Pension systems in the Caribbean countries have room for improvement. In our chapter, Pension Systems in the Caribbean: The Challenges Ahead, published in Economic Institutions for a Resilient Caribbean, we assess some pressing issues that will require attention to ensure the functionality and financial sustainability of pension systems in six Caribbean countries (The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago). Here are seven key elements to take into account when reforming pension systems.

- Pension system reforms must be tailored to each countries’ circumstances. Pension systems in Caribbean countries are based on a similar multi-pillar approach, which provides the elderly with a minimal level of protection via non-contributory social assistance, provides income security during retirement age through mandatory contributions in pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) programs, and promotes voluntary savings for retirement. Over the years, Caribbean countries have introduced reforms that provided temporary relief to the financial sustainability of their pension schemes (IMF 2016). However, authorities need to continually assess the viability of the system. Population aging, insufficient population coverage, high labor informality, low benefits, increasing deficits in pension schemes, high administrative costs for social protection programs, and discrepancies between civil servant pensions and those of the rest of the population in the Caribbean are the main challenges. Based on these challenges, we provide some insights to consider when designing pension reforms in Caribbean countries.

- Population aging increases the urgency of addressing the financial sustainability of pension systems. The long-term sustainability of pension schemes comes into question as the population ages and the working population increasingly carries a heavier burden to finance the pensions of an expanding group of retirees. Currently, most Caribbean countries, except Barbados, have relatively younger populations compared to Latin American and OECD countries. However, due to demographic changes, adults aged 65 and over will constitute 20 percent of the population of the six Caribbean countries analyzed by 2050, an increase of around 11 percentage points from the current share. Moreover, the ratio of population over 65 years old to population between 15 and 64 years old is expected to double by 2040 in the Caribbean countries, a faster aging process compared to Latin America and OECD countries. These unprecedented demographic trends represent an important challenge.

- The benefits of pension systems in the Caribbean vary across the region. According to recent pension benefits simulations, insured retirees in the Caribbean would receive retirement pension benefits relative to earnings at working age (or replacement rate) in a range that goes from 38.8 percent to 68.6 percent. These simulations assume that the average insured would contribute to the system throughout all working age years (100 percent contribution density). However, this is not the case for countries that face high levels of informality.

- Low compliance and labor informality jeopardizes the provision of social protection to the most vulnerable. Switching from the formal to the informal sector several times during workers’ careers reduces their contributions to social insurance programs in the formal system, thus increasing their likelihood of not qualifying for an old-age pension. Caribbean countries with relatively high levels of informality have a coverage rate in social insurance pension programs in the range of 50 percent of the eligible population. Looking forward, policies to increase the number of contributors would not only augment the revenue streams in the PAYGO programs but would also benefit the insured by increasing their likelihood to access a pension.

- The administrative costs of social protection programs in Caribbean countries are high, ranging from 4.5 to 17.6 percent of contribution income and from 0.2 to 0.4 percent of its GDP. Overall, Jamaica and The Bahamas have the lowest pension system expenses among the Caribbean countries (1.98 and 3.21 percent of GDP, respectively). In Suriname, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago, total expenses vary between 3.9 and 6 percent of GDP. Barbados has the highest pension expenses, with a point estimate of 8.86 percent of GDP, and a range from 7.5 to 13.2 percent of GDP. Given the expected increases in pension costs in the coming years, reducing administrative expenses and using these resources to finance pension obligations could be considered.

