As 2019 draws to a close, Latin America and the Caribbean faces at least four big challenges. First, growth this year is well below potential. Second, potential growth is low. Third, the region remains subject to large shocks. And fourth, despite recent gains, inequality remains high and aspirations are outstripping the meagre outlook, contributing to protests across the region that are questioning the very nature of economic systems.

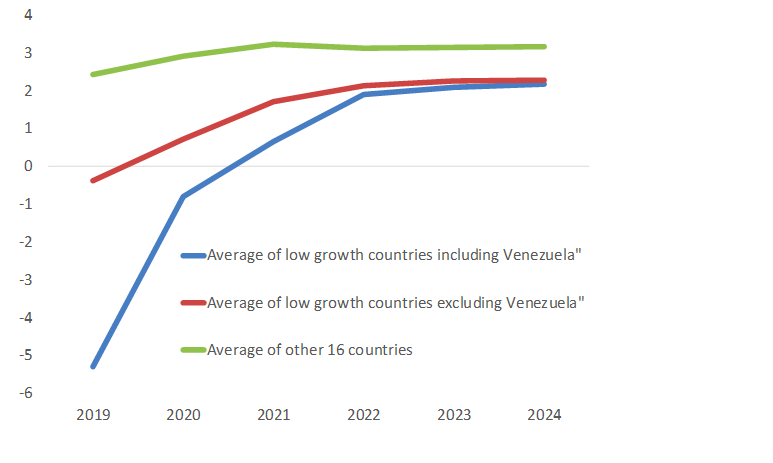

Analyzing the growth projections from the IMF’s October 2019 World Economic Outlook, which estimates close to zero growth for the region for 2019, it’s clear that the projected recovery stems from assumptions about how a few countries with low or negative growth, will return to their potential. To illustrate, the graph below separates eight low or negative growth countries (Argentina, Barbados, Brazil, Ecuador, Haiti, Nicaragua, Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela) from the other 16 borrowing member countries of the IDB that are growing at rates relatively close to their estimated potential. If the projected recovery happens next year, it will come from countries getting closer to their potential and not from projected increases in potential growth rates.

Figure 1: Latin America and the Caribbean’s projected recovery

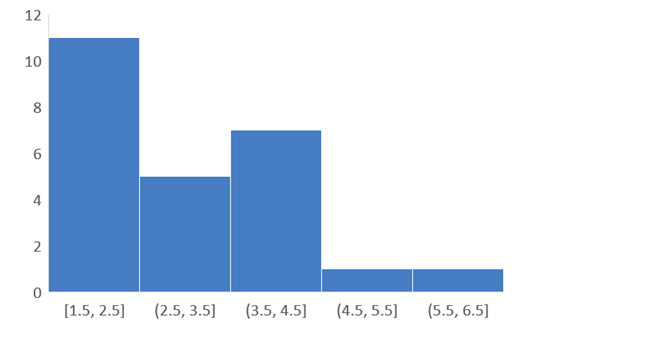

This introduces the second problem, namely that potential growth remains low. While the region has benefitted from strong demographics, investment and investment efficiency have been low. Looking at the period 1960-2018, the increase in the labor force boosted growth by 0.6% per annum, and improvements in skills boosted it by 0.9% per annum, but increases in capital raised growth by only 0.3% per annum, while other sources of productivity (or “investment efficiency”) did not increase growth at all. These figures are sample dependent and taking out the 1980’s (the lost decade) does improve things somewhat, but the overall message remains. What does this mean looking forward? The demographic bonus is waning and estimates of countries’ potential growth do not look so great. Most countries in the region have estimated potential growth of between 1.5% and 2.5%, and only two have estimated potential growth of greater than 4.5% – see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Potential Growth Remains Low

