Few measures could be more important during the current Covid-19 pandemic than ensuring that the poor and vulnerable can eat, buy medicine and pay for other basic needs as they endure a months-long shutdown essential to protecting public health. But in Latin America where about half the population works in the informal economy, that is no easy feat. Many people in the informal economy depend on daily wages. Most of them, including those who are not especially poor, will have to shelter at home without earning an income, and may become poor again.

All this has brought the opportunity and effectiveness of government assistance to the fore as one of the defining issues of government policy during the Covid-19 pandemic. How well are governments targeting those most in need? How effective are existing government programs in replacing lost income? And what do their responses tell us about the structure of social protection programs in the region? Answering these questions and making the necessary adjustments are fundamental to ensuring that the poor and vulnerable, who will suffer the greatest share of the burden during the lockdown, are not inordinately harmed.

Recognizing the urgency of measures to deal with the pandemic, most countries have correctly relied on already existing social programs for vulnerable households. This has two advantages: It speeds up the targeting to those most in need, and it facilitates implementation. However, this approach has two drawbacks. First, existing conditional cash transfers have important coverage limitations. Even if their coverage were extended to 50%, some 5% to 37% of the poorest households would not receive any transfers, depending on the country.

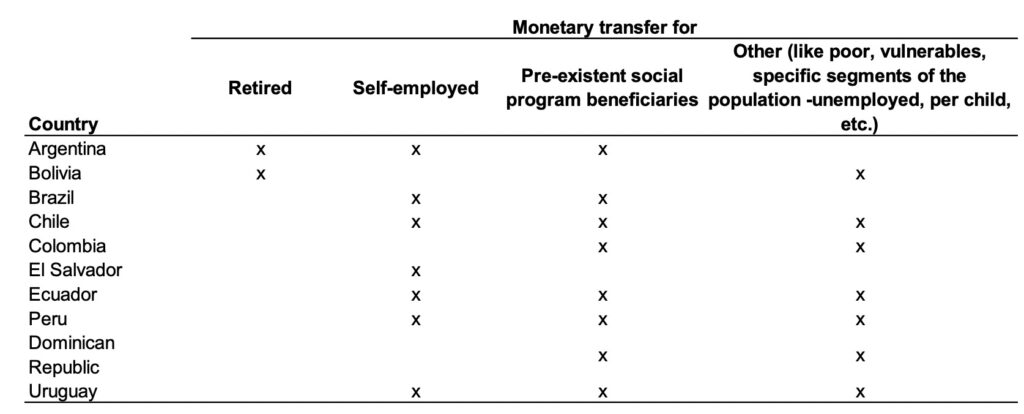

Second, existing programs are not designed well enough to provide insurance against transitory shocks. Many workers at risk of poverty, for example, are not typically beneficiaries of these programs. In particular, most informal workers, even those who are typically not poor, will be unable to earn an income from home and risk falling back into poverty if the lockdown is sustained over time. Thus, a second group of emergency transfers were rapidly introduced to include individuals at risk that may not have had access to existing programs, including the self-employed and the unemployed, among others. Table 1 describes which groups of the population had been selected to receive cash transfers related to Covid-19 in nine Latin American countries as of April 29.

Table 1. Cash Transfers for Different Populations by Country

Source: Authors using media and newspaper publications from each country, as well as information from the weekly publication by the COVID-19 Policy Measures Team of the IDB Group.

Note: The information in this analysis was last updated April 29, 2020. Note that some countries might have modified some of these policies afterwards.

Are these transfers enough to compensate for lost labor earnings? Most informal and poor households have no precautionary savings. Even if well-intended, transfers risk being insufficient if they do not compensate for a significant fraction of recipients’ already meager incomes. In order to assess whether transfers are large enough, we map eligibility for emergency Covid-19 transfers onto the last available household survey for each country (typically 2018). Then we adjust the labor income of the beneficiaries to 2020 prices and compare them with the amounts proposed by each program. We construct indicators of the programs’ potential coverage and their replacement rate across different segments of the population, which we divide in thirds depending on their labor income (also called income terciles). We concentrate here on coverage and generosity among the two poorest terciles.

