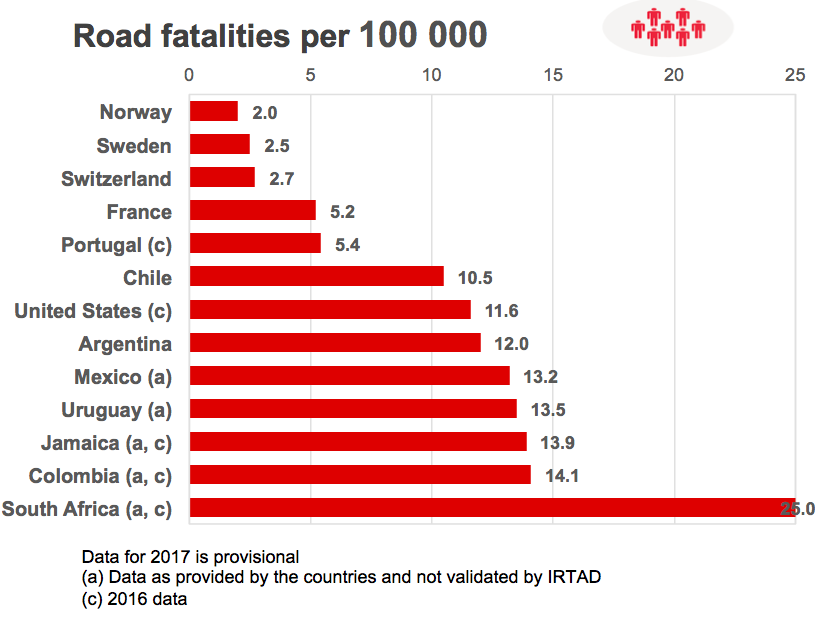

While plane crashes get the most media attention, we are much more likely to be injured in or by a car. And, in Latin America, the cost is very high. During 2017, car accidents claimed an average of 12 people per 100,000 inhabitants, five times the rate in Norway, more than double the rate in France, and even higher than that in the United States where road safety has been a perennial policy concern.

It is difficult to know what the causes of all these accidents are. What is clear is that a large percentage is due to human rather than mechanical failure. We are overconfident of our skills in driving and walking. We get easily distracted by our phones and disregard speed limits.

Legislation is not enough

Clearly something must be done and legislation is probably not enough. In Trinidad and Tobago, using a hand held device while driving can lead to up to three months in prison, and most, if not all countries, have some kind of restrictions on using cellphones while driving. Strong laws exist throughout the region against speeding. Still drivers text and speed, and pedestrians cross the road without looking.

At the rescue – at least for some problems – comes behavioral economics, which has shown to be an effective and efficient tool to reducing inconsistent and self-destructive behaviors in many contexts, including road safety. Solutions have taken diverse approaches. Nobel Laureate in Economics, Richard Thaler provides one of the most famous examples aimed at speeding. In his book Nudge, he explains how the city of Chicago painted horizontal stripes on the road before the Lake Shore’s sharp curves to create the illusion of speeding and encourage drivers to slow down.

Behavioral Economics to Reduce Speeding

In Philadelphia, Phoenix and Peoria, the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration painted 3D speed humps on roads to encourage drivers to ease up on the gas pedal. In the United Kingdom, the city of Norfolk planted 200 trees at decreasing distances along the side of the road, nudging drivers to slow down as they got closer to the village. And safety cameras, traffic feedback and Platewire, a platform where license plates of people who break laws and drive rudely are posted, have been tried in different parts of the world, as part of behaviorally-informed interventions to improve road safety.

Latin America provides one of the most colorful cases. In 1997, Bogotá Mayor Antanas Mockus, believing strongly in the power of theater to change behavior, hired 420 traffic mimes and placed them on street corners to make fun of traffic violators. In Mockus’s view, Colombians fear ridicule more than being fined, and that, perhaps, made public shaming a more effective policy than fines and other punishments.

Stopping pedestrians from endangering themselves by walking through red lights or crossing the street while texting have been subject to less behaviorally-inspired interventions, and, unfortunately their impact has hardly been evaluated. But a few stand out for their creativity. In 2014, for example Germany’s Smart company installed a “dancing traffic light” at an intersection in Lisbon, Portugal, which projected the animated images of pedestrians dancing in real time to music in a specially designed booth onto the traffic light itself. So effective were the images and the music in cutting the boredom of waiting for the traffic light that the company claimed it reduced red-light crossing at the sight by 81%.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SB_0vRnkeOk&t=18s

Fighting texting behavior to make roads safer

Changing texting behavior, for all its immense harm, also is yet to receive the treatment from behavioral economics that it deserves. But a recent study by the Perelman School of Medicine and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia suggests that too may be changing. The study, in the United States, where teenagers are more likely to die in accidents related to cellphone-use than any other age group, shows that more than 90% of kids would be willing to give up texting behavior while driving. Morover, more than half of the teenagers believed that having automatic phone locking while driving or providing a financial incentive would be effective ways of getting them to give up the habit. That suggested to researchers that the two strategies could be combined. A “Do Not Disturb While Driving” setting on smartphones would automatically block incoming messages when a car was moving. Teenagers, meanwhile, would download driving apps, recently on the market, that track driver behavior and offer financial incentives through car insurance programs.

The IDB is working together with local governments to develop behavioral initiatives that would expand some of these interventions into Latin America and the Caribbean. And it has established, along with I-Lab Paraguay, a competition for finding innovative solutions to both traffic and road safety problems, including through public-private partnerships. A meeting hosted by the IDB at the T-20 summit in Buenos Aires, Sept 17, will be looking at a broad range of behavioral interventions, including road safety.

The challenge — to make roads safer for all — is critical and urgent. The goal through behavioral economics is to accomplish it in the simplest ways possible.

Leave a Reply