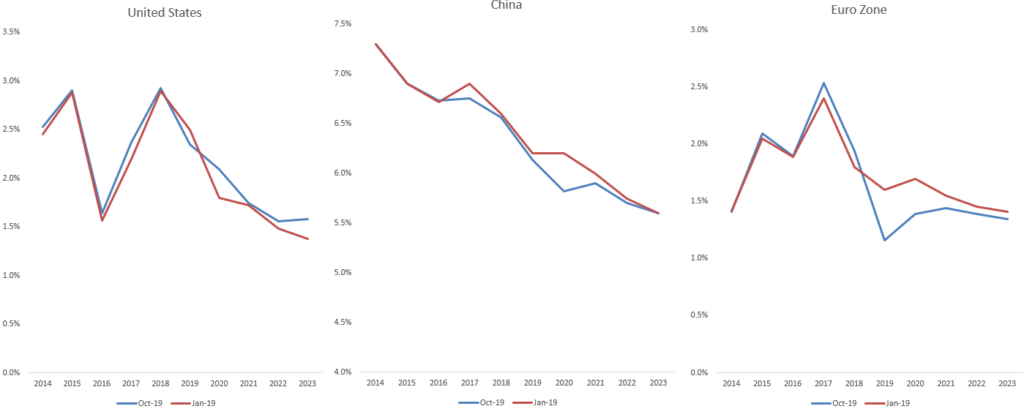

Output gaps (growth below potential) are large, currently due to both domestic and external shocks. Global growth trends also reveal cause for concern. Chinese, Eurozone and U.S. growth rates have been falling, and that trend is broadly expected to continue.[1] A balanced global recovery has turned into systemic slippage with growth affected by trade tensions and heightened policy uncertainty: World manufacturing is in recession. Between January and October 2019, there were downgrades for expected growth in the case of China and the Eurozone, and a slight decrease in 2019 U.S. growth, but expectations for the US in 2020 were slightly improved- see Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: China, Eurozone and US Growth Projections

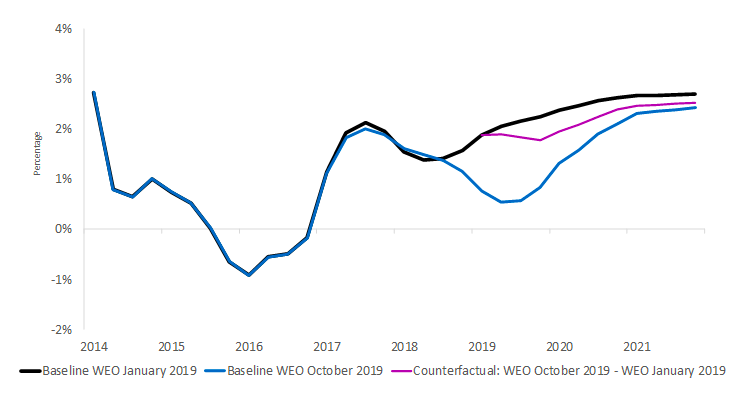

Could these changes account for the slowdown in Latin America and the Caribbean? In Figure 4, projections as of January 2019 (the black line) are compared to projections as of October 2019 – the blue line. The third (purple) line in the graph is an estimate of the impact of the changes in growth expectations in Latin America and the Caribbean caused by the changed growth forecasts for China, the Eurozone and the US employing a statistical model of the world economy.[2]As can be seen, there is a negative impact, but the estimated effect on the region is relatively small. The difference between this estimate and the October 2019 baseline is then due to other factors, including more domestic ones, with the recession in Argentina and the slowdown in Brazil and Mexico playing a role as significant contributing factors that are not explained well by these global developments.[3]

Figure 4. Latin American and Caribbean Growth Projections as of Jan 2019 and Oct 2019 and a Counterfactual Incorporating External Shocks