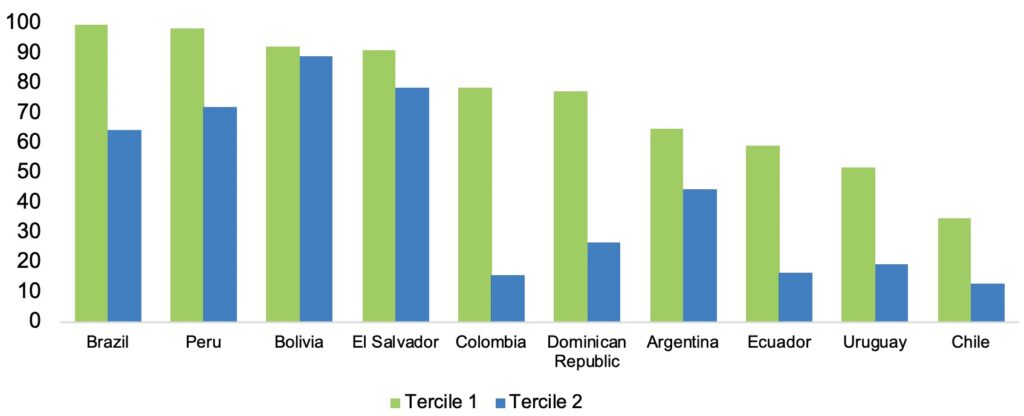

Figure 1 shows the percentage of households that are expected to receive the new transfers in the lowest third of the population (first tercile, green bar) and in the middle third (blue bar). The transfer in most countries should reach more than 75% of households in the first tercile. This is good news because the first tercile is almost exclusively composed of self-employed and informal workers. They constitute the people most likely to be affected by social distancing measures, as they tend to work in high proximity to other people and in jobs that are not suitable for teleworking. Note however that there is substantial variation across countries with cases like Brazil or Peru with coverage of 100% and 98% in the first tercile and cases like Uruguay or Chile with a coverage in the first tercile of 52% and 35%, respectively.

Figure 1. Percentage of Potential Beneficiary Households by Usual Monetary Labor Income Per Capita Tercile

Source: IDB staff calculations based on the mapping of emergency programs with respect to household characteristics. To evaluate these characteristics, we used IDB’s 2018 “Harmonized Household Surveys from Latin America and the Caribbean” for all countries, except Chile (2017), and adjusted household wages and income from those periods to 2020 prices.

Coverage is lower in the second tercile, suggesting a certain targeting of the emergency programs and the fact that many transfers build on pre-existing programs that target the poor. Informal and self-employed workers who typically have an income that takes them over the poverty line are more difficult to identify. This may be more problematic in some countries than in others. In Chile and Uruguay the coverage is low, but most households in the second tercile of the population are middle class and have some members in the formal sector, possibly with access to other programs and safety nets. More worrisome is the situation in Colombia, Dominican Republic, and Ecuador, with coverage rates below 30% in the second tercile, where the population is composed fundamentally of vulnerable households with no members in the formal sector.

