The Financial Times recently reported a sharp drop of lending from US banks to European countries.[1] But this is best characterized as part of a wider deglobalization process. As national authorities urge banks to lend to firms within their borders and provide liquidity and guarantees for them to do so, global players are becoming less global.

The syndicated loan market is an important source of finance for large firms, big infrastructure projects and even some governments around the world. Moreover, the trends in this market reflect those in cross-border credit generally. The total global syndicated loan market was about US$4.5 trillion in 2019. Banks lend in syndicates to tap global liquidity, to spread risk, earn fees and to manage their capital allocation.

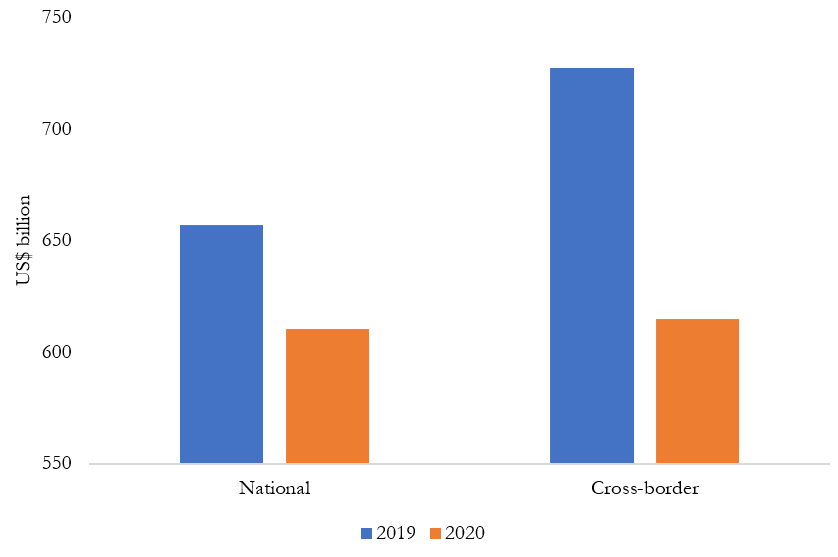

But in recent months, syndicated lending has declined significantly. Comparing the volume of syndicated loans extended from January to April of 2020 to that from January to April of 2019, the decline in cross-border lending has been much steeper than that within-borders. Cross border syndicated loans extended in the first four months of 2019 amounted to over US$728 billion whereas just US$615 billion was extended in the same period in 2020, a reduction of 15%. Lending within national borders fell by about 7%. Figure 1 compares syndicated lending within national borders to cross-border syndicated lending for the two periods.

Figure 1. National and Cross-border Syndicated Lending

January to April 2019 versus January to April 2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Refinitiv. Data is as of April 24th.

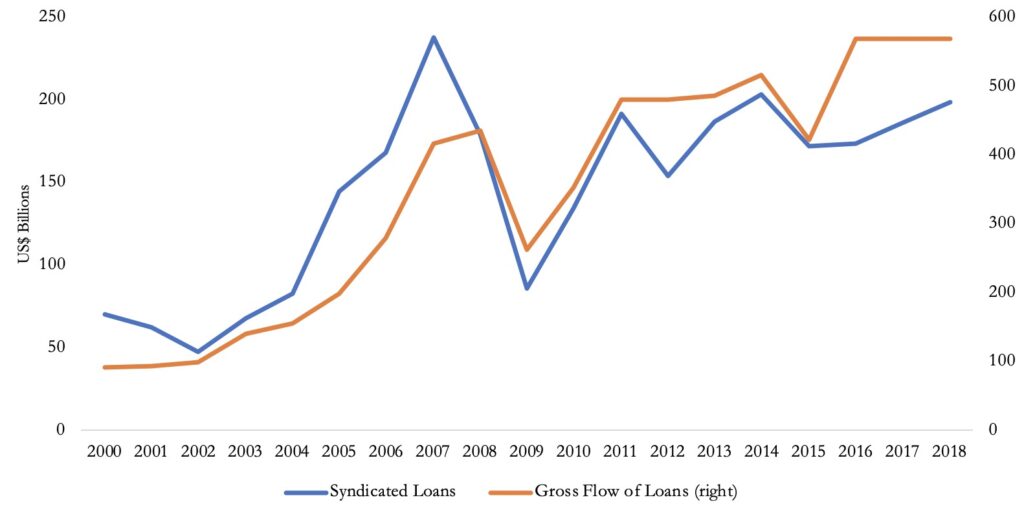

Cross-border syndicated lending is an important source of financing for emerging and developing economies. And as illustrated in Figure 2, the agreement of new syndicated lending is closely associated with the actual flow (disbursements) of commercial lending to developing countries. Both fell sharply during the global financial crisis but then recovered. New syndicated loans amounted to about US$200 billion to developing countries in 2018 but are now falling.[2] Moreover, developing countries have less ability to finance large fiscal programs in response to the Covid-19 crisis and their domestic financial systems tend to be smaller. For this reason, a deglobalization of banking may be particularly painful for these countries and add to the substantial redemptions that have occurred from equity and bond funds that invest in emerging markets. The 2020 Latin American and Caribbean Macroeconomic Report noted an outflow from bond funds equivalent to almost 4% of GDP for this region exceeding that experienced during the global financial crisis.[3]

Figure 2. Cross-border Syndicate Lending is an Important Element of Total Gross Credit Flows to Developing Countries

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Refinitiv and International Debt Statistics.

