Covid-19 has wreaked havoc in Latin America and the Caribbean. It has killed hundreds of thousands of people, destroyed livelihoods and is provoking a deep economic crisis. The New Year is a good time to take stock and try to understand the economics of the crisis. The new year may start with a hangover: The response to the crisis may leave three issues overhanging. In this blog I outline six basic facts, discuss three risks that overhang the recovery, and raise two questions critical for the coming months. The discussion draws on ongoing work to be developed and published in the 2021 Latin American and Caribbean Macroeconomic Report, scheduled for publication in March.

- GDP has plummeted

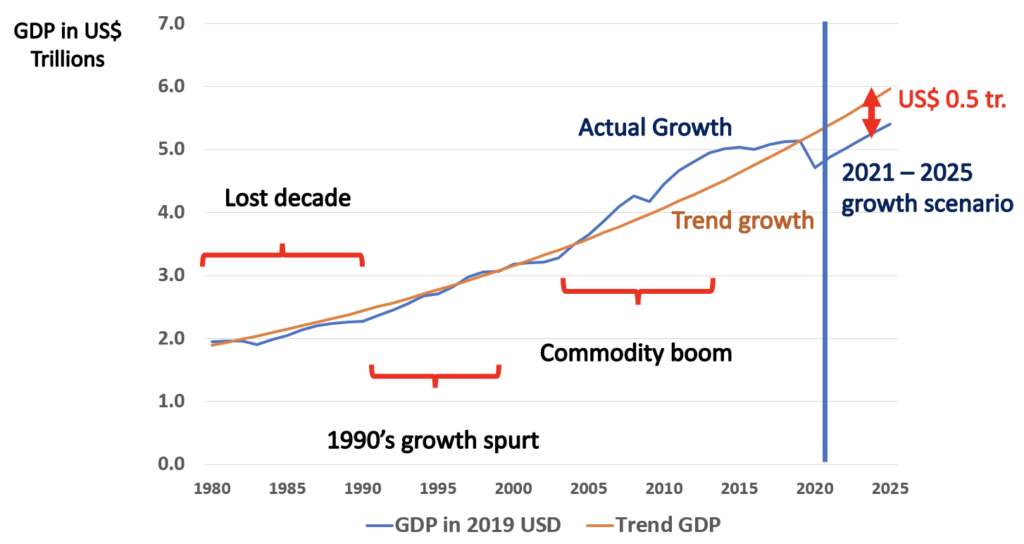

GDP dropped by more than 8% in 2020, and for a quarter of IDB borrowing countries, it has dropped more than 10%.[1] The region’s GDP was more than US$5 trillion in 2019. But relative to the long-term average, growth rate of 2.5%, this represents a loss of over a half a trillion dollars of GDP this year. This is no ordinary recession. It was largely self-imposed to slow the spread of the virus. The IMF expects a rebound in 2021 with 3.6% growth, which will then revert to trend. In that scenario, however, we will never regain the half a trillion dollars – Figure 1. GDP per capita in the region is expected to fall from $16,000 in 2019 to $14,800 in 2020, with large disparities between countries and with significant increases in inequality within nations.[2]

Figure 1: Latin America and the Caribbean GDP

2. The current account improved

Export volumes of goods and services from the region fell by 10% in 2020 with lower international demand and supply chains disrupted. Imports dropped by 12%. The current account balance improved from a deficit of 1.8% of GDP in 2019 to a half a percent of GDP deficit in 2020.[3] The fall in remittances early in the crisis caused real concern, but they bounced back, and low international interest rates kept interest payments in check despite rising debt.

3. Capital flows came back, reserves rose

March 2020 saw strong portfolio outflows from non-residents, but through 2020 many governments and large firms issued bonds abroad. Residents repatriated investments, and the IMF disbursed $5.2 billion through rapid finance instruments, arranged $45 billion of new or renewed flexible credit lines (Colombia drew down over $5 billion of its FCL), and Ecuador reached agreement on a new Extended Fund Facility of $6.5 billion. The IDB disbursed a record $16.5 billion and other official lenders increased flows. The upshot was a rise (yes a rise!) in reserves, and the IMF indicates there will be an additional $13 billion in reserves in 2020.

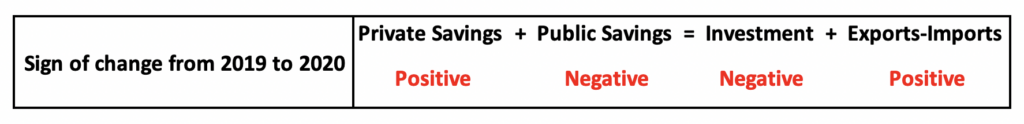

4. Investment fell, as did public savings, but private savings boomed

Another way to look at this is that investment fell relative to savings (investment fell by 1.4% of GDP and savings declined by just 0.1% of GDP). But fiscal deficits have ballooned from a 0.4% primary deficit in 2019 (4% overall) to a 7.3% primary deficit (10.8% overall) in 2020. So public savings have fallen sharply, but private savings increased by slightly more. See Figure 2 for a schematic version of the standard macroeconomic savings – investment balance. Consumption has fallen but has been smoothed by governments.

