To learn more about this issue, see chapter 5 of Out Of the Border Labyrinth, a report published by the IDB’s Integration and Trade Sector, and IDB Working Paper series no. IDB-WP-706, “The Border Labyrinth: Information Technologies and Trade in the Presence of Multiple Agencies.”

Paperwork at the Border: A Process or a Trial?

About a hundred years ago, Franz Kafka wrote:

Cases like this can last a long time […] the first documents submitted are sometimes not even read by the court. They simply put them with the other documents […] the first documents submitted are usually mislaid or lost completely, and even if they do keep them right to the end they are hardly read […] The trial would not be public, if the court deems it necessary it can be made public but there is no law that says it has to be. As a result, the accused and his defense don’t have access even to the court records […] and that means we generally don’t know—or at least not precisely—what the first documents need to be about, which means that if they do contain anything of relevance to the case it’s only by a lucky coincidence.

The circumstances under which firms that trade across borders operate do not differ markedly from these passages from Kafka’s famed novel The Trial. According to the Department of Homeland Security of the United States, “Today, traders must submit the same information to multiple agencies, multiple times through processes that are largely paper-based and manual.”[1]

For example, in Costa Rica, in addition to the national customs agency, there are a further 16 agencies that play a part in the export process. Until the mid-1990s, each of these agencies used different documents, which had to be submitted in person at offices scattered around the country’s capital, San José. Once processed, these documents had to be delivered, also in person, to the appropriate customs office. As a consequence, completing all the paperwork for the export process took at least five days but generally lasted much longer.

The above example reveals how, in the absence of efficient procedures and appropriate coordination, foreign trade-related administrative procedures may be repetitive and redundant and consequently generate high trade costs, especially when they are paper-based.

Redesigning the Border Process: Single Windows for Foreign Trade

Single windows for foreign trade (SWs) are one-stop institutional arrangements that streamline the administrative procedures for international trade transactions. They allow parties to present standardized information at a single point in order to comply with all regulatory requirements related to imports, exports, and the transit of goods.

Information technology and interoperability systems have enabled the development and implementation of electronic SWs. Rather than completing and physically taking paperwork from one office to the next, firms can use SWs to present all documentation online, and the different agencies and authorities can exchange digital documents and issue foreign trade–related permits.

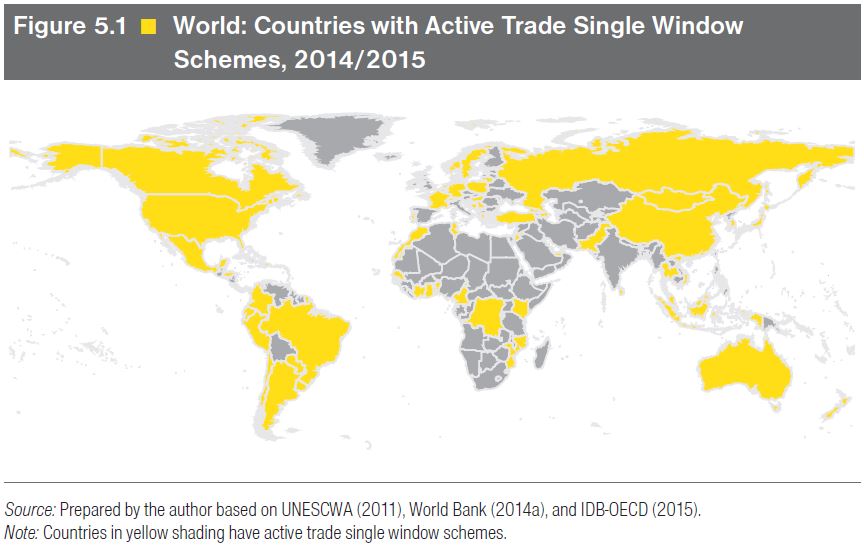

Over 70 countries around the world have already implemented SW schemes (figure 1)[2].

SWs mean that firms can interact with a virtual agency instead of having to go in person to different places to obtain paper forms, fill these in, and present them to the different regulatory bodies in question. SWs thus reduce the cost of paperwork, as firms can manage their commercial documents more efficiently and thus cut down on their administrative load. They also mean that information can be received and processed with greater speed, punctuality, and precision, making response times shorter.[3] These systems generally also allow each application to be tracked throughout the process, making decisions more predictable.

