Education has long been promoted as a means for changing women’s position in society. Growing income, opportunity and exposure to more equal social norms, it is thought, should help protect women against abuse, not least by allowing them to choose better partners.

However, recent evidence shows that the role of education as a protective factor may be limited. Physical and sexual violence may be even more common among educated women. And educated women seem less likely to report it.

Stigma prevents reporting of abuses

If this seems counterintuitive, that may be partly because of the extreme difficulty of reporting on physical and sexual violence. Domestic abuse, after all, is largely invisible, happening behind closed doors. And for a variety of reasons, including the emotional, social and economic ties that bind intimate partners and the stigma attached to reporting abuse, women often keep silent.

Most research conducted on violence today relies on self-reported data, particularly Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), which rely on face-to-face interviews with direct questions about specific acts of violence. Due to their coverage (over 120 surveys in 61 developing countries) and the implementation of rigorous ethical and privacy protocols to guarantee the safety and wellbeing of survey participants, these surveys are considered the gold standard in the collection of data on intimate partner violence (IPV).

However, even the most rigorous protocols may be unable to give women the confidence they need to accurately report abuse. Women must, after all, still expose themselves to an interviewer who they do not know and admit to behavior, even if committed against them, that they find shameful and stigmatizing.

New ways to measure domestic violence

Research conducted in Peru by Jorge Agüero and I points to a possible way forward. We rely on an alternative survey method that provides full anonymity to women to get more accurate prevalence rates. Our results contradict traditional stereotypes and show that violence is highly prevalent among more educated women.

We surveyed about 1200 poor female microfinance clients around Lima and randomly divided them into a control and treatment group. In the control group, the questionnaire included direct, face-to-face, survey questions on several acts of physical and sexual IPV as in the traditional DHS surveys. But women were also given a list of 4 neutral statements (for example, have you every travelled abroad? have you ever lost a cellphone?) and asked to say how many of the statements were true.

The treatment group, meanwhile, did not get direct questions on physical or sexual violence, but was given the same list of four neutral questions as the control group with an additional question on a specific act of physical or sexual violence (for example, has your partner ever pulled your hair?) and asked how many of the statements were true.

Since randomization guarantees that the average number of statements that are true in the list of neutral statements is the same in both groups, the prevalence rate of a given act of physical or sexual violence is simply the difference between treatment and control group in the average number of statements that holds true. Indirect reporting in this way allowed us to infer aggregate prevalence rates without exposing women to the risks and negative feelings that direct reporting may entail.

The results were astounding. While overall there was no evidence of misreporting when direct methods were used, women with tertiary education, including technical school and university, were both more likely to have suffered abuse and less likely to report it. Fifty-one percent of more educated women, for example, had had their hair pulled by their partner. But only 17% of them reported that behavior in direct questioning, exposing a difference of around 34 percentage points between the real and reported prevalence rates. By contrast, 40% of less educated women suffered that type of abuse, with no statistically significant difference in prevalence rates across reporting methods.

Similarly, the indirect method reveals that women with higher education level were more prone to being punched (39%) or experience non-consensual sex acts (10.5%) than less educated ones (12.6% and 4%, respectively). These relationships between education and violence are completely inverted when we look at prevalence rates by direct methods.

A backlash against educated women may trigger violence

Why are more educated women experiencing greater levels of violence at home? It is not entirely clear. But a backlash effect may be at work. As women become empowered and their income level approaches or surpasses those of their partners, the struggle for influence and resources in the household may intensify. That can trigger violence, increasing its rate among educated women. At the same time, exposure to more equal social norms among the more educated may turn stigma into a heavier burden, leading to greater barriers for reporting the experience of violence truthfully.

One in three women in the world has experienced physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime, an estimate that does not count the many victims that remain invisible.

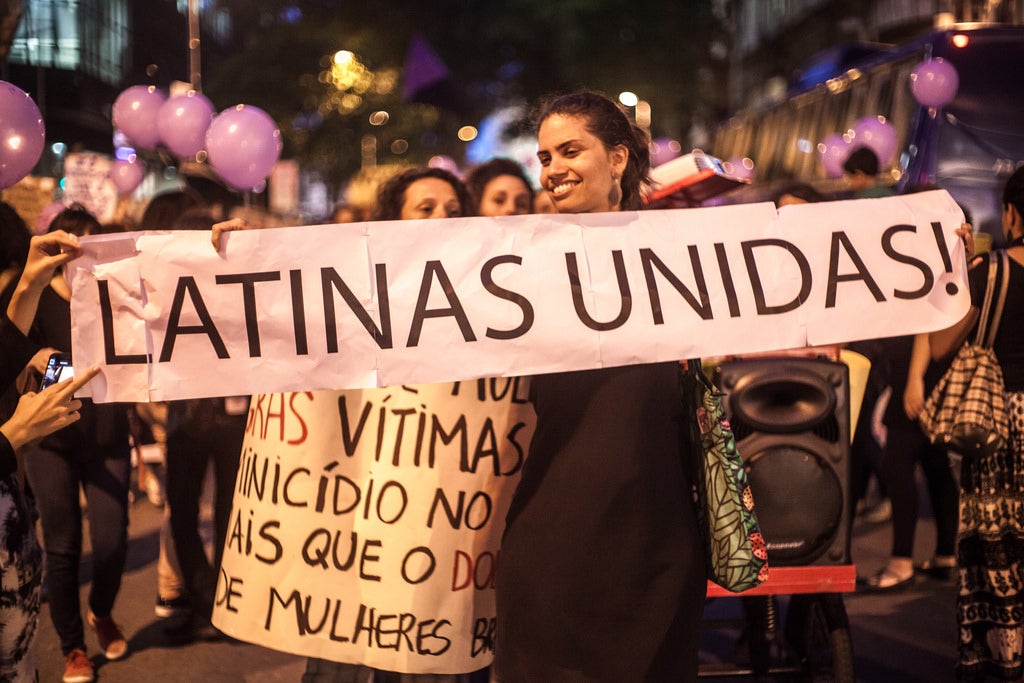

That, in turn, has contributed to the unleashing of a worldwide movement. After the body of a beaten and pregnant 14-year-old was found under her boyfriend’s house in 2015, for example, protests were organized around Argentina using the hashtag #NIUnaMenos. Tens of thousands of people took to the streets. A march organized in Peru by the movement the following year became the largest in the country’s history, with over half a million participants. And in the United States, denunciations of abuse ranging from movie stars like Angeline Jolie and Salma Hayeck to factory workers in Chicago, have led to a cultural upheaval with reforms promised from Hollywood to the media and the United States Congress.

But if the scourge of violence is to be truly combatted, it must be accurately measured so that interventions can precisely target the most vulnerable. Complementing traditional data collected with DHS surveys with measures derived from list experiments seems extremely promising to make violence visible among those who tend to keep it a secret.

Leave a Reply