Did you know that Latin America and the Caribbean’s export-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions grew considerably in the last 25 to 30 years? And that both the production and transportation of goods contributed to such growth?

This is what we found in the study Footprint of Export-Related GHG Emissions from Latin America and the Caribbean, an initial step in the Inter-American Development Bank’s policy research agenda on trade and climate change which aims to help policymakers make more informed decisions on how to use trade policy to address climate change without foregoing the benefits of trade and integration. The report analyses how international trade has contributed to greenhouse gas emissions by building an extensive greenhouse gas emissions database for the production (1990—2014) and international transportation of goods exports (1990—2018) for 10 sectors and 189 countries (including 33 of the region).

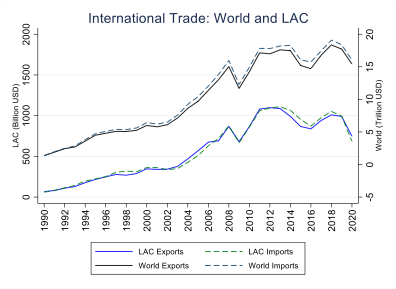

International trade has been growing globally at an unprecedented rate since the mid-twentieth century, and the region did not catch up until the liberalization in the early nineties. Since then and until the financial crisis, LAC exports jumped from US$ 67 billion to US$ 869 billion—an annualized growth rate of 15% (see Figure 1). Not only did trade flows increase considerably, but there has been a radical change in the region’s composition and direction of trade. Mining and agricultural commodities make up more than 47% of their share of sales, driven mainly by shipments to Asia whose share of LAC exports more than tripled—from 5% in 1990 to 18% in 2020.

Figure 1

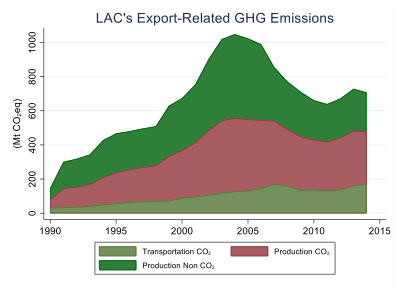

These changes in the volume, direction and composition of trade led to a significant increase in the region’s export-related greenhouse gas emissions. Between 1990 and 2004, they increased steadily from 136 to 1,049 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (Mt CO2eq) before decreasing sharply in the wake of the financial crisis. Since 2014 it has been going through an incipient recovery. (see Figure 2) These emissions can be divided into those related to production and international transportation of goods.

Figure 2

More goods, more emissions, but technology and basket became cleaner

On the production side, the distinctive feature is the region’s relatively small share of the world’s total export-related production emissions. In 2014, these emissions were 535 Mt CO2eq and accounted for only 4% of the global total. This reflects more the region’s limited share of world exports (6% in 2014, 5% in 2020) than the emission intensity of its goods. This figure for 2014 was well above that of the OECD countries and was only surpassed by developing countries in East and Southeast Asia. Among the goods exported, manufacturing accounted for most of the emissions—72% of LAC’s total—followed by mining (18%) and agriculture (10%).

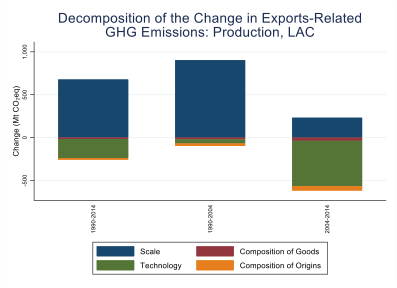

Despite its small global share, the growth of the region’s export-related production emissions has been fast, reaching 375% between 1990 and 2014. It can be broken down into four main drivers or “effects”: scale, technology, goods, and origin composition. The growth largely mirrored the significant jump in export volumes —the so-called scale effect— particularly before 2004 (see Figure 3). The other, technology and composition effects, pushed in the opposite direction. Exports became less emission-intensive (technology effect), and countries whose production (origin composition effect) and export baskets (goods compositions effect) were cleaner increased their share in the region’s exports.

Figure 3

Remoteness and heavy goods weigh heavily on emission

In a region marked by remoteness and specialization in “heavy” and bulky mineral (such as copper, iron, and petroleum) and agricultural goods (such as soybeans, maize, and sugar), transportation is bound to play an outsize role in trade flows and, accordingly, in trade-related emissions. Transporting exports to destination accounted for 24% of LAC export-related emissions in 2014, well above the world average (7%).

Its importance is also evident in absolute terms. Unlike production data, not available beyond 2014, data on transport emissions allow for a more updated picture. The data for 2018 shows that the region has one of the highest export-related transportation CO2 emissions, reaching 234 Mt or 17% of the world’s total export-related transportation CO2 emissions—well above its 6% share of world trade. Even though this share is not particularly higher than any other region, our transportation CO2 emissions per dollar worth of exports are much higher than those of the rest of the world.

In terms of modes, sea transportation is the main source of emissions. In 2018, it accounted for 53% of the total export-related transportation emissions, followed by air shipping (23%), road freight (23%), and rail (1%). From a sectoral perspective, manufacturing is the most significant driver, accounting for 55% of the overall transport emissions, and the shares for mining and agriculture are 32% and 12%, respectively.

As with production, the growth of transportation emissions can be broken down into different drivers. Here too, the scale effect was dominant, but unlike the production’s case, most of the other effects pushed in the same direction of increasing emissions. The scale effect accounted for 60% of the 188 Mt increase that occurred between 1990 and 2018, followed by partner composition (i.e., the growing share of more distant partners, such as developing Asia, which accounts for 27%), technology (12%) and goods composition (2%). The only exception was origin composition, which had a negative impact on emission growth (-1%), probably due to countries with a cleaner transport matrix gaining export share. Even though the goods composition effect does not seem important for the region as a whole, it plays a significant role in certain countries, especially Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Emissions accounting is just the first step

This rigorous accounting of export-related emissions is the first stage in IDB’s trade and climate change policy research agenda. An agenda designed to assist policymakers use trade policy to address climate change while preserving the benefits of trade and integration.

The standard approach in economics, which can be traced back to the seminal work of Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen, recommends the use of more direct tools than trade policy to address pollution externalities—say a carbon tax on fossil fuels—mainly because of the uncertainty of welfare effects and the risk of environmental concerns being captured by protectionist interests. However, political economy challenges and the systemic nature of more immediate solutions, as shown by the tribulations of the multilateral environment agreements—think, for instance, of the more recent Paris Agreement—suggest that trade policy will be called to play a role.

For instance, some of the region’s foremost trade partners are already in the process of taking unilateral trade actions. The most prominent case is the border carbon adjustment tax recently announced by the European Union, levying on imports according to their carbon content. Without good data about the carbon footprint of the region’s trade, designing optimal trade policy responses would be a guessing game.

Leave a Reply