Streamlining the Border Process in Costa Rica: The Electronic SW system

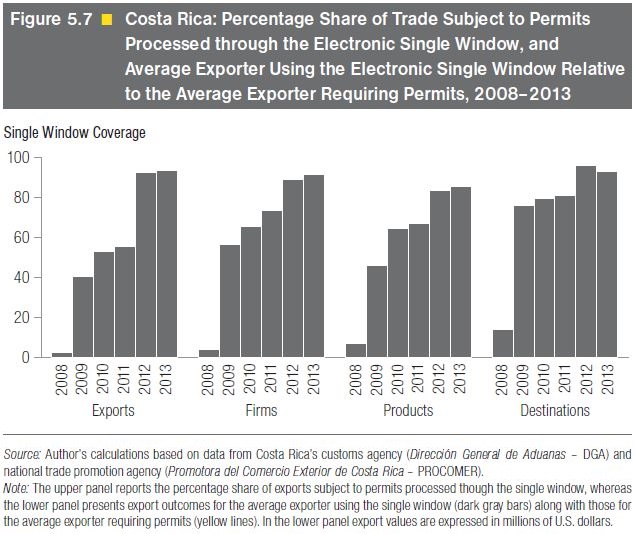

Costa Rica gradually adapted an electronic SW system between 2005 and 2010 (figure 2). From that point on, all that exporter firms need to do was to fill in a single form online once, which the system would then distribute automatically to the different agencies that needed to issue permits, according to the regulations. These permits were then sent electronically to the customs computing system to be attached to the respective customs declarations. The implementation of the SW scheme implied a change from a system whereby shipments requiring permits were processed manually and separately by each agency involved to one in which paperwork is processed electronically by all agencies at the same time.[4] As a result, firm representatives no longer need to go to different offices in person or send forms to each agency.

What Trade Gains Have Come with the Streamlining of the Border Process in Costa Rica through the SW System?

In theory, SWs reduce administrative obstacles and, specifically, waiting times, which may increase the frequency of shipments and thus of exports as a whole. But how far is this actually the case? The evidence for Costa Rica suggests that the adoption of the SW system was associated with increased export growth: exports processed through the SW system grew 1.4 percentage points more than exports that were subject to non-electronic processing. This increase in exports may be attributed to more frequent shipments, a more diverse set of buyers, and greater sales volumes per buyer.

Without the SW system, aggregate Costa Rican exports would have been, on average, 2% lower than they in fact were between 2008 and 2013, which is equivalent to approximately 0.5% of the country’s total GDP. Given these trade gains and the costs involved, the benefit/cost relationship for the SW system has been approximately US$16 for each US$1 spent on it.[5]

Firms with Greater “Administrative Needs” and in Unfavorable Geographic Conditions Benefit more from this Simplified Process

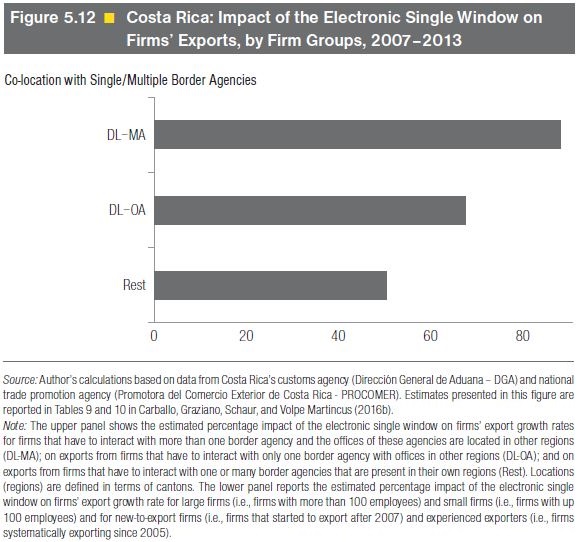

The SW system had the greatest impact on firms that are located in regions where the agencies that issue the required permits do not have branches and whose export portfolios implied that they must obtain permits from multiple public agencies (figure 3). These firms have made the greatest savings in terms of the costs and times that were involved in visiting the offices in question thanks to the reduced geographic restrictions allowed for by the online interface.

The Future of the Process in the Region

Up to now, most countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have, in the best-case scenario, an online system through which firms can submit their customs declarations and request permits through two different points of entry—the customs information system and the information system shared by other border agencies. Communication between these systems regarding shipments’ documentary processing is more automatic in some cases than in others. Countries in the region should integrate and automate these systems and, ideally, work toward establishing a single point of entry where firms can complete all relevant foreign trade procedures for all the border agencies involved, as some countries in Asia have already done (for example, Japan, Korea, and Singapore).

Likewise, the countries of Latin American and the Caribbean should start to take steps toward the next stage: internationally interoperable SW systems and regional initiatives to connect and integrate national SWs, like the one already being implemented by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, which will allow information and relevant commercial documentation to be exchanged across borders.

Leave a Reply