On March 10, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus global health crisis a pandemic. In using this term, it sought to send a message to the countries responding slowly to a disruptive health crisis with an uncertain outlook and consequences that were difficult to anticipate. Although in Latin America and the Caribbean the first cases of Covid-19 were reported in February—in Brazil and Mexico—it wasn’t until after the WHO’s declaration that the countries of the region began to implement measures requiring total or partial social distancing, which in many cases became lockdowns (quarantine).

Social isolation and confinement measures have economic, physical, and social impacts that expose the structural weaknesses of the countries of the region and threaten to undermine citizen well-being, especially of the most vulnerable populations. At the same time, what is known about the virus, the availability and trustworthiness of serological testing, and a multitude of other factors make decision-making difficult.

Thus, the question of how to emerge from these restrictions is being studied by universities, international organizations, think tanks, and governments. Here are a number of proposals they have come up with.

What Do the Proposals and Practices of Developed Countries Have in Common?

The proposals generally establish different phases in the process of loosening restrictions, from movement without needing any type of permission and opening some businesses to restarting public events and international travel.

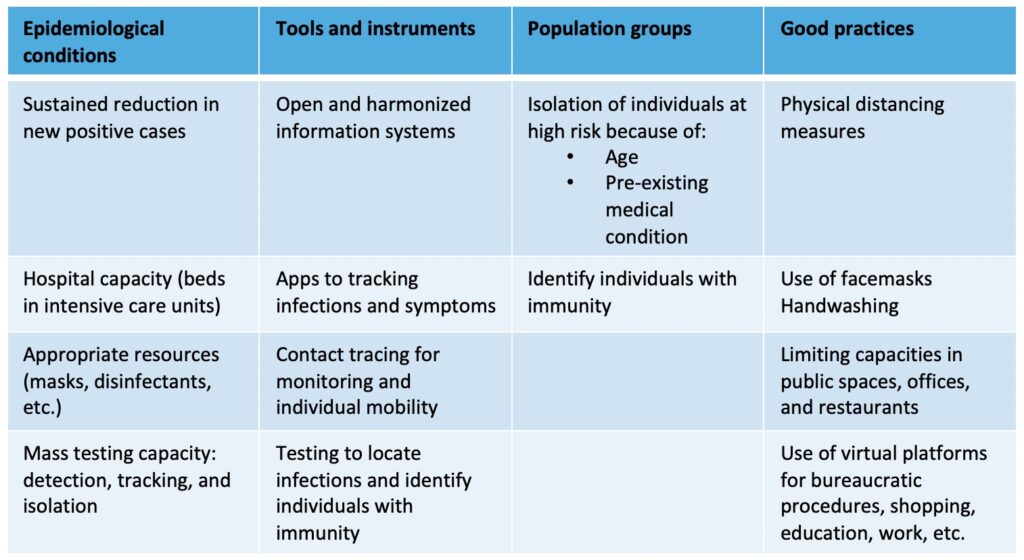

To move from one phase to the next, the proposals suggest a series of epidemiological and public health conditions in order to evaluate whether the measures have been effective or not. On one hand, the number of positive Covid-19 cases must be in steady decline for a specific amount of time (which may vary between countries). On the other hand, the hospital system must have the necessary capacity to handle all infected patients who are in serious condition. There are different criteria for measuring hospital capacity.

Governments need a series of tools to evaluate these two dimensions. They need harmonized and updated information on infection rates, broken down as much as possible by geographic area and population group. They also need digital tools to track infected individuals and identify their network of contacts. And it is crucial to have enough tests for people who are infected or have been exposed to infected individuals.

For a targeted lifting of restrictions, governments should also take into account that some groups are more vulnerable than others based on their age or possible pre-existing conditions. Additionally, infection rates could be higher or lower in different regions, making it crucial to involve local governments.

Lastly, there is consensus on the need to promote good health and safety practices to mitigate everywhere the risk of infection. Physical distancing is key, especially in enclosed spaces. Also important is the use of masks, washing or disinfecting hands, and minimizing contact with surfaces and objects.

Lastly, all services or interactions that can be carried out remotely must be offered on virtual platforms so they can continue functioning: telecare, telework, remote learning, telemedicine, bureaucratic procedures, shopping, bills, etc.

Areas without Explicit Criteria or Consensus

Despite the many points of agreement between the different proposals for gradually emerging from lockdown, there are areas where the political, cultural, social, and institutional norms of each country make decision-making difficult and where there is less consensus on practical and functional criteria for establishing them.

For example, the proposals analyzed are quite vague with regard to which population groups must remain in confinement for a longer period of time.

- Although most proposals assume there are groups that should remain in isolation for longer due to their increased risk of death in case of contracting the virus, none of them set a minimum age at which older adults should remain in confinement. They also fail to detail the pre-existing medical conditions that should cause a person to remain in isolation.

- Another thing to take into account is that by loosening restrictions in certain areas of the country but not others, in practice, internal borders are created that can be difficult to control and to justify constitutionally.

- Also, the Covid-19 immunity certificates or passports mentioned in some proposals are plagued with medical, ethical, and practical problems that make their implementation difficult. For example, it is still unclear if people who become infected with Covid-19 and recover acquire long-term immunity. Additionally, issuing certificates could incentivize certain individuals to seek to contract the illness just to get one, or lead to legal battles over discrimination.

- For multigenerational homes or homes with high risk individuals to maintain strict measures of isolation, or for homes that are overcrowded to be released from confinement first, would require very detailed information on each home. Such information is rarely available to the authorities who dictate and oversee such measures.

The option of returning to work on certain assigned days and schedules is also plagued with practical limitations, as a coordinating entity is required to prevent multiple companies and sectors from using similar schedules and causing crowding in public spaces.

- Another question with little consensus is which sectors to reopen first. Some proposals would prioritize sectors with a greater relative contribution to local or national GDP. Others suggest prioritizing labor-intensive sectors to boost job recovery, or sectors with a lower risk of the spread of infection because they are highly automated or can operate virtually.

In practice, many of the decisions on reopening made so far have not necessarily been based on objective criteria but are rather a reaction to the influence of business and labor groups and based on unwritten cultural and social preferences.

Fewer Transition Protocols in Latin America and the Caribbean

- As we have seen, most proposals on emerging from isolation use strictly technical criteria and considerations but are vague on gray areas where there is less consensus and where social, cultural, and political preferences tend to be very influential. In Latin America and the Caribbean, there is less of an emphasis on proposals for transition or gradual emergence from lockdown—both from government officials and researchers—that would help guide the countries of the region’s next steps. However, the gradual plans that do exist (in countries like Argentina, Barbados, and Costa Rica) are in line with the good practices and proposals reviewed herein.

- For more on the strategic considerations that should be taken into account by countries when deciding how to emerge from confinement and recommence economic activities, download our publication.

Leave a Reply