Here is a new feature from the IDB’s Caribbean Country Department: Improving Caribbean Lives podcasts for in-depth discussions of emerging Caribbean development ideas and trends. Listen to the series included in some of our blogs and also available on SoundCloud.

A recent Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) publication entitled: “Jamaica: Financial Development, Access & Inclusion—Constraints and Options” (Nov. 2018) undertakes an in depth assessment of the linked issues of financial development, access, and inclusion for Jamaica, with a view to identifying common and country-specific barriers to progress, as well as potential areas for reform. Using the analytical methodology developed for Jamaica, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) economists from across the Caribbean region—including Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago—undertook preliminary assessments of related issues for their respective countries, as outlined in: “Financial Depth, Access, and Inclusion in the Caribbean” (March 2019).

As an accompaniment to these publications, IDB Lead Economist Henry Mooney recorded a series of podcasts defining financial depth and inclusion, highlighting their importance for economic development, and discussing findings from the above-mentioned paper on Jamaica. Related concepts are also discussed below.

What do we mean by financial development and inclusion? Financial depth and development, access, and inclusion are distinct but related concepts, particularly for developing countries.

- Financial depth generally refers to the degree to which financial markets—particularly credit markets—are sufficient to meet the needs of domestic agents, including the public and private sectors.

- The concept of financial development extends beyond the sufficiency of markets to include a broader set of financial instruments and services, including securitized assets (e.g., debt and equity), synthetic instruments (e.g., futures, forwards, options, etc.), and other financial services (e.g., pensions, insurance, etc.).

- Financial access focuses on the degree to which actors are able to make use of financial products and services, regardless of the degree to which the market is developed—for example, where public entities have ready access to financial products and services, while private agents have difficulty doing so.

- Financial inclusion focuses on the ability of vulnerable and marginalized groups within a country (e.g., small and micro enterprises, those in the informal sector, poor and/or rural communities, minorities, etc.) to participate in the financial system or to make use of related services such as deposit accounts, borrowing, insurance, pensions, etc.

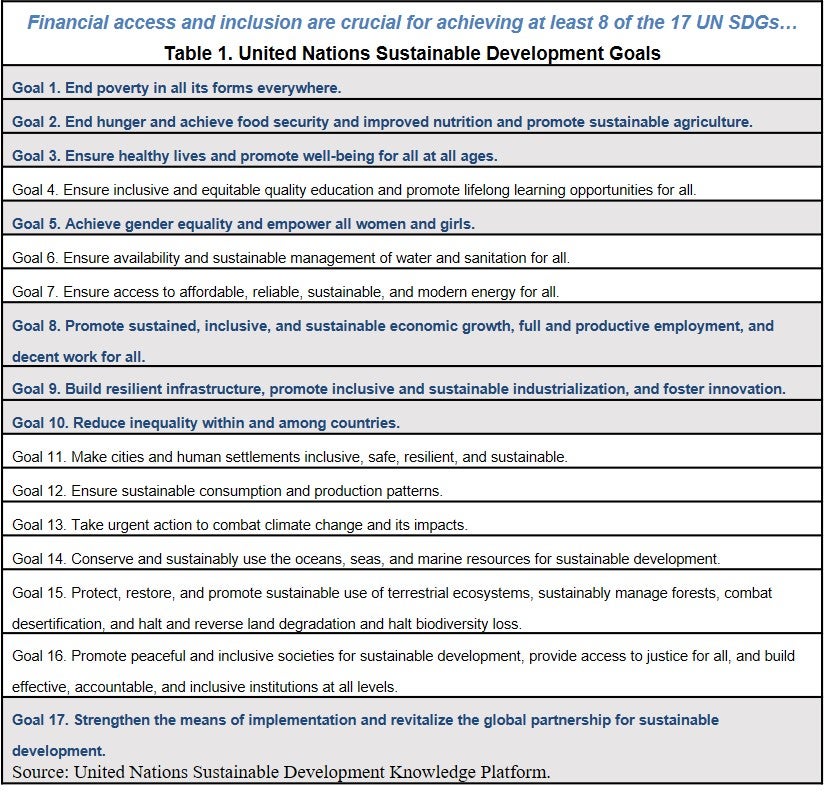

Link to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Financial access and inclusion are considered to be among the most important building blocks for achieving the 2030 SDGs, and related issues are featured as targets in at least 8 of the 17 goals (highlighted in blue in Table 1).

