After two tumultuous years, 2023 remains characterized by headwinds facing countries across the world. Our previous publications have highlighted the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 shock to economies across the Caribbean region, particularly given its extreme dependence on external demand for resources, tourism, and finance. Just as the pandemic’s effects began to dissipate in 2021, a new series of shocks emerged to test Caribbean economies’ fragile recoveries and resilience in 2022, linked in large part to residual impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on supply chains and demand conditions, rising inflation and tightening financial conditions, as well as new global shocks — particularly driven by the conflict in Ukraine.

The latest edition of the IDB’s Caribbean Economics Quarterly (December 2022) points to increasing risks driven by these external headwinds, against the backdrop of weaker fiscal and financial conditions of countries still recovering from the pandemic. These constraints point to the need for targeted and efficient policy responses, focused primarily on the most vulnerable and deployed in ways that provide the highest dividends. These and related issues are discussed in our publication, as well as country specific sections providing greater detail on policies and emerging risks.

Rising commodity prices have affected the terms of trade…

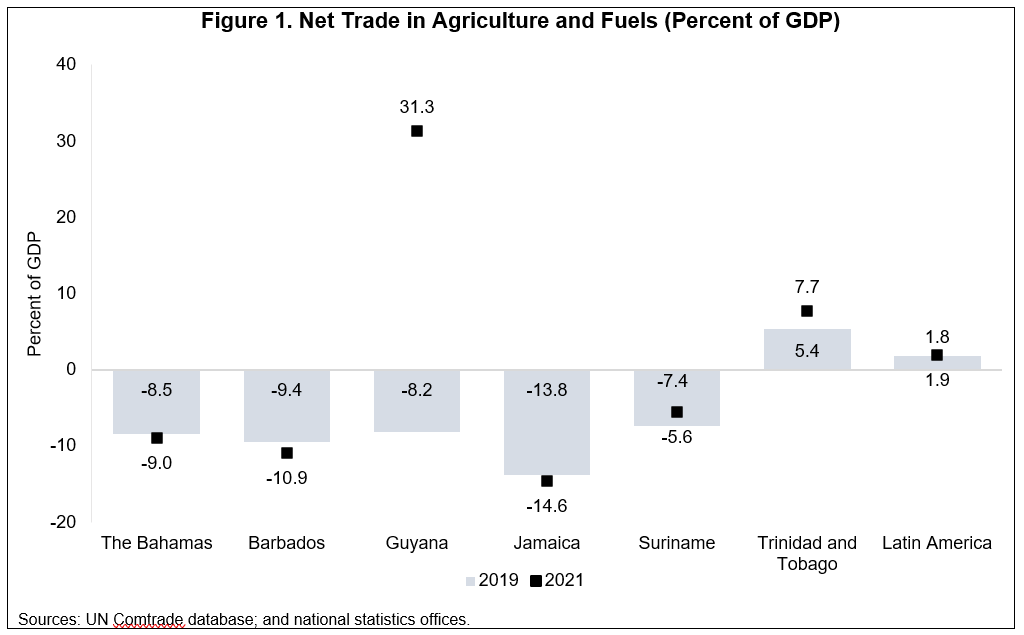

Rising hydrocarbon prices have had an obvious positive effect for net exporters, and the inverse for net importers. The case is similar for net exporters and importers of agricultural commodities. One simple way to measure the potential impact is to look at the net trade value of these commodities as a share of GDP. For net importers (The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, and Jamaica), net imports of hydrocarbon and agricultural commodities ranged from about 5% to 15% of GDP in 2021 (see Figure 1). This implies that substantial price increases of those products can have a significant impact on the trade balance and real incomes.

