As the importance of early childhood investments has become increasingly well understood, more and more interventions seek to improve parental engagement with their children. These interventions most often target mothers. But what about fathers? How much do they do for children in early childhood, and how effective have efforts been to help them do more? In a new review, we examine the role of fathers in early childhood around the world and the impact of interventions to engage them more fully.

For Father’s Day, we share five findings:

1. Less than three-quarters of children in low- and middle-income countries live with their fathers

Surveys of parenting practices in 69 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) show that only 72 percent of children live with their fathers! The number ranges across regions, from 61 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean to 96 percent in the Middle East and North Africa.

Fathers can be absent for many reasons, and their absence can affect children in multiple ways. The evidence on father absence is mixed: for example, migration of fathers has sometimes had negative effects on children’s health outcomes, but losing a father has often had little impact on children’s educational outcomes. These studies tend to overlook children’s mental health or overall well-being, which could obviously also be affected by the absence of a parent.

2. Fathers engage less in play and other activities with their children than mothers

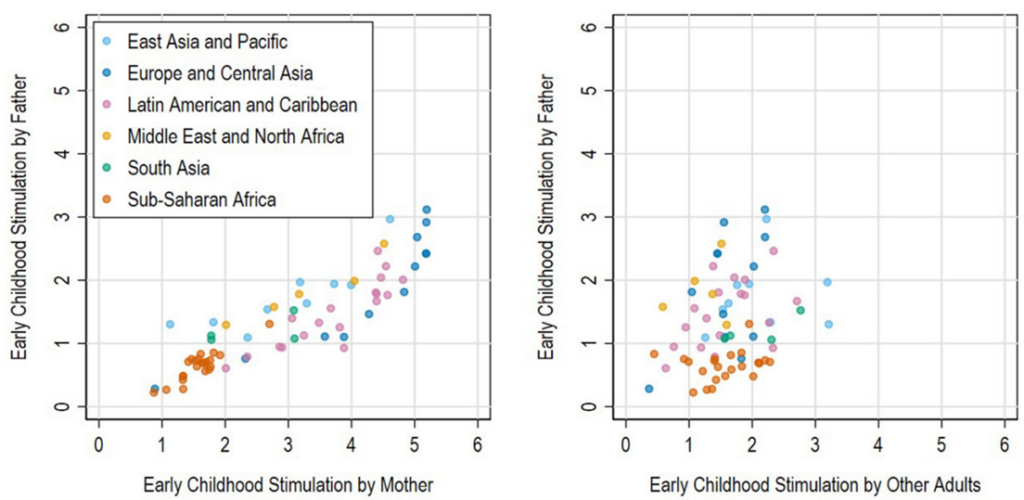

In almost all 69 countries fathers engage in play activities with their children—such as reading aloud, telling stories or playing—much less than mothers or even other adult members of the household (Figure 1). Out of six play activities asked about, mothers engage in 2.9 on average, and fathers engage in just 1.3. Other adult household members engage in 1.6.

This inequity between men and women reflects broader inequalities in care work, beyond that of children. Fathers also spend less time with children than mothers in high-income countries, although such time has risen dramatically in recent years in the US, for example.

Figure 1: Number of stimulation activities engaged by fathers, mothers, and others in the 72 hours previous to the survey in 69 low- and middle-income countries

3. Parenting programs can change fathers’ knowledge and behavior, but the evidence is mixed

Changing fathers’ knowledge seems possible, as shown by an examination of 22 evaluations of early childhood programs in LMICs. Early childhood health classes for fathers in one country boosted fathers’ knowledge. So did breastfeeding education for fathers in another. Yet, changing behaviors is more challenging: weekly group meetings for fathers and their partners to discuss parenting and gender equality reduced violence against mothers and children; but the same health classes that boosted fathers’ knowledge didn’t ultimately affect household behaviors. In one country, a digital parenting program (delivered through WhatsApp messages) actually reduced fathers’ interactions with their children!

In some (but not all) cases, programs that don’t specifically target fathers can improve their engagement with their children, suggesting that one way to help fathers’ to engage is to do so indirectly.

4. Engaging fathers is a challenge

Several projects have sought to invite fathers to participate with their partners. But take-up tends to be low: in one case, fathers attended just one out of 16 classes on average (as opposed to mothers, who attended 13). In another, men received invitations to early childhood health classes in some communities, and women received similar invitations in other communities. Attendance was nearly twenty percentage points higher in the women’s group communities.

5. We don’t know much about how programs affect fathers themselves

The vast majority of early childhood programs affect mothers, yet few measure impacts on mothers’ outcomes. Even fewer measure impacts on fathers. The ones that do often show impacts, such as changes in income and changes in stress. If we care about the overall returns to early childhood interventions, then understanding the ripple effects throughout the household is essential.

The Way Forward

Fathers are much less likely to be engaged in early childhood development activities than mothers. Efforts thus far have shown mixed success: take-up by fathers is often low, and when fathers do engage, the effects are not always positive.

Here are three suggestions for programs to consider going forward:

- Ask fathers what their constraints are and design programs to overcome those. Most interventions that target fathers use the same structure as existing programs for mothers. Yet fathers in LMICs identify specific challenges, such as less time at home, less knowledge about how to raise kids, and restrictive gender roles.

- Measure spillovers to fathers from training programs targeted to the primary caregiver. Several evaluations have documented positive spillovers onto fathers. Programs can measure those spillovers and explore nudges to help them happen more frequently.

- Close the know-do gap. The limited evidence we have on engaging fathers suggests that it’s easier to change their knowledge than their behaviors. Designing programs that ensure fathers have opportunities to practice what they learn may help bridge that gap.

Helping fathers to be full partners in their children’s early development will require creative program design to deliver programs that fathers are willing to participate in and that lead to more positive engagement with their children. It will also require ongoing evaluation to understand what works in this growing area.

Leave a Reply