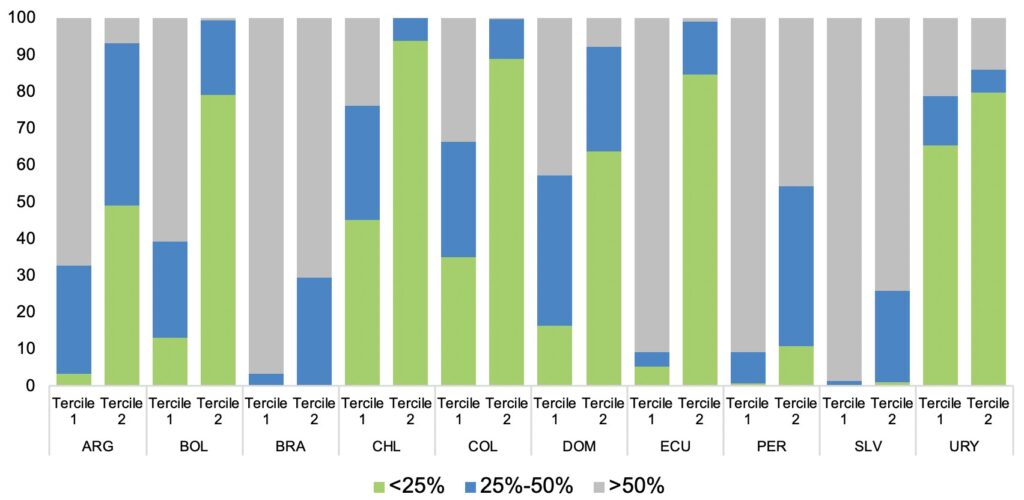

How generous are these transfers? Figure 2 shows the weight of the cash transfers as a proportion of the usual monthly monetary labor income (earned in 2018) for households in terciles 1 and 2. The replacement rate for the most vulnerable households (those in the first tercile) is generally high, but there are some exceptions. In Brazil, Peru, El Salvador, and to some extent Argentina and Bolivia, they cover more than 50% of the regular labor income. Dominican Republic and Ecuador are intermediate cases, with replacement rates below 25%. The replacement rate is lowest in Chile and Uruguay. In those two countries, around 50% or more of households in the first tercile will obtain less than 25% percent of their regular labor income through these transfers if their members cannot work during the lockdown.

With some noteworthy exceptions, the replacement rates are much lower among households in the second tercile. More than 60% of the beneficiaries in Brazil, El Salvador and Peru in this tercile are targeted to obtain transfers that exceed 50% of their regular labor earnings. At the other extreme of the distribution, more than two-thirds of the beneficiaries in the second tercile in Bolivia, Colombia, Chile, Uruguay, and Ecuador would obtain less than 25% of their previous and potentially foregone labor incomes.

Figure 2: Weight of Monetary Transfer in Usual Monthly Monetary Labor Income for Targeted Households in Terciles 1 and 2

Source: IDB staff calculations based on the mapping of emergency programs with respect to household characteristics and income. To evaluate these characteristics we used 2018 IDB’s “Harmonized Household Surveys from Latin America and the Caribbean” for all countries, except Chile (2017), and adjusted household wages and income from those periods to 2020 prices.

This analysis has limitations, of course. In some cases, the matching of the eligibility criteria in the different programs did not correspond directly with observable characteristics in the household surveys (e.g., some programs target pregnant women today, and we only observe household characteristics in 2018). Our analysis only allows us to observe the relationship between the proposed transfers in each program and pre-existing labor market income. Most workers in the first tercile of the population are informal with very limited capacity to telework, so it is not unreasonable to think that their labor income during the lockdown will evaporate. This does not automatically translate to zero income. Some households in this group might also be receiving non-monetary aids, such as food vouchers, in-kind donations, and help from family members. Similarly, some household members, in particular among the second tercile of the labor income distribution, may have maintained their ability to work, and/or could also be benefitting from other measures. Lastly, we evaluate the program as if all potential beneficiaries were to obtain the help.

These caveats notwithstanding, some broad conclusions seem clear. The proposed emergency measures do a good job in general of targeting the most vulnerable households: those in the first tercile of the labor income distribution. If programs are swiftly and efficiently implemented—a tall order in and of itself—proposed transfers may be able to sustain shelter-in-place measures for some time among these households. The situation in the second tercile of earnings, however, is more complicated. With the notable exceptions of Brazil and El Salvador, either low coverage or low replacement rates seem to call into question the effectiveness of the programs as they are currently formulated.

Governments have taken aggressive steps to save lives by ordering shelter-in-place regimes. They have swiftly and immediately implemented compensation programs to sustain incomes and facilitate stay-at-home orders. Those measures are all commendable. However, as argued in the 2020 Latin American and Caribbean Macroeconomic Report, the fiscal space continues to narrow in the region and is raising concerns about the long-term sustainability of these policies. Government responses also highlight structural problems across the region: the fragmented nature of social protection systems, which complicate the delivery of income support to informal workers who are not sufficiently poor to benefit from social assistance but lack other automatic stabilizers, such as unemployment insurance, that could alleviate the impact of temporary shocks.

The impact of the shortcomings of the social protection systems in the course of the current outbreak is still unknown and yet to be fully seen. But Latin America needs to seriously think about reforms that would provide a more effective and agile assistance to those falling through the cracks in times of crisis. Doing so would make the region more resilient.

[Editor’s note: The authors thank Eric Parrado, Andrew Powell and Norbert Schady for their valuable comments. Any errors are the authors’. The government’s measures on which this analysis is based changes rapidly. A version of the table and figures above with more up-to-date information as well as more details regarding the methodology can be found here.]

Leave a Reply