Programs that provide care for children are good for women’s economic activity. More than 95 percent of studies in low—and middle-income countries show this, and studies in high-income countries show a similar pattern. For example, providing preschool in Argentina boosted mothers’ full-time employment. Providing daycare in Brazil boosted mothers’ work in the city of Sao Paulo and grandmothers’ work in Rio de Janeiro. They also boosted mothers’ income in Ecuador.

But what about children’s well-being? Do governments that expand access to childcare risk children’s development while expanding women’s economic opportunities? Our analysis suggests that the answer is no. Childcare is good for children and for parents.

A Study of the Impact of Childcare Services on Children’s Outcomes

For our recent study, “The Impacts of Childcare Interventions on Children’s Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries,” we looked for every study we could find that did two things: first, they evaluated the impact of a program that provided center-based care for children ages 0-5 in a low- or middle-income countries, and second, they measured the impact on children’s development. We include daycare for the youngest children and preschool and kindergarten for the older children. We found 70+ studies, including many from Latin America—Argentina, Brazil, Chile (which was still a middle-income country at the time of the studies), Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru—and around the world (e.g., China, Indonesia, and Turkey). These studies look at all kinds of children’s outcomes, including their learning outcomes, physical health, and socio-emotional well-being.

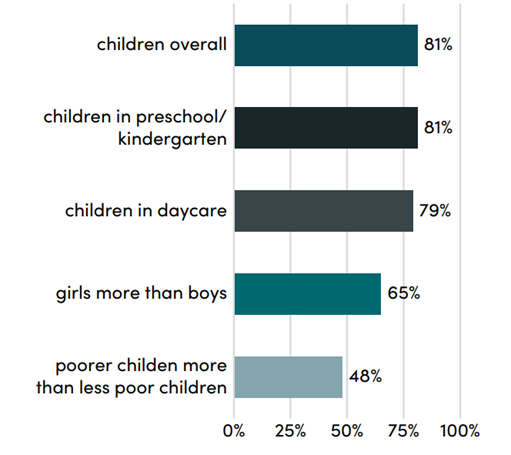

When you look at all these studies, you find that childcare tends to be good for children in these settings. Four out of five results show positive impacts on children overall (see figure below). We see these positive impacts with daycare expansions in Brazil, Colombia, and Nicaragua. Even when there are occasional negative results, they tend to be within interventions that also find mostly positive effects across all outcomes (as in another Colombia program or in Chile); in other words, more than nine out of ten studies find positive impacts on average. This trend towards positive effects is true for older children (in preschool or kindergarten) and younger children (in daycare). It’s true across all the classes of outcomes: children in childcare in these countries—at current levels of childcare quality—tend to have better learning outcomes, better physical health, and better socio-emotional well-being.

Figure: The proportion of results that show that childcare interventions benefitted…

We find that in two out of three studies, impacts are larger for girls than for boys. We do not see any consistent pattern of childcare differentially benefitting the poorest kids. In some studies, the poorest kids benefit the most (as was the case in preschools in Argentina), but in just as many others, either the less poor kids benefit most (in preschools in Cambodia) or there is no difference (in daycare centers in Nicaragua). Childcare may reduce inequality across children in some cases, but there’s no guarantee it will.

The Importance of Quality in Childcare Programs

Even though we see benefits at current levels of quality, that doesn’t mean that the quality of childcare doesn’t matter. Childcare quality encompasses many elements, from keeping kids safe to stimulating their development through regular, encouraging interactions with caregivers. Quality matters! In Peru, infants and toddlers in childcare centers with higher-quality interactions with caregivers had better development outcomes. There is even evidence that low-quality childcare can have adverse effects, but most of that evidence comes from high-income countries, often when childcare is serving higher-income households whose alternative to public childcare would be of very high quality.

These findings are a step forward. We examine 71 studies, whereas the last systematic review we found of childcare interventions on children’s outcomes in low- and middle-income countries had just six. But there is still much to learn. Our sample doesn’t represent very many studies in any one country. And nearly three-quarters of the studies in our sample focus on older children (ages 3-5), so we still have more to learn about the youngest children. We focus on positive and negative impacts because the range of outcomes and measures of those outcomes are so varied across studies, but future work can dig deeper into the size of these effects and—even more importantly—what characteristics of the childcare centers and of the beneficiary population lead to the biggest benefits.

But even as we continue to learn, the evidence we have suggests that childcare is a good bet for both women and their children.

Leave a Reply