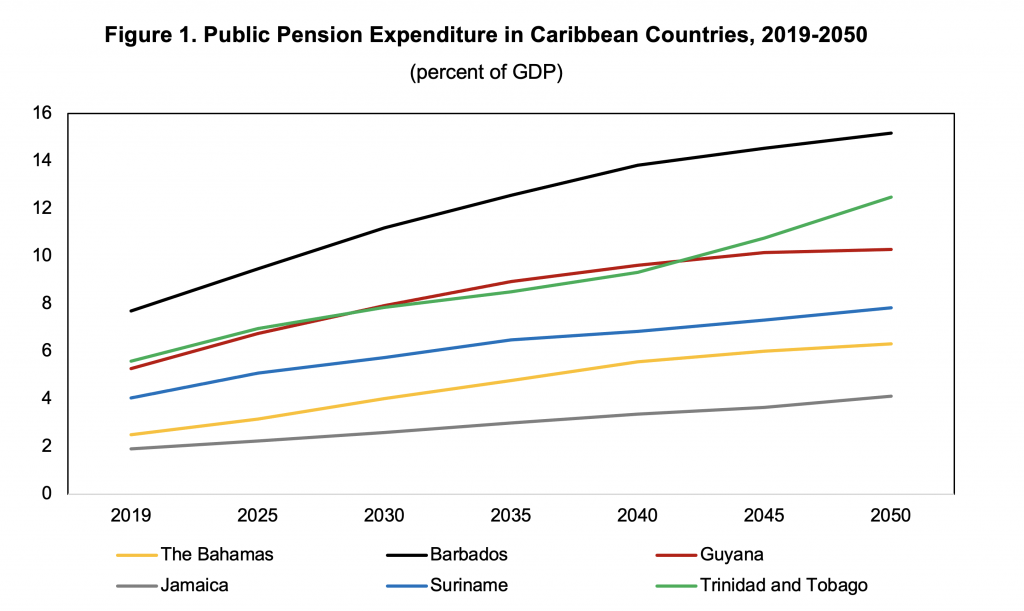

- All Caribbean countries are expected to experience increases in public pension expenditures in the coming decades. Countries that have the highest proportion of senior citizens in their population (Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago) are expected to have the highest public pension expenditures (i.e., costs associated with social assistance, social insurance, and civil servants’ programs) in 2050. Considering the population forecasts and assuming there is no reform in the Caribbean pension systems, public pension expenditures could fluctuate between 2.6 and 15.2 percent of GDP by 2050 (Figure 1). Barbados (15.2 percent) is expected to have the highest public pension spending as a percentage of GDP, followed by Trinidad and Tobago (12.5 percent), Guyana (10.3 percent), Suriname (7.8 percent), The Bahamas (6.3 percent), and Jamaica (4.1 percent).

- Increases in pension expenses could erode the governments’ ability to provide other relevant services to the population. Assuming that social expenditures in Caribbean countries remain constant as a percentage of GDP, the increasing public pension expenditures would result in significant declines—from 9.08 percentage points of GDP in 2018 to 5.02 percentage points in 2050 on average for the Caribbean countries—in the amounts remaining for other public spending components of social expenditure, including health care and support for improved living conditions of the poor and other vulnerable groups, which could also face pressing needs because of an aging population.

Given this context, what can the Caribbean countries do to reverse this situation and prepare for future challenges? To tackle the challenges of financial sustainability and adequacy of benefits, authorities should review the design of their pension schemes, such as the eligibility criteria, administrative costs and contribution rates. Some Caribbean countries have already taken steps in this direction. This is particularly the case of Barbados, that has recently increased the age of retirement of their pension schemes as well as their contributory rates. Today, the contributory rates in Barbados are as high as those of the OECD countries, which have higher old-age dependency ratios. In countries with high levels of informality, structural changes in labor market dynamics could increase the coverage of pension systems. In these countries, increasing the coverage and benefits of social assistance programs could help guarantee a higher quality of life for the elderly, especially those without access to social insurance. However, those efforts are beyond the scope of a potential pension reform.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected the Caribbean, it remains important to focus on needed long-term structural reforms. The pandemic has not only taken away lives but has also devastated livelihoods. In the aftermath of the current crisis, Caribbean countries need to refocus their attention to their pre-COVID institutional arrangements and prioritize the relevance and sustainability of such commitments. Pension reform should be highly ranked on the reform agenda. The window of opportunity for appropriate and comprehensive reform is closing and needed adjustments to Caribbean pension schemes should be tackled as early as possible.

Leave a Reply