Despite tremendous strides towards economic stabilization, fiscal responsibility, and debt reduction, financial sector development, access, and inclusion in Jamaica lag behind many of its peers. Recent improvements in institutional capacity, policy discipline, and structural factors suggest that there is considerable scope to accelerate financial sector development and to broaden access and inclusion. A recent IDB publication entitled: “Jamaica: Financial Development, Access & Inclusion—Constraints and Options” (Nov. 2018) reviews related issues, highlights key country-specific challenges, and discusses areas for reform.

In this first of two blog posts, we review the history of financial development in Jamaica—particularly credit markets—, and how policies and economic performance have held the country back. In Part II of this series of posts, we will turn our focus to the related issues of financial access and inclusion, including country-specific barriers, as well as potential reforms to help improve related outcomes.

Listen also to this related discussion between IDB Lead Economist Henry Mooney and Golda Lee Bruce as part of a new feature from IDB’s Caribbean Country Department: Improving Caribbean Lives podcasts for in-depth discussions of emerging Caribbean development ideas and trends.

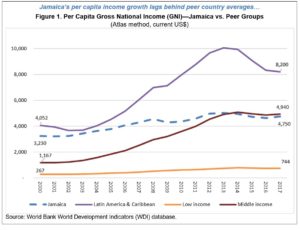

Jamaica—history of slow income growth and development. Jamaica is a small, open, middle-income economy, characterized by modest growth rates and high debt levels. Jamaica’s history of development is plagued by slow growth, crises, and only modest progress toward poverty reduction and development. Per capita income levels have increased by about 86% (nominal) from 2000-2017—from a gross national income (GNI) per capita of US$3,230 to about US$4,750 (Figure 1). However, over the same period, average per capita income grew by nearly 450% for the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region as a whole—from US$1,167 to US$4,940—, and by about 180% and 156% for middle- and low-income countries, respectively.

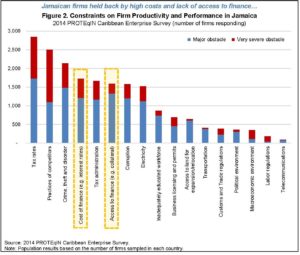

Costs and access to finance are a key impediment to productivity and growth. Jamaican firms responding to the 2014 PROTEqIN Caribbean enterprise survey[3] ranked access to finance and the costs of finance as among the most significant constraints that they face regarding firm-level productivity and performance (Figure 2). Other constraints identified include tax rates and administration, competitor business practices, crime and disorder, electricity, and corruption.

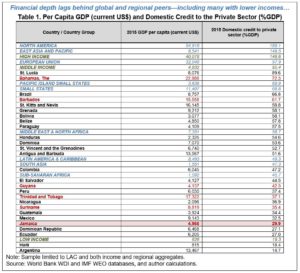

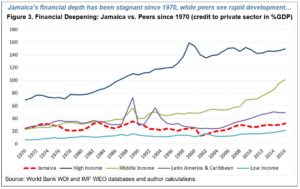

Jamaica’s financial sector is shallow relative to other countries. Jamaica’s ratio of domestic private credit[4] to GDP of 30% in 2015[5] (estimated at 32 in 2016)—a common indicator of financial sector depth[6]—was well below the average for: middle-income countries[7] (94%), all LAC countries (49%), and a number of comparable countries across the world (see Figure 3). The private credit market was also shallower than the average for Sub-Saharan African countries (46%)—a region where successful policy efforts and progress toward increasing financial access have been observed in recent years. Within the LAC region, Jamaica ranked near the bottom for financial depth in 2015, behind only the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Haiti, and Argentina (Table 1).

Financial deepening in Jamaica has been stalled for nearly five decades, while regional and income peers have seen rapid accelerations. Financial deepening in Jamaica has been largely stalled since 1970, in part owing to policy inconsistency driving poor performance, external shocks, and financial crises. Private credit-to-GDP ratios have accelerated by an average of only 0.25 percent of GDP per year between 1970 and 2016 (see Figure 3). In comparison, the average for other middle-income countries (in the aggregate) has increased from the same level in 1970 (about 22 percentage points of GDP) by a factor of four through 2015, reaching 95 percent of GDP in 2015.