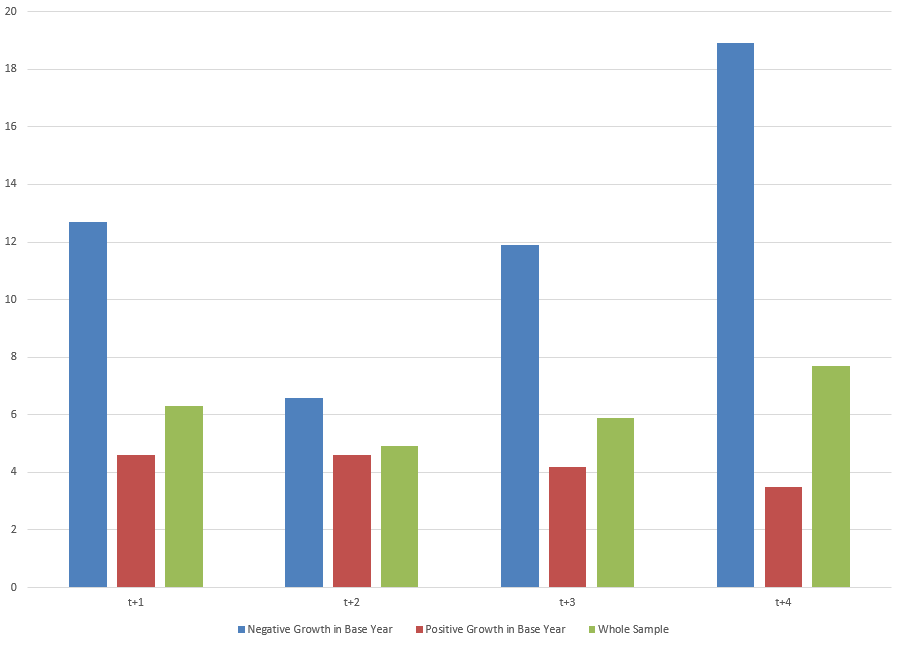

As a slight aside, the October 2019 World Economic Outlook indicates that growth will be 3.4% in 2020 as opposed to the 3.0% of 2019. How does the world recover if China, the Eurozone and the U.S. are still expected to slow? The answer, in a somewhat similar vein to Latin America and the Caribbean, is that a group of “stressed economies” are expected to become less stressed and three low growing and larger emerging economies (Brazil, Mexico and Russia) are projected to recover. As the IMF rightly points out, such projections should be considered as subject to potentially large forecast errors. An analysis of growth forecast errors reveals that, when growth in the base year (i.e.: the year when the projection is being made) is negative, those errors are much higher than when base-year growth is positive – see Figure 5. Moreover, when we consider the errors on growth projections four years out, the errors diminish if base year growth is positive, but they rise when base year growth is negative. The uncertainty attached to the projected global recovery is then very high as it depends critically on higher growth in economies that are in recession or have low growth currently.

Figure 5. Growth Forecast Errors When Base Year Growth is Positive or Negative

Finally, its notable that while protests have gripped the region, inequality has actually been falling. In particular, wage inequality, the major determinant of overall income inequality, has fallen and the rise in low wages appears to have been a particularly important contributing factor. Moreover, estimates of the percentage of the population that are “middle class” have risen. While inequality remains high, it seems impossible to explain what is going on in the region by just looking at recent trends in the movement in inequality or poverty.

It’s likely that recent protests are driven by multiple causes. They have certainly included many different groups with a variety of concerns. One additional, surely partial explanation might be a growing gap between aspirations and the current challenging outlook. An interesting conclusion of Beyond Facts: Understanding the Quality of Life, the IDB’s 2008 Flagship, is that the relationship between the satisfaction with specific services (and life in general) on the one hand, and with objective indicators, like service quality and income on the other, is not so straightforward. If people don’t see how things will improve as they look to the future, they may become highly dissatisfied, despite the fact that objective measures of quality may have improved. This analysis also suggests that actively involving people in decision-making at the district, city, workplace or school level can have a material impact on life satisfaction, over and above any change in objective indicators.

To conclude, the outlook for the global economy is particularly uncertain, and Latin America and the Caribbean should work to close output gaps, boost underlying potential growth and consider how to enhance protection from outside shocks. Inequality and poverty remain high but they were falling. Still, given current low growth, these gains are stagnating, and the gap between aspirations and realistic forecasts for objective indicators has widened. The coming years will be very challenging for policy makers. There is an urgent need to boost inclusive growth and ease citizens’ dissatisfaction, the subject of the 2020 Latin American and Caribbean Macroeconomic Report, to be published in March.

Editorial Note: Blog is based on a presentation at the World Bank – Inter-American Development Bank panel at the 2019 LACEA Conference in Puebla

Notes:

[1]The Eurozone is expected to recover somewhat in 2020 and 2021 but thereafter slow once again.

[2]The model is a Global Vector Auto-Regression model (or G-VAR), see the 2019 Latin American and the Caribbean Macroeconomic Report for further details.

[3]Having said that, policy uncertainty stemming from outside the region but affecting the region over and above the impacts on China, the Eurozone and the U.S. may not be well-reflected in the model.

Leave a Reply