A recent IDB report found that while trade liberalization resulted in increased firm and labor productivity in Latin America and the Caribbean over the last 30 years, boosting economic growth, it did not create as many new jobs or reduce inequality as expected.

Liberalization in the 1980s and 1990s resulted in moderate negative impacts on labor markets. For example, a 2004 study found modest declines in net employment growth in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Uruguay after each country’s period of unilateral tariff reductions.

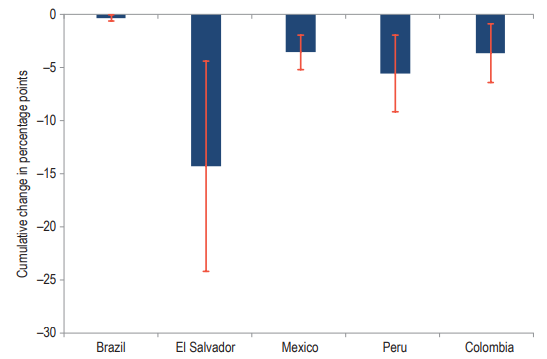

Trade-related developments abroad, such as the emergence of China as a low-cost producer of manufactured goods and global supply chain hub, also had an impact on labor markets. A series of recent IDB papers on this topic reveals that Chinese imports negatively impacted employment growth in Latin America in the 2000s. However, the impact varies by country, ranging from less than 1 percent in Brazil to 14 percent in El Salvador. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cumulative change in employment growth due to an increase in imports from China between 2000 and 2013

Source: IDB staff calculations based on firm-level estimates from Blyde and Fentanes (2019) for Mexico; Pierola, Sánchez-Navarro and Mercado (2019) for Peru; Molina (2019) for Colombia; Li and Mesquita Moreira (2019) for El Salvador; and Mesquita Moreira et al. (2019) for Brazil. Period for Peru is 2001-2013.

How can Latin America successfully lessen the negative impacts of import competition on employment? IDB research shows that the two policies below can substantially help.

-

Training accelerates transitions into new jobs

Import competition puts pressure on domestic firms to increase productivity, which often leads to lay-offs. Displaced workers may be able to transition smoothly into a new job. However, this usually does not occur smoothly for several reasons, including lack of new jobs, unfavorable macroeconomic conditions, and costs associated with switching firms, occupations or industries, such as the need for new skills.

The IDB has studied the impact of training courses offered by the National Service for Industrial Training (SENAI) in Brazil. This type of active labor training program is not directly related to trade but can still be effective in teaching new skills to workers displaced by trade.

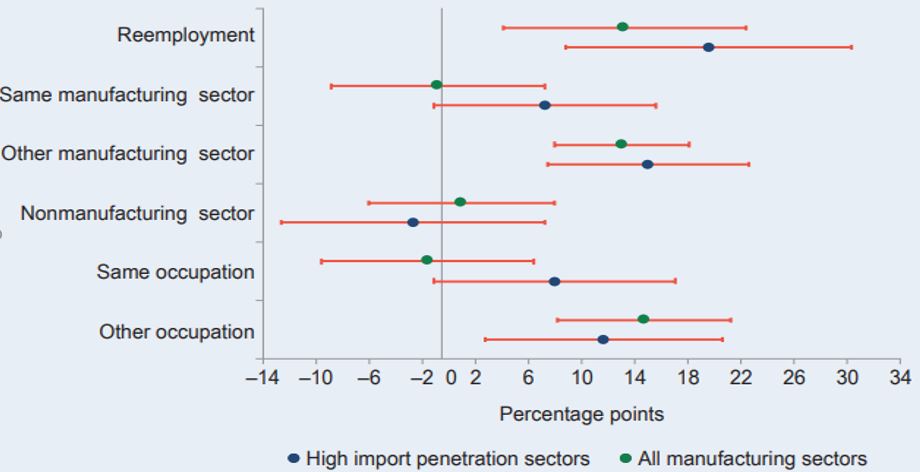

The good news, as shown in Figure 2, is that not only does training increase the probability that a displaced worker will be reemployed in a year, but that training also facilitates entry into a different manufacturing sector or occupation. The benefits of training generally are similar in magnitude for workers in all sectors and those displaced from industries with high import competition.

Figure 2. Impact of Training on the Probability of Labor Market Reentry in One Year

Source: Based on Blyde et al. (2019).

-

Preferential trade agreements boost employment

Participation in preferential trade agreements (PTAs) also can lessen the impact of import competition. While unilateral liberalization brings significant benefits, particularly if the average tariff rate in a country is high, the implementation of a PTA results in more balanced and even favorable impacts on labor markets.

A 2019 IDB study finds that while import competition from its NAFTA partners cost Mexico 450,000 jobs, expanded export opportunities generated 1.3 million new jobs, resulting in a net impact of nearly 900,000 workers, an increase of 14 percent, in the first decade of NAFTA’s existence.

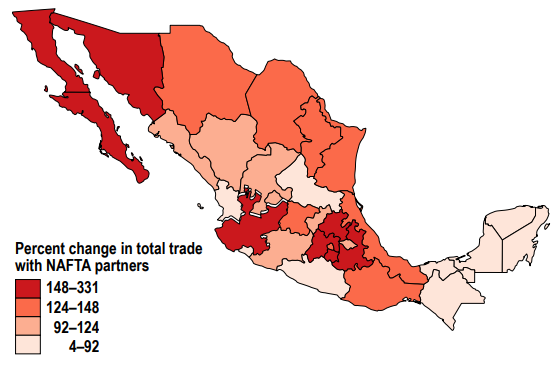

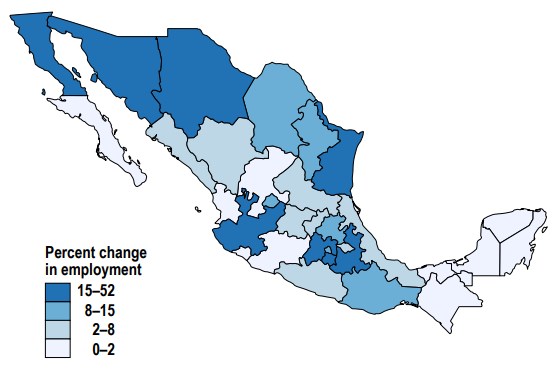

The Mexican states whose total trade with NAFTA partners grew the most also experienced the highest net increases in employment due to NAFTA, showing that more trade does not necessarily result in a net loss for workers. (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Percent change in Mexico’s Total NAFTA Trade and Trade-Related Employment by State, 1993-2003

Source: Trachtenberg (2019).

Labor and trade policies can be complementary

The evidence presented above on training programs and reciprocal liberalization reveals that labor and trade policies can create new opportunities for workers. PTAs generate new jobs in exporting industries, while training programs make it possible for displaced workers to learn the skills necessary to transition into new jobs. Both types of policies can ease the negative impacts of import competition.

For further information on how countries in the region can take advantage of these policies, download the report Trading Promises for Results: What Global Integration Can do for Latin America and the Caribbean. Chapter 4 summarizes the empirical evidence on trade and labor, including the papers behind Figures 1 and 3, while Chapter 8 focuses on labor policies and contains more details on the research in Figure 2.

Leave a Reply