| To learn more about this issue, see chapter 1 of Out Of the Border Labyrinth, a report published by the IDB’s Integration and Trade Sector, and IDB Working Paper series no. IDB-WP-782, Endogenous Border Times. |

|---|

In recent years, various indicators have been developed to measure time at the border. In general, these measures are based on surveys of international freight transportation companies and are one-dimensional, which is to say that they reflect a single value for each country.

Current measures of time at the border

The best-known indicators are: (1) the number of days it takes to trade across borders from the Doing Business (DB) index and (2) the Logistics Performance Index (LPI), both of which are published by the World Bank. The latest issue of the DB reports on internal transportation times and the time needed to comply with paperwork and other formalities at the border. The LPI reports on the time it takes for goods to go from the supplier’s factory to the port/airport or the buyer’s warehouse, in the case of exports, and vice versa for imports. It also reports on customs release times, whether or not the shipments in question are subject to physical inspections, and the proportion of shipments that this applies to.

These indicators are a valuable initial attempt to measure these factors and are undoubtedly useful as an initial practical approximation as they cover a broad range of countries and allow time at the border to be monitored over the years.

However, these indicators have their limitations

These are mainly to do with coverage and the assumptions that underlie these surveys, which affect their precision. Another shortcoming is that these measurements do not contemplate the significant disparities in time to trade within each country. This is important as time at the border can vary greatly, which may have a significant effect on firms’ trade outcomes.[1]

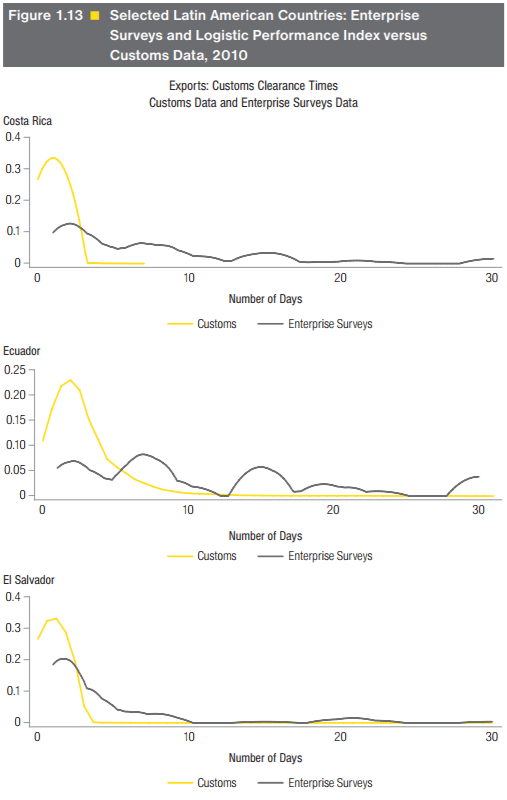

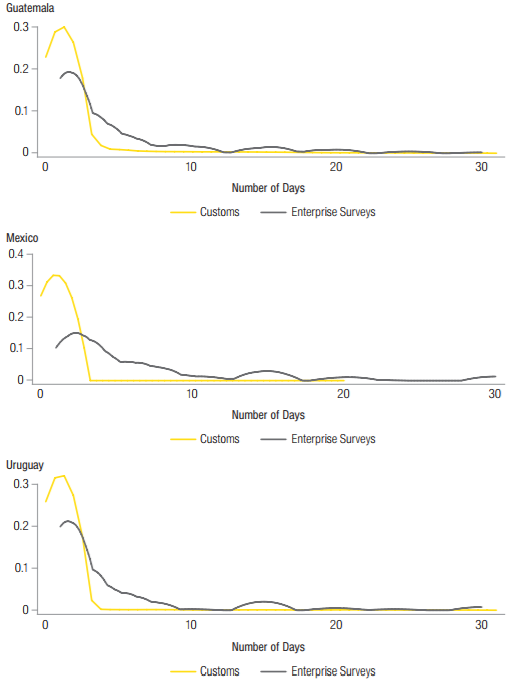

The World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys constitute an initial approach to this heterogeneity on the export side, as they include a firm-specific measure of time at the border for the customs stage. This data reports the average number of days between goods from a certain establishment reaching their exit point and these goods being released by customs.

Transactional customs data is a significant advance in measurement terms

In several countries in the world, customs and other border organizations systematically gather highly detailed, transaction-specific, real-time information on the start and finish times for border procedures. This allows time at the border to be described exhaustively and precisely for the entire universe of shipments that enter or leave an economy, rather than a mere sample of these. When big data from customs information systems is used to compare distributions of the number of days taken to release exports from customs with the corresponding data from the World Bank Export Surveys, the latter tend to underrepresent shorter dispatch times and overrepresent longer ones. Consequently, they systematically overestimate customs processing times (figure 1).

The devil is in the details

Customs declarations and electronic cargo manifests report the arrival date of the shipment, the date that it was unloaded, the date that the customs import declaration was created and recorded, the customs processing channel, the date of physical inspection, where relevant, and the date that the shipment was released from customs.

