case, extending the application period for the suppression policy by a few months could produce sufficient herd immunity to prevent a later spike in infections. One could even combine these policies to start with the aggressive policy combination (for example, for the first three months) and then, once demand for hospital beds is reduced, open schools and universities. This combination could give authorities more time to increase hospital capacity, possibly even making such an increase unnecessary.

Why not follow this policy? One possible reason could be behavioral fatigue. This is essentially the risk that the population loses patience, and that as the suppression policy period increases, so does noncompliance. Of course, the possibility of behavioral fatigue is a hypothesis that would have to be tested. There is a lot we still do not know about behavior in times of crisis. What we do know for sure is that the longer the suppression process extends, the greater its negative impact on the economy.

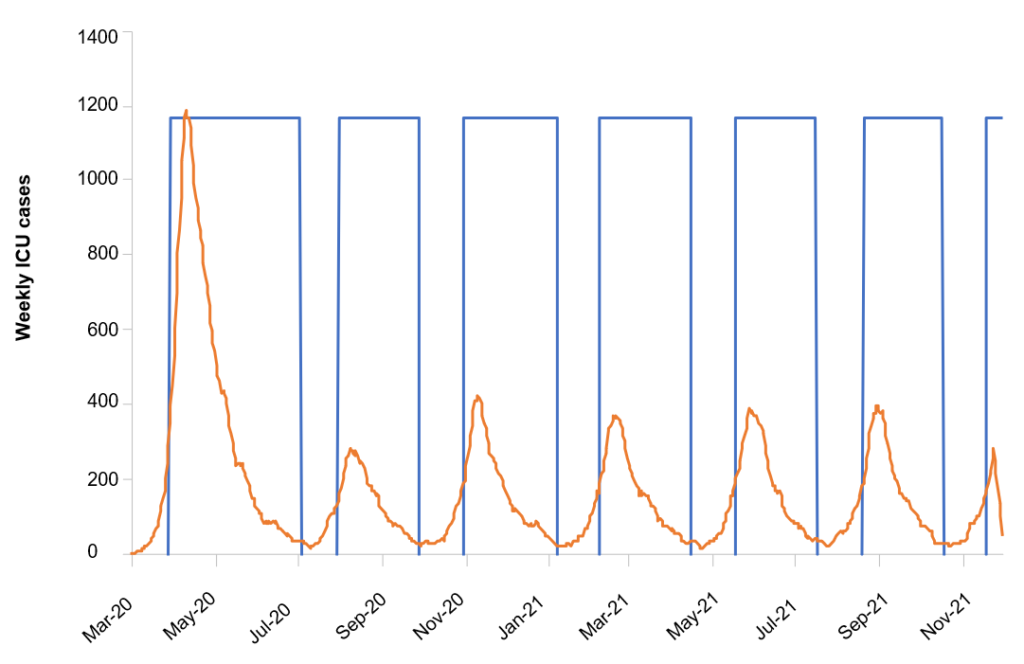

One alternative the study puts forward is that of a recurring suppression policy, in which the contents of the policy package change based on the number of new cases requiring critical care. When the number of cases crosses a certain threshold, it triggers policies that are later halted once the number of cases falls back below a lower threshold. Demand for intensive care in this case is shown in figure 4. This simulation assumes that only social distancing and school/university policies change based on these triggers, with the isolation of symptomatic cases and home quarantine remaining in place.

Figure 4. Recurring Suppression

Source: Ferguson et al. (2020)

The number of deaths in such a scenario, using triggers of 200 weekly cases and an R0 of 2.4, is 24,000 (versus 510,000 in the case of doing nothing), and peak demand for critical care is 3,400 beds (below the available number of approximately 5,000). Under this intermittent model, the suppression policy is active 74% of the time. Moreover, the number of deaths can be reduced to less than half if the threshold triggering suppression is reduced significantly.

In Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis is the worst health crisis in 100 years. Its impact in terms of loss of life is already extensive but is sure to become much worse. The good news is that, after vacillation by some countries, governments are finally taking this crisis very seriously. Still, public policy is being made in the dark, with significant uncertainty as to the behavior of the virus as well as the population, and without clear evidence on what works and what doesn’t. Also, in many cases, testing capacity is not sufficient to identify those infected, even before they show symptoms (with South Korea being an exception here).

In this context, models like the ones used by these Imperial College researchers can be very useful guides for public policy decision-making. In fact, they have already had significant influence on how the United Kingdom and the US are approaching this crisis. They can also be useful when considering approaches to fight the virus in Latin America.

Some courses of action seem clear. Capacity to test the population for infection must be increased, and by a lot. Hospital capacity also must be increased, as it was in Wuhan, China, and as New York Governor Mario Cuomo is calling for. But as this study from Imperial College demonstrates, increased hospital capacity, even when accompanied by mitigation measures, is not enough. Social distancing measures need to be implemented immediately, including not only closing schools, but closing bars, restaurants, and sporting events. There will be time later to think about re-opening them, avoiding new peaks. The time to act is now.

Leave a Reply