Note: Gross flow of loans are the gross flows (disbursements) of non-guaranteed (PNG) long-term commercial bank loans and public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) commercial bank loans from private banks and other financial institutions from World Bank data. Low and middle-income countries are included.

Large shocks to the cross-border syndicated loan market pose a serious threat, as they can propagate through the lender network, impacting the stability of the international financial system and further reducing credit flows to emerging economies.

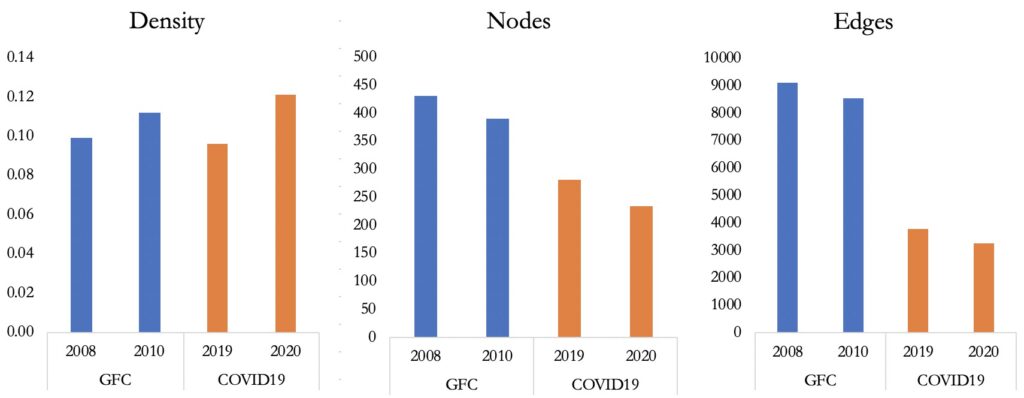

Network models from the academic literature suggest both resilience and fragility in the global financial system. In a forthcoming paper (Conesa, Lotti and Powell 2020), we find evidence of both. Focusing on cross-border syndicated lending to emerging and developing countries since 1993, we find that shocks propagate in the cross-border lending network through co-lending relationships, driven mostly by large players who occupy central positions in the network – typically the large global banks. At the same time, the network is resilient to shocks to banks that are located on its fringes and have limited co-lender relationships. The global financial crisis provoked changes in the network (Figure 3). During 2009 and 2010, it shrank with fewer banks (nodes, in network terminology) lending and fewer overall connections between them (known as edges in network parlance). But for those banks that did continue to lend, the density of the network increased (this density being a measure of the number of co-lender relations between the banks that actually remained as lenders). However, after 2010, as more banks started to lend again, density declined, that is, the network became less complete in terms of possible connections among banks. The main global banks became less global and new players entered, such as China’s official banks. We find results consistent with the idea that this reduction in density may have increased resilience to an average shock, in accordance with Acemoglu et al. (2015).

Figure 3. Density, Nodes and Edges in 2008-10 and 2019-20

Source: Author’s calculations based on Refinitiv.

Note: Data for 2019 and 2020 comprise the months between January and April for comparison purposes. Density measures how close the network is to complete, nodes are the number of lending banks, and edges are the co-lending relationships.

Yet, the Covid-19 crisis is no ordinary or average shock. It is already clear that it is having a significant impact. In keeping with the experience of the global financial crisis, the network is shrinking. While in January to April 2019, 281 financial institutions financed cross-border syndicated loans to developing and emerging countries for a total of US$79 billion, only 233 financed US$52 billion from January to April 2020. That is, the cross-border syndicated lending network at the beginning of 2020 had fewer players extending less financing. And as in the global financial crisis, the network that remains is more complete – the banks that are lending are entering into more relationships and seeking a greater diversification of risks. Density, in short, has risen. But this is also worrisome since according to the theory, and in line with our results, a denser network can be a vehicle for the propagation of large shocks. That is, while it seems that the effects of the crisis have not yet been fully revealed, there is a danger that this market will shrink further with greater impacts on the availability of credit for developing countries.