Costs and Access to Finance: A Crucial Challenge for Caribbean Countries. The cost of finance and access to finance are key impediments to firm productivity and performance in the Caribbean. For example, Caribbean firms responding to the 2014 PROTEqIN[1] Caribbean Enterprise Survey ranked the costs of finance and access to finance as among the most significant constraints that they face to improving firm-level productivity and performance (Figure 1). Other significant constraints commonly identified included tax rates and administration, competitor business practices, crime and disorder, electricity, and corruption. In this context, addressing obstacles to financial development, access, and inclusion in the region must be considered a key component of effective country development strategies.

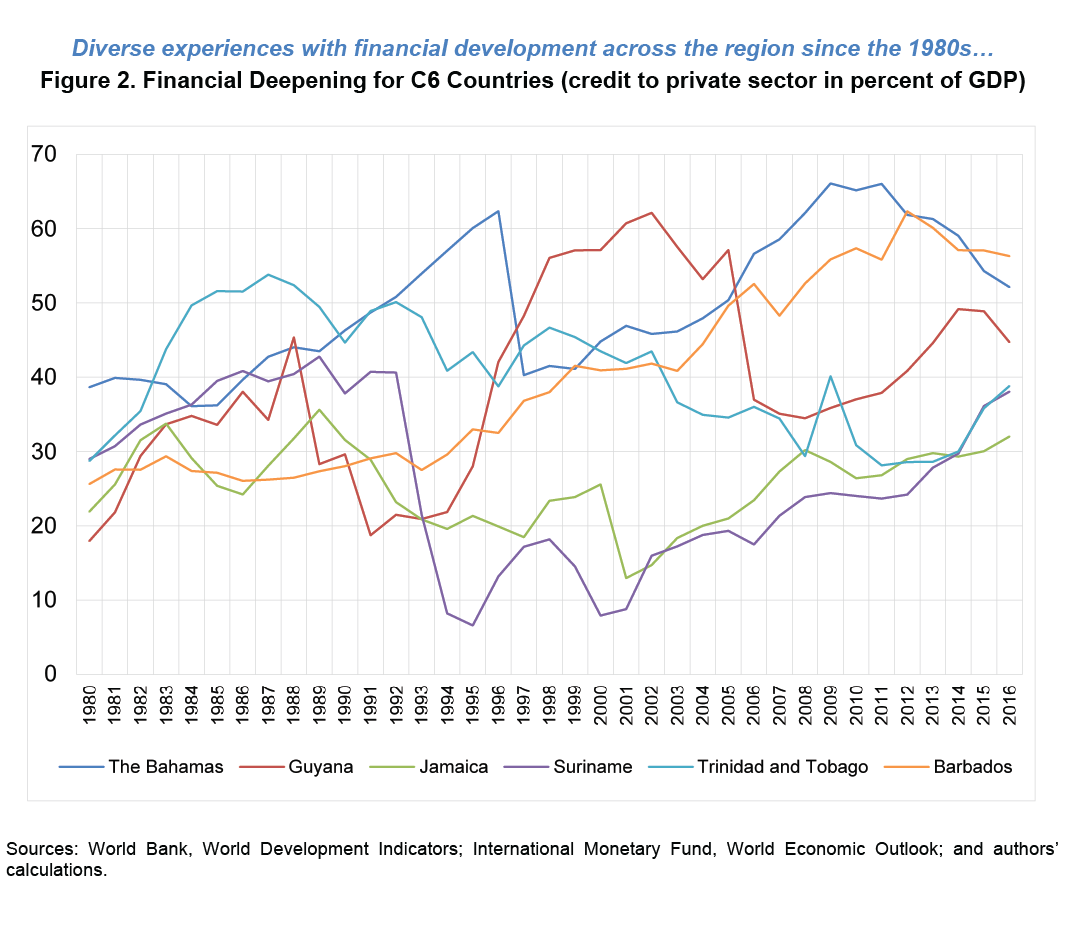

Financial Development across the Region—Broad Range of Outcomes. Caribbean countries are diverse in terms of their economic structure, geographic and demographic characteristics, income levels, and other socio-economic features. Not surprisingly, this is also true in terms of countries’ levels of financial depth and development. For example, the ratio of domestic private credit to GDP [2] in 2015 [3]—a common indicator of financial sector depth—ranged from 62 percent for Barbados, to as low as 30 percent for Jamaica. In comparison, the average was 147 percent for all high-income countries, 94 percent for middle-income countries, 19 percent for low-income countries [4], 189 percent for North American countries, 98 percent for European Union members, and 49 percent for Latin American and Caribbean countries as a whole (Table 2).

