Bunny Colvin, the policeman who invents Hamsterdam to alleviate the effects of drug trafficking in the imaginary Baltimore of the “The Wire,” appears in the fourth season of the series as a mediator who is trying to save some of the corner boys in the schools. Colvin ends up disappointed at how little education can do to avert those boys’ self-fulfilling prophecy. Fortunately, Latin America and the Caribbean is far from the Baltimore neighborhoods portrayed in “The Wire.” Education and intervention programs in the region show that, in the long term, harmful intergenerational dynamics can be broken. However, we still have a long way to go to achieve inclusive societies that provide opportunities for all, regardless of their socio-economic origin, race, ethnicity, or gender.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, persistent high levels of income inequality throughout most of the 20th century have been accompanied by low intergenerational mobility. Improving socioeconomic status from one generation to the next can mitigate extreme inequality, as mobility is considered essential for equal opportunities.

Social Mobility in Latin America and the Caribbean is Low

In The Inequality Crisis, we examine patterns of social mobility in the region and in comparison to the world through the lens of educational mobility. The data come from the World Bank’s database on intergenerational mobility presented in the Fair Progress? Economic Mobility across Generations around the World, which analyzes trends in intergenerational mobility using the 1980 cohort.

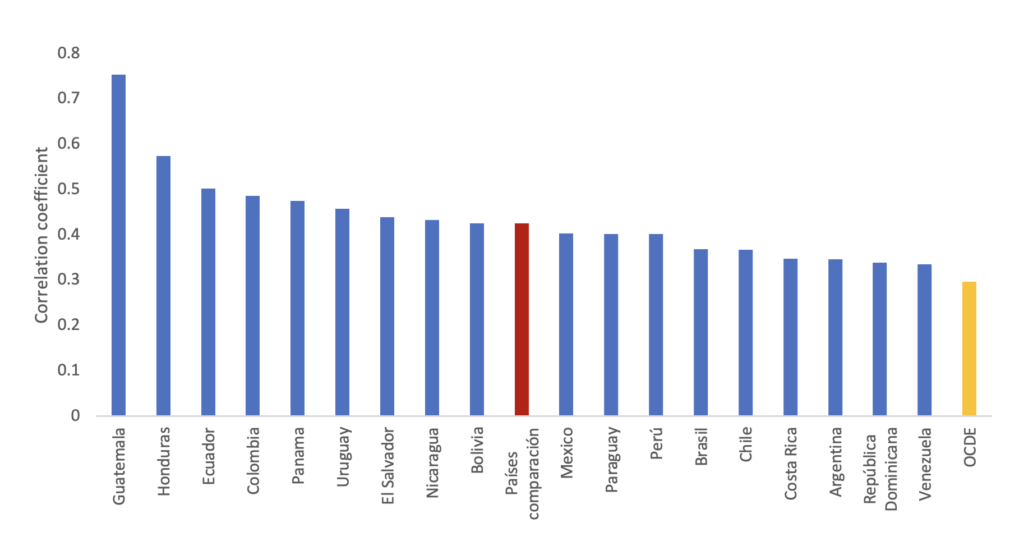

We use intergenerational persistence (IP) as the main measure. This measure is estimated using years of schooling (of parents and children) as the variable, constructed with the microdata of each country. A high correlation coefficient means that children with a high educational level tend to have parents with a high educational level, while a value close to zero means that there is no relationship between the education level of the parents and the children.

Figure 1 shows the intergenerational educational persistence for the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, the average of OECD countries, and the average of countries whose level of development is similar to that of the region. The average country in the region has a correlation of 0.44, higher than the OECD average of 0.29, and where countries with more intergenerational mobility have a coefficient of 0.19. This significant persistence occurs despite the fact that the region has made great strides in increasing access to schooling for families with fewer resources. In fact, educational inequality has declined steadily over the past decades in most of the countries of the region.

Figure 1. Relative Intergenerational Educational Persistence: Correlation Coefficient of Children’s and Parents’ Years of Schooling

Source: Busso, Matías and Julián Messina. 2020. The Inequality Crisis: Latin America and the Caribbean at the Crossroads. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.18235/0002629.

The graph shows that not all countries are the same: The least mobile (such as Honduras and Guatemala) have correlation coefficients above 0.5, while the most mobile (such as Argentina and the Dominican Republic) have coefficients below 0.35. It is important to note that, although the intergenerational correlation coefficients for education in the region are higher than in developed countries, they are not so different from those observed in countries with a similar level of development (comparison countries in the graph).

The Impact of the Environment Where People Grow Up

If we go back to “The Wire” as a metaphor, we see that it also underscores the importance of where you live. All the series’ protagonists know that, if you are born on the west side of Baltimore, there is little you can do to get out. The intuition of the series is not too far from reality. For the United States, researchers have found that the probability that a person born in the bottom quintile of the national income distribution will reach the top quintile in adulthood is just over 4% in some urban areas and near 13% in others. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the scientific literature is more incipient, but it is difficult to think that geographic heterogeneity does not play an important role in the development of inequality and shape social mobility between different generations. A very significant characteristic of low mobility areas in this literature is residential segregation by income.

This residential segregation by geography is often accompanied by segregation in the quality of public services. That is, certain areas or regions have better quality schools or hospitals than other areas. For example, causal estimates for the United States show that each additional year of life in a county that offers greater opportunities results in a 0.5% increase in income in adulthood. These effects are less apparent in counties with higher income inequality and worse schools, and the negative effects of high residential segregation are notably stronger among boys than girls.

In addition to affecting present inequality, recent research has shown that urban segregation can also affect future inequality. Much of the most compelling evidence on the effect of neighborhood characteristics on economic and social mobility comes from experiments conducted in housing programs in the United States. The best known is Moving to Opportunities (MTO), a large-scale program carried out in five cities in the mid-1990s. MTO provided housing vouchers to randomly selected families so they could move from public housing projects to higher-income neighborhoods. The initial studies on MTO found few short-term effects. However, more recent research has found strong positive long-term effects on college enrollment, income, and the frequency of single mothers and fathers among people who moved to another neighborhood in the city while they were children.

Privatized Services Worsen Poverty Traps

Similar studies on the geographical dimension of intergenerational mobility are still hard to come by in the countries of the region. However, there are studies showing the high degree of segmentation that exists. For example, in our report, we found that, on the geographical side of segregation, the differences between neighborhoods are what most explains inequality in Brazil. On the education side, families with higher incomes tend to privatize this service, which is why education in the region is segmented, with Chile and Peru being the countries with the highest rates. These segmentations exacerbate the problem of social mobility and can create poverty traps in segregated neighborhoods. Future research like the efforts mentioned could help us understand and search for mechanisms that provide better opportunities, equality, and social mobility. In Latin America and the Caribbean, inequality regarding education and the geographical dimension of intergenerational mobility are challenges where some slight progress has been made over the last two decades. Much remains to be done, but international evidence suggests that ambitious intervention programs can prevent the region from resembling the part of Baltimore shown in “The Wire.”

Leave a Reply