This blog was initially written by Edin Noé López and published in 2020. The text was updated by Lucía Rios Bellagamba and Daniela Brenes in 2024.

New Frontiers: AI and Indigenous Peoples

What is the link between generative artificial intelligence (AI) and the Indigenous Peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean? Technology is affecting all areas of our society, and the cultures and languages of Indigenous peoples are no exception.

A UNESCO report highlights how the advancement of AI requires greater social inclusion but has the potential to benefit the Indigenous Peoples of our region. The report states: “We can envision a participatory AI rich in cultural perspectives; (…) respectful of human knowledge and experiences; enhancing sustainable development and promoting fundamental freedoms.”

An example of this potential is how large language models (LLMs) have expanded the possibilities of preserving and reproducing Indigenous languages.

In Peru, the National University of San Marcos created Illariy, an artificial intelligence avatar that teaches Quechua. This project uses OpenAI’s ChatGPT technology and is the first customized model generated in an indigenous language available in the GPT Store.

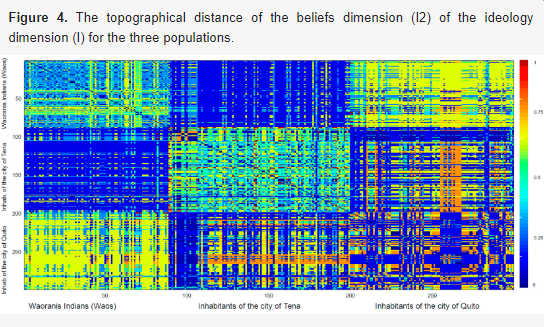

Artificial intelligence can also be used to analyze population characteristics. In Ecuador, researchers from the University of Alicante in Spain and the Central University of Ecuador used machine learning and the Atlas.ti tool to identify “degrees of Indigenous identification.” By analyzing 299 interviews, they were able to map and quantify characteristics of Indigenous identity in two cities (Quito and Tena) and three communities of the Waorani nation (Konipre, Menipare, and Gareno).

Like Water and Oil?

It is common to hear that technology and Indigenous Peoples are incompatible, but this is just a myth. On one side, these are peoples with millennia-old technologies, which are underestimated by the widespread perception that they do not use the so-called new Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). However, there are more and more communities that are appropriating cell phones, WhatsApp, social networks, and the Internet, not only to communicate or learn new knowledge but also to reaffirm their own. Who has not seen, for example, an Indigenous woman on the bus or in the market with her cell phone in hand, speaking in her own language with no difficulty at all? It is not true, then, that technology and Indigenous Peoples are like water and oil.

Indigenous Memes?: What Happens When Indigenous Peoples Make Technology Their Own

When delving into Indigenous communities, it is not surprising to find young people discussing encounters on Facebook or another social network. Some memes are already being shared in Indigenous languages, albeit very slowly, on these social networks. In Guatemala, for example, there are some memes and jokes in the Q’eqchi Maya language. It is equally interesting to see how art supported by ICTs becomes a vehicle to vitalize and/or recover Indigenous language and knowledge.

YouTube has also become an important global space where young artists sing in Indigenous languages. It is modern rhythms like rap and rock that attract rural and Indigenous youth today. Peru, Mexico, Chile, and Guatemala are examples of this; even some of these young Indigenous artists have been able to appear in mass traditional media such as radio and television.

Movies dubbed into Quechua in Peru are another example of how the Indigenous language becomes important and valid in spaces where it had never been. Art fused with technology can be the answer for these youths, who increasingly recognize themselves as Indigenous, to have a space to use their language without being judged for incorrect grammatical use, pronunciation, or writing, as it, unfortunately, happens in school.

Technology for Conservation?

In a reality where languages are lost every day, along with ancestral knowledge, it is imperative to take innovative actions and prioritize use over form. Today, it is up to the school to learn from Indigenous youth and the spaces they are gaining every day with the use of technology.

In the latest censuses of several countries in Latin America, there was an increase in the Indigenous population by self-identification. Furthermore, these populations that historically were considered rural are now also, and sometimes predominantly, in urban areas. These changes should be a wake-up call for ministries of education. Policies, programs, and projects should be designed and implemented to strengthen and revitalize Indigenous cultures and languages by resorting to the languages, media, and technologies preferred by today’s youth. In the educational realm, it is essential for these ministries to develop actions to rethink Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE), also relying on technology. Tecnology and IBE should not be seen as water and oil. On the contrary.

Innovative Use of Technology with Indigenous Languages

Currently, throughout the educational trajectory, it can be evidenced that Indigenous people disappear in the system; in pre-primary and primary school, they are still identified, although they decrease year by year according to school censuses; in secondary school, they are much fewer, and in university, it is usual for them to disappear due to the homogenization that it does of its student population. Therefore, although there are few experiences of ICTs and IBE, it is worth recovering them and scaling those that have responded to the changes of the 21st century.

Among the experiences of innovative use of technology, we can mention:

- Researchers from the Technological Institute of Oaxaca created a mobile app that allows interactive learning of Mixtec languages with the support of artificial intelligence.

- The Woolaroo app, developed by Google Arts & Culture, uses object recognition through cell phone cameras to indicate their name in endangered Indigenous languages.

- With the support of the National Institute of Indigenous Languages of Mexico, in 2022, Maya (currently spoken by 795,500 people) and Tepehua (used by about 10,400 people) languages were added.

- Google Translate integrated Quechua and Aymara in 2022.

- ChatGPT offers translations and basic text writing in multiple Indigenous languages, such as some variations of the Maya language, Guarani, Nahuatl, among others. However, the quality of the content depends on the availability of material in this language on the web, the context, and the complexity of the requests.

- If you want to experiment with this tool, you can ask for a “confidence parameter” of the translation in the prompt you insert in the platform.

- FUNPROEIB Andes has produced videos and audio for the revitalization of the Uru language and culture in Bolivia.

- The App for learning five native languages in Bolivia was designed by the Organization of Ibero-American States.

- The translation into Quechua of Windows and Office for Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. The WujApp application for learning Kaqchiquel in Guatemala. T

- The experience of the Sesteadero Educational Institution, in Colombia, where young people produce photos and videos about fauna and their local reality that they upload to social networks.

The Potential of AI and ICTs in Indigenous Peoples’ Education

Indigenous People are not only using technology but also technology is already “learning” from the available content about Indigenous peoples on the web. We need to overcome erroneous stereotypes, democratize access, and take advantage of technological advances as a conservation and learning tool.

It is urgent to reflect on bilingual intercultural education and youth cultures in rural and urban areas; prioritize the use over the form of native languages in school spaces; and inquire about the use of language in non-school spaces to find answers that can be adapted to the school environment, and above all, create spaces for children and young people to share their culture through their language and thus strengthen their self-esteem.

Leave a Reply