Diverse experience since the 1980s. For some Caribbean countries, financial deepening has accelerated since the 1990s, while others have remained stagnant. Countries such as Barbados and The Bahamas have seen their financial sectors deepen appreciably since the 1980s, in line with the implementation of policies aimed at expanding the sector, including for offshore clients. Other countries like Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, and Suriname have seen market depth oscillate considerably. In this context, financial deepening has been largely stalled since 1970 for both Jamaica and Suriname, in part owing to policy inconsistency driving poor performance, external shocks, and financial crises (Figure 2). Policies, shocks, or other factors? Policies and shocks have influenced financial development across countries, but other geographic, structural, and socio-economic factors have also presented hurdles to access. High debt levels and substantial government borrowing constrained private credit and financial development in a number of countries. This forced some governments to rely heavily on domestic markets—particularly the banking system—to meet funding needs, which crowded out private financing. Policy failures and inconsistencies have also led to high and volatile inflation, as well as large swings in ether the nominal or real exchange rates for many countries over time, with implications for savings and investment behaviour. Similarly, Caribbean countries tend to be small, open economies, suffering from both climatic and economic vulnerabilities to external shocks, which have also influenced the development of financial sectors. But other factors common to many countries throughout the world have also affected these outcomes, including policies and regulatory issues, as well as socio-economic characteristics.

Policies, shocks, or other factors? Policies and shocks have influenced financial development across countries, but other geographic, structural, and socio-economic factors have also presented hurdles to access. High debt levels and substantial government borrowing constrained private credit and financial development in a number of countries. This forced some governments to rely heavily on domestic markets—particularly the banking system—to meet funding needs, which crowded out private financing. Policy failures and inconsistencies have also led to high and volatile inflation, as well as large swings in ether the nominal or real exchange rates for many countries over time, with implications for savings and investment behaviour. Similarly, Caribbean countries tend to be small, open economies, suffering from both climatic and economic vulnerabilities to external shocks, which have also influenced the development of financial sectors. But other factors common to many countries throughout the world have also affected these outcomes, including policies and regulatory issues, as well as socio-economic characteristics.

Common and Country-Specific Impediments to Broader Inclusion. Financial access and inclusion outcomes are closely and inextricably linked to financial development and depth. Shallow and underdeveloped sectors are rarely able to serve the needs of marginal and vulnerable communities. But other factors beyond financial depth and development also affect the ability of poorer people, rural communities, small and micro enterprises, or other marginalized and challenged groups to take full advantage of banking and finance. While impediments to financial access and inclusion can vary considerably across countries, and range from policy and regulatory hurdles to geographic and cultural factors, many have emerged as common challenges.

Cross-country evidence. For example, the World Bank’s “Global Financial Development Report 2014: Financial Inclusion” provided an extensive analysis of financial development, access, and inclusion issues. This analysis identified seven major reasons why people from both developed and developing countries do not own or use formal bank accounts, based on a cross-country survey of 70,000 unbanked individuals across regions. As shown in Figure 3, the survey found that a lack of financial resources (number 1), high costs of opening and maintaining accounts (number 3), lack of accessibility of financial service providers (number 4), and a lack of required documentation (number 5) were among the most common reasons for remaining outside of the formal financial system. Many of the impediments to financial inclusion identified from this cross-country survey are relevant to Caribbean countries.

Country focused diagnostics. For an in-depth discussion and assessment of related issues for Jamaica, see: “Jamaica: Financial Development, Access & Inclusion—Constraints and Options” (Nov. 2018). For a preliminary analysis of outcomes and challenges related to financial development and inclusion for other countries in the Caribbean region—including Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago—see: “Financial Depth, Access, and Inclusion in the Caribbean” (March 2019).

[1] Productivity, Technology, and Innovation in the Caribbean (PROTEqIN) is an enterprise and indicator survey first undertaken as part of the World Bank’s 2010 Latin American and Caribbean Enterprise Surveys (LACES). It was last updated in 2014. The project was sponsored by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), and the Government of Canada.

[2] Includes funds provided to the private sector by financial corporations (e.g., loans, non-equity securities, trade credit, etc.)

[3] At the time of this publication, 2015 was the latest data point available for a comparable cross-country dataset. The data are from the World Bank’s data portal, based on the IMF’s International Financial Statistics and data files and on GDP estimates by the World Bank.

[4] Income groups are defined per the World Bank’s definition, with middle-income countries defined as those with a 2015 GNI per capita between US$1,026 and US$12,475, and low-income countries as those with a GNI per capita below US$1,026 in the same year.

You can listen more podcasts from our Improving Lives in the Caribbean series here.

Leave a Reply