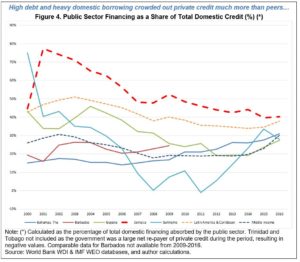

Financial underdevelopment stems in part from fiscal and policy indiscipline. High debt levels and substantial government borrowing constrained private credit and financial development. This forced the government to rely heavily on domestic markets—particularly the banking system—to meet funding needs (Figure 4). This crowded out private financing, as banks and other lenders allocated most of their lending capacity to the government rather than businesses and individuals. Of the Caribbean countries assessed, Jamaica displayed the highest average share of domestic financing to the public sector from 2000 to 2016 (53 percent). This was also much higher than the average for other countries in the LAC region (41 percent), and middle-income economies (23 percent). From 2001 to 2006, government crowding out reached as high as 77 percent, and averaged over 70 percent between 2001 and 2005. Put another way, there have been periods during which as little as one-fifth of domestic credit capacity has been available to the private sector for borrowing and investment.

Policy failures also disincentivized investment. Policy indiscipline also resulted in high inflation, currency depreciation, and interest rate volatility, distorting incentives to save, consume, and invest. The long history of fiscal indiscipline has driven losses for investors in real terms. This contributed to high and volatile rates of inflation as well as high domestic interest rates. For example, inflation (as measured by the change in the annual average consumer price index) averaged over 16 percent per year from 1990 to 2016, with a standard deviation of 16 percent, and a single year peak of nearly 80 percent in 1992. This drove large positive inflation differentials with key trade partner currencies such as the US dollar, contributing to depreciation pressures. In this context, the Jamaican dollar depreciated by an average of 14 percent per year against the US dollar from 1990 to 2016, and by as much as 90 percent in a single year. Taken together, these factors have created considerable uncertainty in terms of investment, and distorted incentives to save in domestic currency and regarding consumption, leading to considerable dollarization of deposits and assets. In this context, more than 45 percent of deposits were denominated in US dollars in 2016, making Jamaica’s level of deposit dollarization among the highest in the region.

Part II: “Why is financial inclusion so important, and what related challenges and opportunities does Jamaica face?” Our next blog post will assess other factors beyond financial sector depth and development, and will focus on country-specific challenges facing the small and medium-sized enterprises and individuals in accessing credit and financial services in Jamaica. The country’s first financial inclusion strategy is also reviewed, as well as potential options for improving conditions for firms as well as the under- and un-banked.

[1] Financial services can include any form of transaction, payment, savings, credit, and insurance.

[2] See the following for additional information: http://www.uncdf.org/financial-inclusion-and-the-sdgs

[3] PROTEqIN is a Caribbean enterprise and indicator survey, first undertaken as part of the World Bank’s 2010 Latin American and Caribbean Enterprise Surveys (LACES). It was last updated in 2014. The methodology was designed to attain two key objectives: 1) benchmarking economies’ business and investment climates across the world; and 2) assessing effects of conditions and changes in business environment constraints on firm-level productivity and performance. The sample size for Jamaica included 242 firms for which data was collected. The project was sponsored by Compete Caribbean, which is funded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and the Government of Canada.

[4] Private credit includes funds provided to the private sector by financial corporations—e.g., loans, purchases of non-equity securities, trade credit, and other accounts receivable establishing a claim.

[5] At the time of publication, 2015 was the latest data point available for Jamaica included in a comparable cross-country dataset—from the World bank data portal, based on IMF International Financial Statistics and data files, and World Bank and OECD GDP estimates. Data published by the IMF in April of 2018 listed credit to the private sector at about 29% of GDP at end-March 2018.

[6] See IMF, “Financial Sector Assessment—A Handbook”, for a discussion of related measures.

[7] Income groups are defined as per the World Bank’s definition, with middle-income countries defined as those with a 2015 GNI per capita between $1,026 and $12,475, and low-income countries as those with a GNI per capita below $1,026 in the same year.

To listen more of our podcasts in the Improving Lives in the Caribbean series, click here.

Leave a Reply