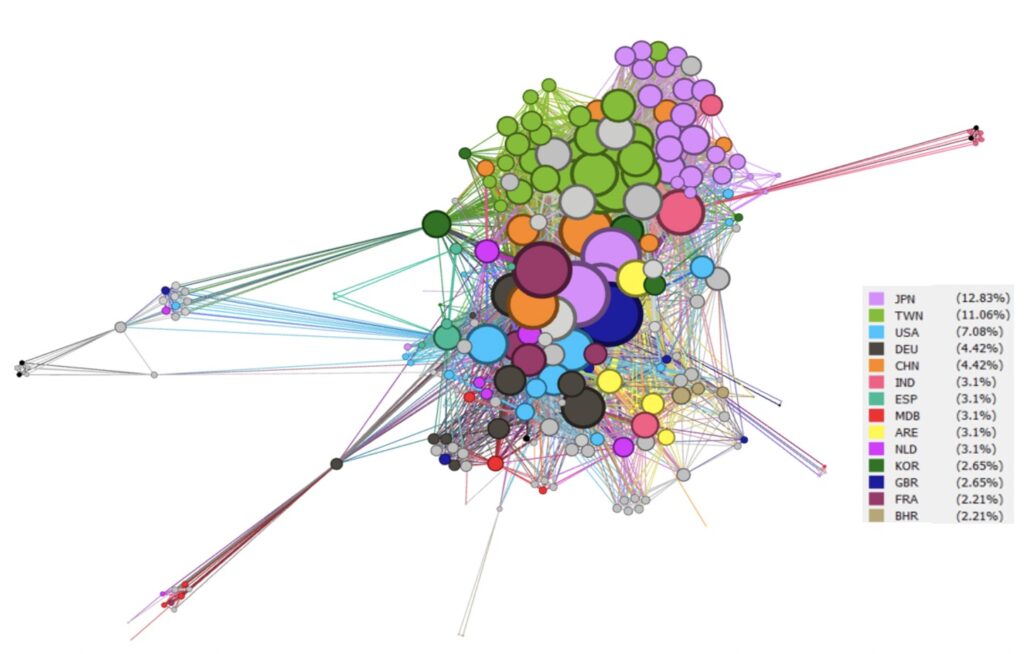

Figure 4 illustrates the lending network for the first four months of this year. Each bubble represents a bank, and the size of each bubble is in proportion to the number of co-lenders of that institution. The colors show the nationalities of the banks in question. Banks (bubbles) are placed close to each other when they syndicate loans together. As it is common for banks from the same country to form syndicates, bubbles of the same color tend to be close to each other. At the center of the network are the large global banks from the US, Europe and Japan. Taiwan is also important in the cross-border syndicated loan market, and some Chinese banks have now become central players. There are some clusters quite far away from the central mass. Typically, these consist of banks from some emerging countries that also participate in cross-border lending but that do not co-lend much with the central players.

Figure 4. Cross-Border Syndicate Lending to Developing Economies,

Network Visualization for January to April 2020

Notes: Authors’ calculations from Refinitiv.

Conesa, Lotti and Powell (2020) [4] find that large shocks that impact the central players propagate through the network and materially impact lending to developing countries. Banks lend less if their co-lenders lend less. Banks that are central have more co-lenders and so if they are impacted then naturally that will have a larger impact on total lending. From the standpoint of a borrowing country the reduction in financing is related to the proportion of loans received from banks that are central.

To identify which countries are at the highest risk of being hit by shock propagation, we look at how much of the volume borrowed through syndicated loans come from such banks. If central players focus on domestic lending and withdraw from the cross-border syndicated loan market, there may be greater “contagion,” reducing financing to developing countries further. We define central lenders as the top 10% of banks according to their centrality in the network.[5] In 2019, there were 726 cross-border syndicated loans to 79 developing economies. There was at least one central lender in 608 of those loans, co-lending with 14 other banks on average.

The countries most vulnerable to the reduction in credit from this market are those that obtain the most credit from these central players. In 2019, in Latin America and the Caribbean, these include Brazil (73% received from central lenders), Guyana (63% received from central lenders), Mexico (65%), Colombia (52%) and Panama (51%). Elsewhere in the developing world, countries such as Botswana, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kuwait, Liberia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Oman, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Togo all received more than 60% of syndicated loan financing from lenders who were central in the network.

Borrowers that tap international debt markets tend to be larger firms or banks. The syndicated loan market is a good bellwether for international credit flows. As in other crises, if larger firms are starved of this source of financing, they will tap domestic credit markets, potentially squeezing the availability of credit to smaller firms and households.

[1] See “US Banks Pull Back from Lending to European Companies” Financial Times April 24th 2020.

[2] This was more than 30% of all gross commercial credit flows to developing countries according to World Bank data.

[3] See also Corsetti & Marin (2020) and Davis (2020).

[4] Conesa, M., G. Lotti and A. Powell. 2020. “Resilience and Fragility in Global Banking.” Forthcoming. IDB.

[5] We employ something called “closeness centrality”, calculated as the reciprocal of the sum of the length of the shortest paths between the bank and all other banks in the network.

Leave a Reply