Food and fuel price shocks

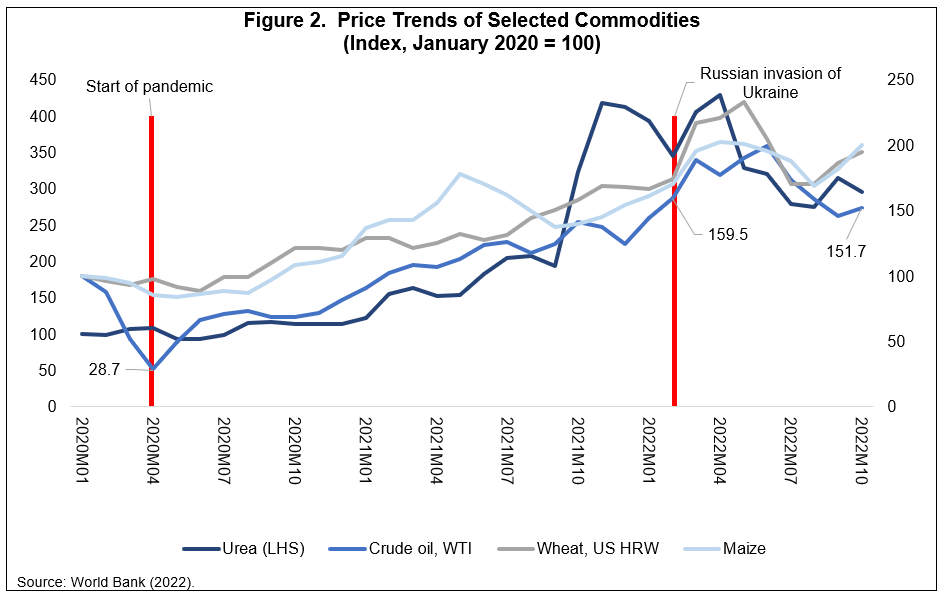

Since January 2020, the global prices for wheat, urea, crude oil and maize have risen by 51%, 95%, 100% and 195%, respectively (see Figure 2). Initially, the pandemic resulted in supply chain bottlenecks, which persist to some degree today. However, the onset of the conflict in Ukraine in late February 2022 sent further shockwaves through global commodity markets—particularly for wheat, urea (a component of many fertilizers), crude oil and maize. Russia is a major producer of all four commodities, while Ukraine is a major producer of maize and wheat and, thus, the conflict has further restricted the supply of these key commodities. Although since the summer, the affected commodity markets have cooled, prices are still expected to be elevated compared to their pre-pandemic norm. There are still risks that could throttle this recovery, including unexpected weather developments, and the discontinuation of recently resumed Ukrainian grain shipments. The gradual reopening of China’s economy since December 2022 could further increase global demand for commodities, and thus place upward pressure on prices. Furthermore, pegged foreign currency rates have shielded several Caribbean economies from inflation passthrough resulting from currency depreciation, but foreign reserves will face increasing pressure as foreign interest rates progressively rise.

Rising inflation being imported from commodity price inflation…

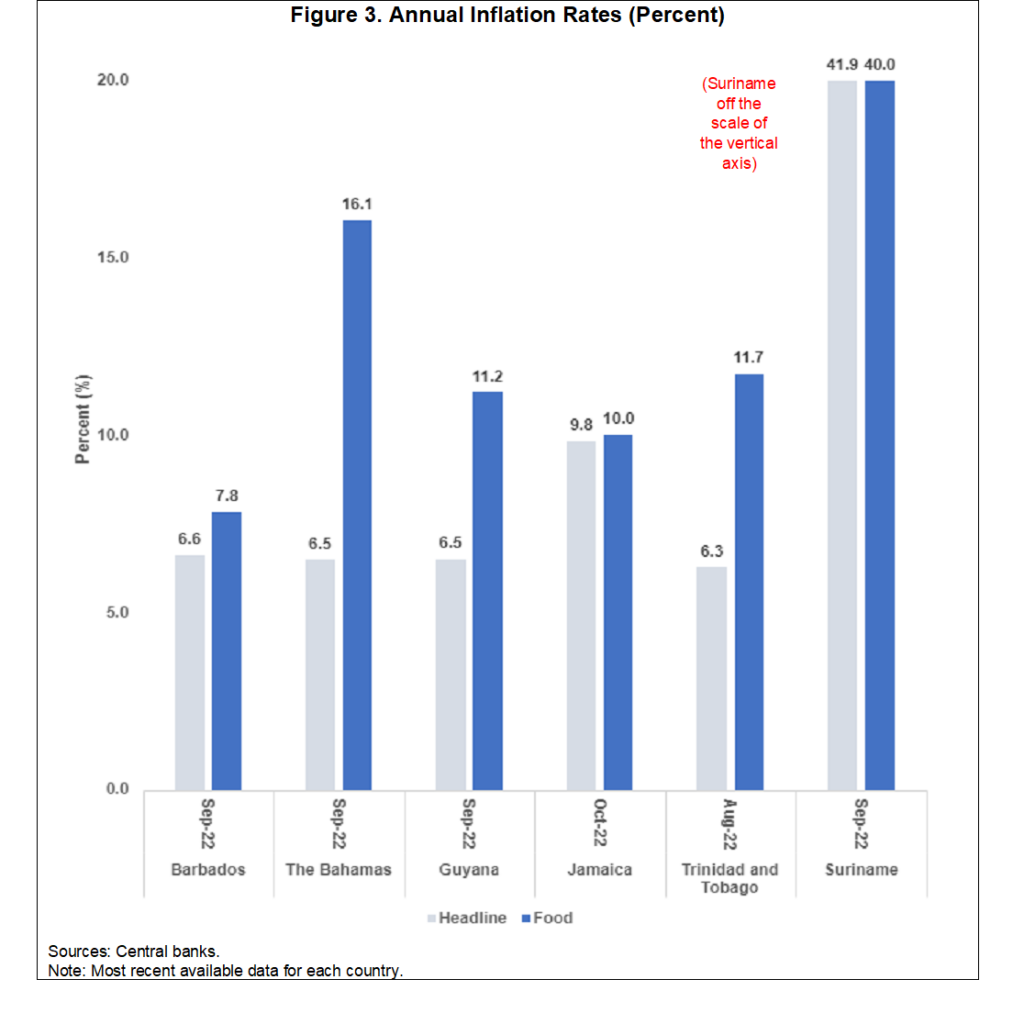

The annual inflation rate climbed to an average of 8% by mid-summer in the Caribbean countries covered in our report, excluding Suriname, which has been coping from high inflation since the fall of 2020 (see Figure 3). This average inflation rate is lower than that being experienced by many other countries elsewhere but is still very high compared to the pre-crisis period and historical standards. Against this backdrop, some Caribbean countries have undertaken active economic and monetary policies aimed at curbing price increases, but this has come at the cost of tightening financial conditions, with implications for the nascent recovery.