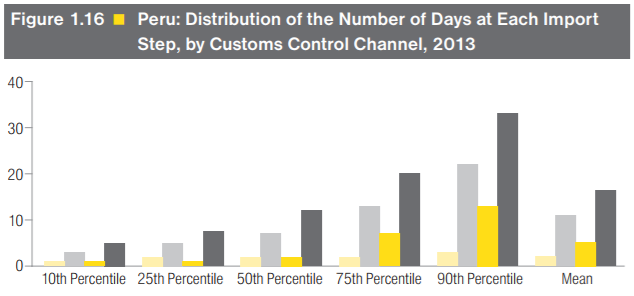

An analysis of this data for Peru reveals four stylized facts.

Fact 1: Total time at the border includes port and customs processing times, and storage time and preparation between each of these stages (and after them).

Fact 2: Entry times are highly skewed toward fast clearance times but there is a long tail of slow clearances. Nearly 50% of shipments complete the process within 12 days or less but may take more than 30 days to do so at the higher end of the distribution. Median total time at the border is 12 days (figure 2).

Fact 3: Entry times vary by country of origin, products, and exporting, and especially importing firms.

Fact 4: Firms absorb long unloading times with shorter storage and preparation times. In other words, firms’ buffer times are a response to the times that ports take to handle shipments. Specifically, firms cut down on preparation and storage time by 1.5% for each 10% increase in the time it takes for port operations to be completed. According to data for 2013, the median time that goods spend at the port is 48 hours and the median storage and preparation time is 168 hours, so firms reduce the latter by two and a half hours for each five-hour increase to the former. Although real port and customs processing times are uncertain and extending shipment deadlines is costly, firms balance out the cost of that additional time and the cost of a late delivery when they decide what time margin to assign to the stage in the supply chain that takes place at the border.

The above evidence has two clear implications for measuring time at the border

First, the times at the border that are relevant to policy-making can be measured more precisely if the real processing times associated with port and customs handling are used. The total time that shipments spend at the border may differ from this figure because firms include a margin of time to avoid late deliveries. Combining processing-related measures with measures that depend on firm behavior may thus give rise to country rankings that are not entirely consistent if they are assumed to reflect the efficiency of ports or customs services.

Second, access to information on the distributions of times at the border is essential to understanding critical heterogeneities within countries, as these times vary by product, origin, and importer. If this information is not considered, country-level measures may be influenced by the set of goods that a given country trades, its trade partners, and the specific characteristics of its firms. Therefore, variations in these measures between countries may not necessarily reflect differences in the efficiency of their respective port and customs organizations.

This measurement affects estimates of the effects of border times and evaluations of the impact of trade facilitation policies

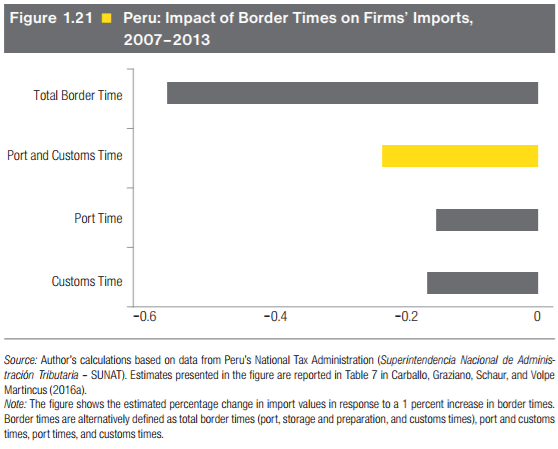

If these are measured using port and customs processing time, times at the border have a significant negative impact on imports. Specifically, it is estimated that a 10% increase in time at the border reduces imports by 2.4%. However, this effect would be 5.7% if it were based on total time at the border (figure 3). This shows that measures of total time to trade that include shares that can be attributed to firms’ optimizing behavior may lead to biased estimates of the cost of times at the border.

To summarize, the transactional data on the processing of trade flows that is gathered by border agencies allow times at the border to be measured and reported for a broad set of countries. These could then be ranked and monitored over time by applying measurement criteria such as those used in the World Customs Organization (WCO) time release study, including rules for calculating summary measures that reflect the distributions of these times. When evaluating investments in trade facilitation, the focus needs to be on the share of time at the border that is connected to the necessary processing of shipments, which can then be used in estimates of the costs that these times represent.

[1] For example, the standardized case study on which the DB’s data collection process is based starts with the premise that each economy imports a shipment of 15 metric tons of auto-parts in a container from its main import partner and exports its main export product to its main export partner via the most widely used form of transportation. According to trade data for the last five years, the benchmark imports and exports for measuring time at the border in Uruguay are exports of meat and meat offal to the Russian Federation through the port of Montevideo and imports of motor vehicle parts and accessories from Brazil through the Río Branco border crossing. The former account for 2% of total export values and 1.5% of the total number of exporting firms, while the latter only represent 0.1% of total import values and 0.2% of importing firms. Consequently, the corresponding time indicators could hardly be considered representative of Uruguay’s foreign trade.

Making border crossing more efficient and less costly should be an item in any countries agenda but I wouldn’t sacrifice security for faster transactions.