To learn more about this issue, see chapter 6 of Out Of the Border Labyrinth, a report published by the IDB’s Integration and Trade Sector, and IDB Working Paper series no. IDB-WP-704, “Transit Trade.”

International transit systems

International trade between neighboring countries is dominated by overland transportation, whereby goods are frequently shipped through intermediate countries before reaching their final destination. This is known as “international transit.” In the absence of specific schemes to facilitate such transit, goods usually have to be imported and exported at each border crossing, generating large quantities of paperwork, time-consuming administrative procedures, heavy traffic at borders, delays, all of which conspire to increase the cost of trade. In contrast, when efficient transit schemes are in place, customs clearance is postponed until goods reach their destination market, which reduces red tape at intermediate border crossings and the costs associated with this.

Some of the forebears of modern transit systems are centuries old, such as the one implemented by the duchy of Milan during the Middle Ages. More recently, in the mid-20th century, the International Road Transport (TIR) system was established in Europe. The TIR simplified border procedures and streamlined trade between countries before evolving into a common transit regime for the European Union. At present, the most advanced transit systems entail unified border control procedures, a single, standardized customs form, and online document processing. Unfortunately, most developing countries do not have transit regimes that function properly. One notable exception is Central America’s International Goods in Transit (TIM) system, which is the focus of this post.

The TIM

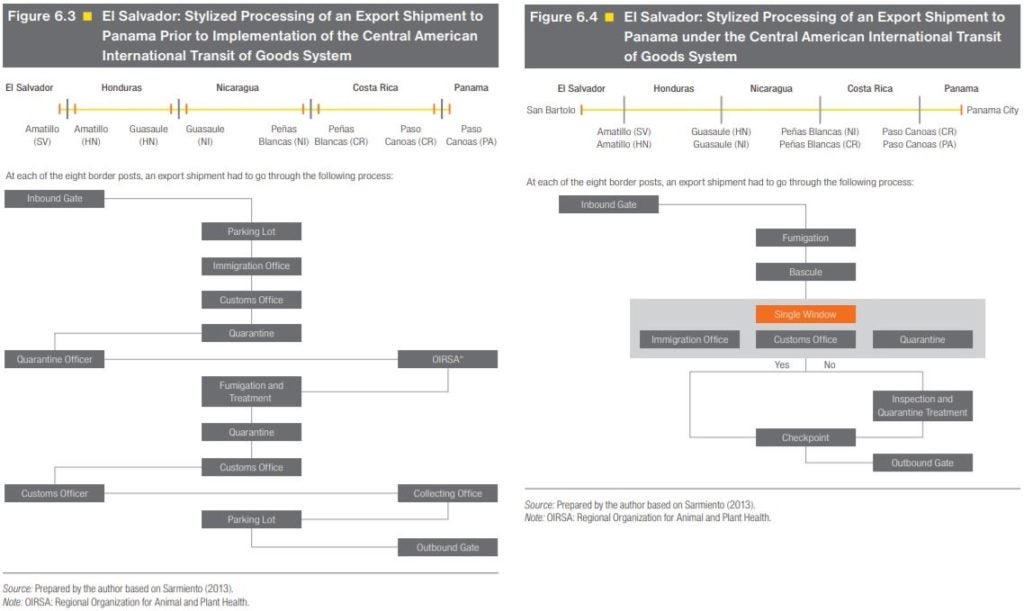

The TIM covers international transit between Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. Thanks to the system, central American exporters have gone from having to compile multiple copies of the same documentation, show up in person at customs facilities, and fill out entry and exit forms at immigration on both sides of border crossings to using a system with unified border controls and a single online form that is coordinated through all the agencies in question to allow real-time monitoring of the entire process. For example, under the previous system, a shipment from El Salvador to Panama had to go through 112 stages (14 stages at each of the 8 border crossings), while the same shipment under the TIM system only has to complete 28 stages (7 stages at 4 border crossing), which represents a 75% reduction in bureaucratic procedures (figure 1). Naturally, this new system has improved times at the border and has significantly facilitated the monitoring and management of shipments.