Figure 2: Macroeconomic Investment – Savings Balance

5. Debt is up

Fiscal deficits are spurring higher public debt ratios. IDB estimates suggest public debt will be 76% of GDP for the typical country in 2021, up from 57% in 2019 and will continue to rise before peaking, with the trajectory highly dependent on growth and future policies.[4] Firms’ leverage ratios also rose. They issued bonds abroad, but real investment has been limited. They built liquidity and are likely playing the carry trade – borrowing at low rates in dollars and earning a higher interest rate in local currency.[5]

6. Strong demand for liquidity

The money supply (base money) and bank deposits, such as checking and savings accounts, have risen. Central banks reduced interest rates and allowed banks to withdraw required reserves while governments drew down their deposits. Currency depreciations boosted the net worth of central banks that then found ways to provide liquidity to banks and governments.[6]

What are the implications of these developments? There are at least three potential risks that overhang recovery from the crisis: monetary, fiscal and financial.

- Monetary Overhang

Central Banks’ liquidity injections suggest risks in opposite directions. In a good scenario, if demand returns but supply constraints remain, inflation may rise. Perhaps this would be a good problem to have, at least if temporary. In the opposite direction, monetary policy may become ineffective. This may already have happened. Central banks extended liquidity, but some appears to have returned in the form of higher bank reserves held at central banks. Still, this is not an indication of a potential, persistent “liquidity trap”. After all, we are a collection of small and open economies. If external demand rises, investment should rise, public savings should increase and private savings fall. The real risks seem to be elsewhere. Some central banks have also amassed large amounts of short-term (sterilization) liabilities which could interact with roll-over risks for the fiscal authorities.[7] Monetary policy might become constrained by fiscal or financial dominance.[8] Central bank financing of fiscal deficits might be seen as a necessary evil. Financial sector woes might prompt calls for central banks to take on credit and not just liquidity risks.[9]

2. Fiscal Overhang

Most countries face an adjustment period in stabilizing rising public debt. But politics may constrain adjustment as hardship continues. Reforms to improve institutions could allow the process to be gradual and less painful.[10] Still high public and private debt may dampen growth. The alternative is to ignore the unpleasant arithmetic of sustainability leading to reduced access to credit and prompting roll-over problems. This could be the path to debt restructuring. Argentina, Barbados and Ecuador have already restructured, and new collective action clauses may make it less painful for others to follow. Monetary financing might be seen as a way to avoid restructuring, but this may lead to high and persistent inflation. A fast and mostly consensual restructuring would likely be less costly if financial sectors withstand the blow. The problem in the 1980s was not defaults per se. Rather, it was the lack of recognition of the losses, of kicking the can down the road, monetary financing, inflation and financial repression.

3. Financial sector overhang

Governments acted swiftly with loan deferral programs and accompanying regulatory forbearance.[11] These policies were understandable, but the longer they continue, the greater the uncertainty regarding the state of bank balance sheets and the greater the eventual losses. Large firms issued abroad but are not investing; they are staying liquid. Many banks have seen deposits rise and are more heavily invested in government paper. If corporates withdraw those deposits, given fiscal or financial concerns, funding issues could emerge. Bank balance sheets will deteriorate as loan deferral programs end. The management of financial sector risks will be critical to ensure a successful recovery.

Two key questions

As uncertainty is high, policy making is particularly challenging. How serious are the risks? This may depend critically on the answers to two questions:

First, how fast will we recover? Countries are trying to reopen their economies and grow, but the virus is still very much with us. In the US and elsewhere, reopening prompted cases to soar. As effective hospital capacity dwindled, lockdowns were imposed again from California to Italy, from South Africa to the United Kingdom. In Latin America and the Caribbean, hospital capacity is limited. New outbreaks and new lockdowns could dampen the IMF’s growth-rebound scenario. And the vaccine may only be widely administered in the second half of 2021. It will require skill to grow and keep the virus at bay until vaccines deliver enough immunity.[12]

Second, what will the post Covid-19 economy look like? The notion of a short, sharp crisis and a return to things as they were has faded. There will be winners and losers. There are opportunities here for adopting new technologies to improve productivity.[13] But more reallocation means more firms going under, and the region’s formal economies have limited flexibility. Reallocation has implications for labor markets, for the financial sector (more defaults) and for the fiscal outlook (greater support to workers and larger payouts on guarantees). We don’t know as yet how significant the reallocation effect will be. This will be an important area for future research.

[1] Figures in this blog come mostly from the IMF’s October World Economic Outlook. Figures for 2020 are estimates, although for ease of exposition, I often refer to them as facts.

[2] See Deep inequalities worsen Latin America and Caribbean vulnerabilities to crises

[3] The current account balance is the exports of goods and services plus remittance inflows plus interest earned on assets minus imports and interest payments to non-residents and minus any remittance outflows.

[4] See Avoiding a New Lost Decade for Latin America and the Caribbean

[5] The carry trade here refers to borrowing at low interest rates in dollars and investing in local currency at a higher rate.

[6] Still central banks in Latin America and the Caribbean have been much less aggressive than the US’s Federal Reserve or other Advanced Economy Central Banks and given the experience of previous crises have much greater restrictions on what they are allowed to do – see Sound Banks for Healthy Economies.

[7] Strong net government spending, capital inflows and liquidity provision to banks, as well as the rise in base money, promoted many central banks to sterilize (essentially mopping up some of the liquidity) by selling short- term paper or through short-term repurchase agreements.

[8] Fiscal dominance refers to the idea that interest rates should stay low or interest payments on high debt levels may be too high. Financial dominance refers to the idea that monetary policy becomes constrained to protect banks from becoming insolvent as higher rates may depress longer-term asset values relative to short-term liabilities.

[9] See Sound Banks for Healthy Economies.

[10] See Avoiding a New Lost Decade for Latin America and the Caribbean

[11] See Sound Banks for Healthy Economies.

[12] See Moving Beyond COVID-19: Vaccines and Other Policy Considerations in Latin America

[13] See From Structures to Services for an account of how new technologies may revolutionize infrastructure.

Leave a Reply