In April 2010, the Eyjafjallajökull volcano erupted in Iceland, ejecting an ash cloud that shut down European airspace for days. Transatlantic air shipments of key manufacturing inputs were significantly delayed, which caused production to be put on hold in several US automobile factories. Interruptions like these incur major costs that often go far beyond the market value of the components in question and may be transmitted along the whole value chain. The Eyjafjallajökull eruption clearly demonstrates the importance of just-on-time deliveries in a world in which productive and commercial processes take place in different locations. It also highlights why punctuality is a core factor that firms need to take into account when deciding which other companies to establish trade relations with.

The time it takes for goods to travel from their point of origin to their final destination can usually be broken down into the time needed to transport the good from the factory to the port, airport or border-crossing; the time the good spends at the border; and the time it takes for it to be shipped abroad. Although a series of studies have demonstrated how domestic and international transportation times affect foreign trade, no studies to date have managed to adequately explain all the factors involved in time spent at the border and their implications. This has mainly been due to the absence of appropriate data which could be used to measure these times and assess their impact on trade.

The standard approach to measuring the total time needed to import or export goods (or to carry out some stages in these processes) has been to use survey-based country-level data from sources like the World Bank’s Doing Business report or its Logistics Performance Index. However, circumstances have changed radically with the advent of the new information systems being used by border agencies, including customs organizations and those responsible for sanitary matters, feeding, quarantining, security, and consumer protection. These systems generate real-time, high-frequency data that can be used to track all shipments through the various entry and exit procedures and to break time at the border down into the different relevant stages.

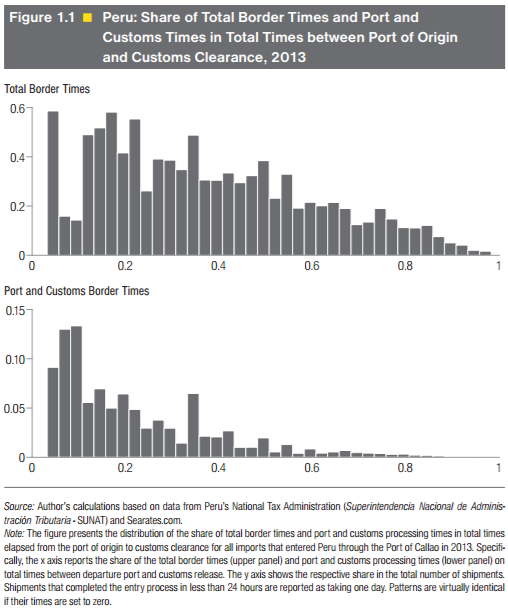

By combing through this data, we can establish whether time at the border represents a large share of the total time that it takes for a good to be shipped from its point of origin to its destination market. For example, the data on imports arriving in Peru by sea for 2013 reflect that the time that goods spent at the border represented an average 37.3% of the total time between their leaving the port in the country of origin and being released from customs. Likewise, port and customs procedures account for 21.9% of total shipping time. For 25% of shipments, total time at the border and going through port and customs procedures represented over 50% and 30% of total shipping time, respectively (figure 1.1).

This data demonstrates that, far from being linear and adimensional, borders are in fact dense spaces that are a region unto themselves. Crossing them entails a plethora of activities (such as loading and unloading, inspections, etc.) which are carried out by many different players (such as port operators and border agencies). More specifically, borders are overseen by agencies that design and apply regulations that firms must comply with and procedures that they have to implement if they want to trade internationally. The purpose of these regulations and procedures is to ensure security, safety, and legitimacy in general and compliance with fiscal rules in particular. However, the shape such institutional designs take can transform borders them into convoluted labyrinths that are time-consuming to cross.

The “thickness” of a border depends on a series of factors that include: (1) the number of government agencies involved in regulating cross-border transactions; (2) the coordination and articulation of these agencies and their regulations and procedures; (3) the design of these regulations and procedures (that is, whether they are straightforward or complex) and their specific features (for example, whether they are open 24/7 or just eight hours a day, the proportion of shipments that are subject to physical inspection, etc.); (4) the technology available for implementing the procedures in question (for example, whether customs declarations and forms are digital or paper-based) and whether there is interoperability, such that all agencies use the same forms or technology, or whether each uses its own; and (5) the existence of special regimes for firms, shipments, and trade flows, among other factors.

As a measure of border thickness, time at the border may vary for several reasons: (1) border agencies may adopt risk management systems to identify “suspect” shipments and assign them to different monitoring channels, such as document checks or physical inspections; (2) some firms are certified as reliable operators so their cargo is subject to fewer physical inspections and is dispatched more rapidly; (3) firms may be trading under standard or simplified regimes, such as exports shipped through the postal system; (4) some products require specific permits that may take longer to prepare and process, depending on whether there is a single window for foreign trade (VUCE); and (5) firms can ship goods through third-party countries via a chain of import/export procedures or under simplified, streamlined international transit regimes.

Risk management systems, authorized economic operator programs, simplified regimes for postal exports, single windows for foreign trade and regional schemes for international shipments are all trade facilitation policies that help unravel the border labyrinth and thus speed up the movement of goods across borders by streamlining administrative procedures and generally using new information technologies to implement these.

These policies, which are contemplated in the Trade Facilitation Agreement signed by the WTO Member Countries in Bali in 2013, are analyzed in detail in Out of the border labyrinth, an institutional report from the IDB’s Integration and Trade Sector. It puts forward new evidence on the impact of these policies based on transaction-level microdata that has never been used before. For the first time ever, this data allows us to observe these policies at the level at which they actually operate and analyze them using rigorous econometric methods. Future posts will discuss these policies further and examine their impacts on foreign trade in several Latin American countries.

If you would like to find out more about trade facilitation policies in Latin America and their effects on the trade performances of firms and countries, sign up for our newsletter here.

Leave a Reply