The TIM in action: How it has impacted El Salvador’s international trade

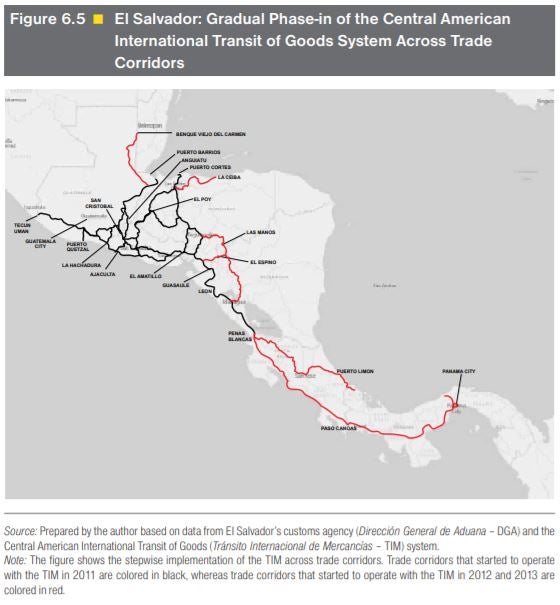

El Salvador was the first country to implement the TIM. The system was phased in gradually between 2011 and 2013 for international overland trade (see figure 1). By the end of 2013, the TIM included corridors (or origin–customs segments) that covered most of the country’s trade with Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. It is important to note that the most recent additions to this list of corridors are due to the implementation of the TIM in neighboring countries or the expansion of its coverage there (figure 2).

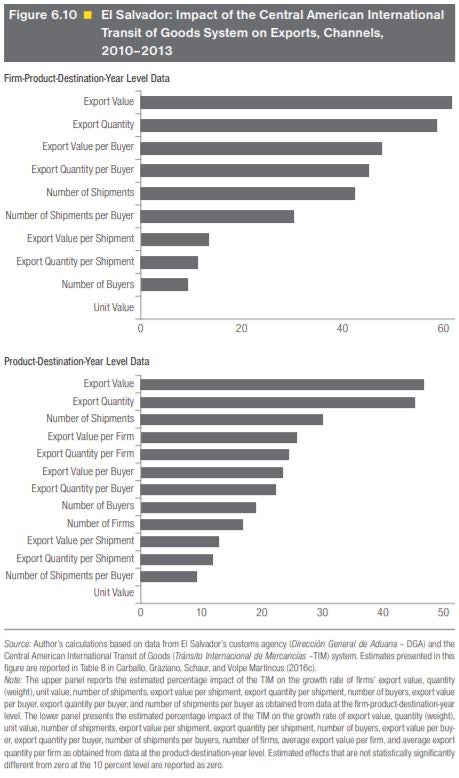

The implementation of an effective transit system would be expected to have a positive impact on international trade given the reduction in costs that such systems can bring about. Has this been the case with the TIM? The available evidence suggests that the rate of growth for exports from El Salvador via the TIM system has been 2.7 percentage points higher than for exports that did not use it. This additional growth is essentially explained by the relative increase in firms’ numbers of shipments (figure 3, upper panel) and to a lesser extent by the increase in the value exported per shipment. The TIM also seems to have contributed to increasing the number of exporter firms and enabling new firms to penetrate international markets (figure 3, lower panel).

In aggregate terms and controlling for the volume initially exported by the firms in question, Salvadoran exports would have been 6% lower if the TIM had not been implemented. With regard to the estimated cost of fully implementing the system, this translates into a cost/benefit ratio of US$40 for every US$1 invested in the TIM.

Lessons learned and international transit in the region

Transit systems can have a substantial effect on international trade, as the TIM experience has shown. The countries of Latin America could make the most of these experiences by moving toward implementing transit systems that allow them to take greater advantage of their export potential. The countries that particularly stand to benefit from acting on the lessons learned from the TIM experience in Central America include Ecuador and Colombia, which are carrying out pilot tests with the TIM, and member countries of the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), which have been implementing their own regional transit system. Finally, the region as a whole should be aiming to integrate the different subregional transit systems so as to achieve a more coordinated form of trade facilitation between countries.

Leave a Reply