Tightening global financial conditions complicating recovery…

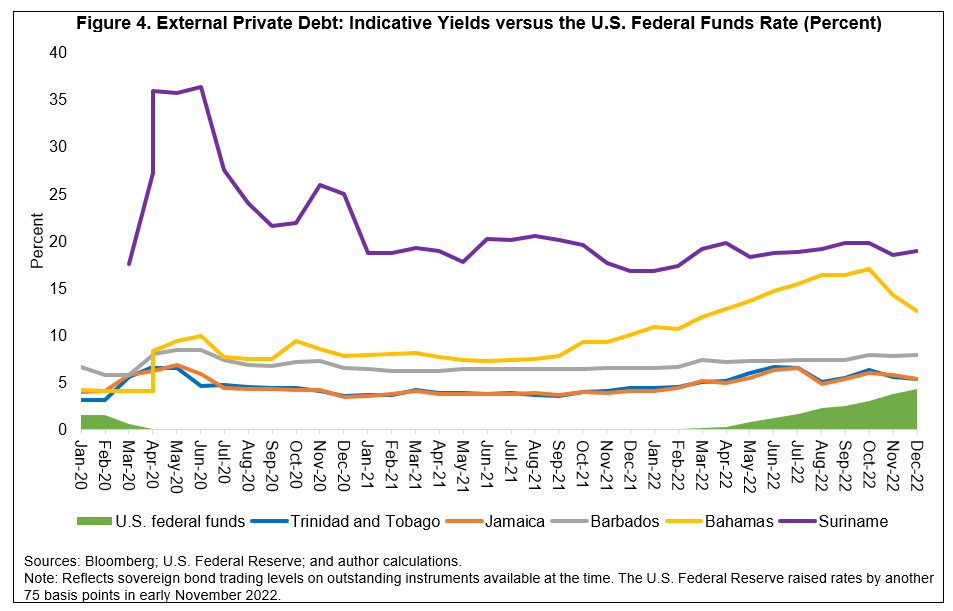

Of the converging headwinds affecting developing and emerging market economies, higher financing costs are among the most consequential. Figure 4 highlights the evolution of indicative external private sovereign funding costs for five of the six Caribbean economies between January 2020 and December 2022, set against the U.S. federal funds rate. Note that for all five economies for which data were available (excluding Guyana), the onset of the crisis in early 2020 caused indicative sovereign bond yields to increase. In some cases, this has been driven largely by higher advanced economy interest rates and related increased yields on less risky sovereign debt instruments. In other cases, these higher borrowing costs have also been driven by uncertainty and generalized market risk aversion. By December 2022, yields on outstanding private debt were higher than in January 2020; in some cases, by wide margins. Of course, it is also important to note that for many small economies, secondary markets for sovereign bonds are shallow, so spreads should be interpreted with that in mind. But regardless of the magnitude of change, increasing funding costs at home and in foreign markets have been driven by foreign economic policies, generalized risk aversion, and domestic factors linked to solvency assessments. The latter depend on fiscal and debt positions as well as external balances, which are discussed at length in our report.

Measured and targeted policy responses more important than ever

The traditional response to inflation would be to raise interest rates. The actions of Jamaica’s central bank since 2021 are a good example. Some Caribbean countries have also responded by freezing the price of electricity (effectively subsidizing the cost), and of select foodstuffs at the retail level. However, directed price controls are difficult to sustain and can create distortions in consumer choices. Given the now limited fiscal and policy space in most countries, a general recommendation is to target such measures to the most vulnerable households, and to separate interventions from the price of the commodities. Targeted cash transfers or vouchers can achieve these ends, and numerous countries around the world have implemented these types of programs in response to price shocks with great success.

Developing greater resilience in future is key…

As with most crises, this one presents an opportunity for policymakers to focus both on immediate priorities, but also longer-term initiatives that can help shield economies from related shocks in future. These and related price shocks have inspired regional leaders to promote regional structural solutions to import dependence. For example, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) has announced a “25 by 2025 Initiative” to reduce food import dependence by 25% by 2025. This promising objective could be achieved through a combination of increased domestic production and enhanced regional trade. Other such measures focused on trade, regulations, and policies aimed at regional integration and economic diversification could become a lasting positive legacy of this unprecedented period of crises and uncertainty. These and related issues are discussed at length in our report.

Leave a Reply