In recent days, climate change has surged back into public consciousness with a disturbing report of rapid melting in the West Antarctic ice sheet. According to the report, the disintegration of the massive block of ice, larger than Mexico, could combine with other ice melts to raise sea levels by as much as six feet by the end of the century. That could eventually threaten cities from New York to Venice. It could also trigger mass migrations.

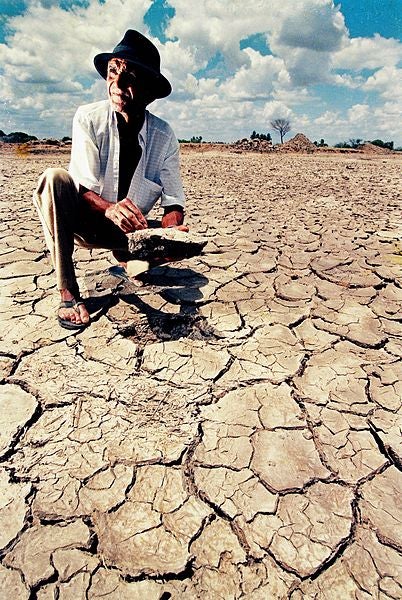

Climate change, of course, already is upon us. Over the last two years, soaring temperatures and searing drought in Colombia and Venezuela have killed tens of thousands of wild and domestic animals, triggered crop failures, and left municipalities without drinking water or irrigation. Drought around Sao Paulo, Brazil’s largest city, has reduced hydroelectric output and hampered industrial and agricultural production. Rains and floods have pummeled large areas of Central America and the Caribbean.

But as the impacts accumulate, many parts of the world, including Latin America and the Caribbean, seem unprepared for the scale of the challenges that lie ahead. That is not only the case when it comes to adaptation measures, like building protective seawalls against rising oceans, better drainage for floods, or more efficient irrigation to combat drought. It also is true when it comes to building smarter, more sustainable cities with better housing and more efficient transport to reduce emissions and receive migrants as climate change worsens.

An IDB study by Omar O. Chisari and Sebastián Miller focuses on what we can expect in Latin America. According to the study, as large numbers of people descend on large cities they will begin to earn higher wages. They will consume more goods, use more appliances, and increasingly utilize public transport. That will cause an increase in carbon emissions, above and beyond the increases to be expected from economic growth. And it will force countries, just now developing mitigation measures to meet their carbon reduction targets, to impose more carbon taxes to reign in growing emissions in the industrial and other sectors.

On the economic level, meanwhile, wages will rise somewhat for migrants compared to what they earned in their places of origin. But they will fall for everyone else, including the poor, as the oversupply of labor takes effect. Rents will increase, and urban sprawl will grow more severe as the migrants move into available areas in the outskirts of the cities, generating greater traffic and congestion.

Health and education services will be ever more stressed, and only in part because of the additional population flows to cities. As another IDB study emphasizes, natural disasters can affect infants and children in utero, leading to long-term impacts in depression, anxiety and educational attainment which are even passed on to the next generation. That means health and education systems will have a dual challenge in attending to ever greater numbers of people and dealing with a whole new population of people traumatized by climate-related storms, floods, and droughts.

Migration and its traumas, are, of course, hardly new to Latin America. Migration from Europe in the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries transformed immigrants and their descendants into dominant sectors of the population in numerous countries. Then, after World War II, massive population shifts from the countryside to the cities made Latin America one of the world’s most urbanized regions. But climate change is expected to accelerate urbanization, with 10 to 15 percent of the total population migrating from rural areas to cities between 2015-2050. As people seek out places that are better prepared and less vulnerable to climate shocks, internal movements, such as those from Brazil’s rural areas to Sao Paulo, will increase. And so will movements from rural and urban areas in poorer countries to major metropolises in wealthier ones. There will, for example, be more people moving from Brazil’s neighbors to its big cities; from Paraguay and Bolivia to Buenos Aires, and from Central America to Mexico City.

The issue is not how to stop that migration, but how to better absorb it. The IDB’s has long pushed for Sustainable Cities. The initiative, in the climate change context, becomes critical. Latin America, among other things, will have to build better low income housing, which is better insulated for energy efficiency and more centrally located so that long commutes don’t increase carbon emissions. It will have to move to more climate-friendly transportation, like buses run on natural gas or electricity-powered light rail. It will have improve the bureaucracy for migrants so that they can pay taxes, receive social security and become integrated into the society. And it will have to improve the health and education systems so they can absorb people from different cultures and backgrounds. If ever more severe impacts from climate change are inevitable, so are migration and growing urbanization. The only real question is whether Latin America can rise to the challenge.

Leave a Reply