The Pandemic has produced the deepest economic shock on record for most countries in the Caribbean region, and the pace and degree to which countries recover will depend crucially on policy choices and actions of governments in the near term. The Inter-American Development Bank Caribbean Department’s most recent Quarterly Bulletin focuses on the health, economic, and policy implications of the shock, as well as options available to mitigate its impacts. This edition considers the recent uptick in cases across countries, and builds on work discussed in previous editions, while taking a deeper look at: the spread of the virus and what issues should be considered when reopening borders and economies; a review of stimulus and support measures undertaken by countries across the world, aimed at identifying key objectives and best practices; and, a focus on public infrastructure investment in the region and how this can help support economies through the crisis, while also setting the stage for faster post-COVID development. Highlights from the publication are outlined below.

A Pandemic Surge

Except for Barbados, the region experienced a new surge of COVID-19 cases toward the end of the summer.[1] Several factors contributed to this unfortunate situation: a rise in imported cases as borders opened, an increase in community transmission as domestic social distancing measures were eased, and elections with in-person voting in three countries—Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and Jamaica.

The surge in new cases further complicates the prospects for recovery as the recession grinds on. Health and sanitary restrictions and social distancing measures are being re-imposed or strengthened in some countries, as are border restrictions. Even as they are necessary to contain the pandemic, the measures have an inevitable impact on prospects for an economic recovery. One positive sign is that in recent weeks, the rate of new identified infections has slowed in several countries, bringing some relief.

Evolving Policy Responses

In addition to creating new instruments to address the crisis, governments have drawn on existing programs to ramp up social assistance. For example, The Bahamas and Barbados entered the crisis with a well-established unemployment insurance mechanism to provide a social and economic “automatic stabilizer.” Jamaica increased the scope of its conditional cash transfer program (the Program of Advancement through Health and Education). Governments across the region also created new programs to help businesses in hard-hit sectors—especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)—, survive the ongoing recession. The size of overall fiscal packages varies from about 1½ to 11 percent of GDP, substantially smaller than in some of the largest economies in the world, but broadly in line with the policy packages in middle-income countries.

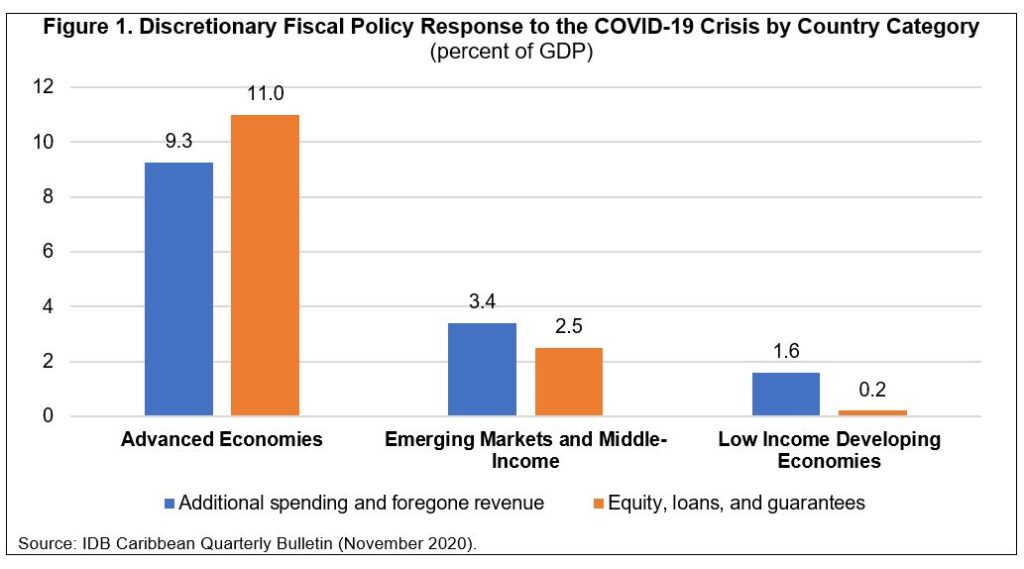

Common policy interventions can be broken down into several categories: direct expenditures to combat the health crisis, expenditures or tax reductions benefiting households and firms; accelerated spending or deferred revenue; and, liquidity support via equity or loans to firms or guarantees. Advanced economies generally have better access to finance, so it is not surprising that they have responded to the crisis with larger discretionary fiscal policy responses as a share of GDP (Figure 1).

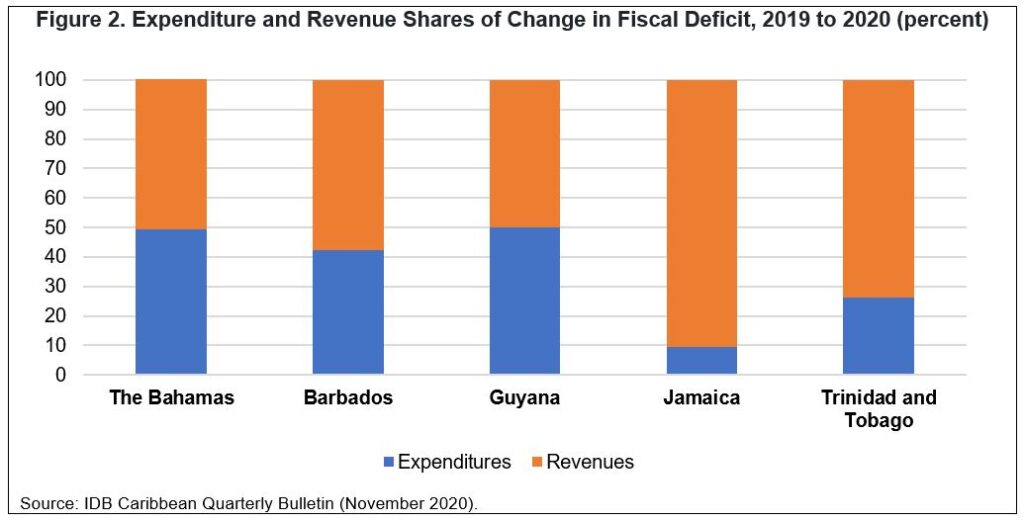

Governments around the world are allowing fiscal deficits to grow in response to the economic and health shock. In addition to the expenditure stimulus measures outlined above, governments have let the decline in revenues associated with the recession be passed through to deficits. In fact, Figure 2 below shows that revenue declines were responsible for 42 to over 90 percent of the change in deficits between 2019 and 2020.

Interventions focused on immediate health needs, as well as vulnerable households and corporates have been prudent, but the next phase should include an acceleration of infrastructure investment. Given their initial conditions, Caribbean countries stand to benefit tremendously from well-designed and appropriately prioritized investment. By increasing an economy’s productive capacity—for example, better roads or airports facilitate the transport of goods and services to market, improved water and power infrastructure enables industry to operate at lower costs, etc.—public investment increases the marginal product of capital and labor. Over time, that in turn drives higher levels of private investment, incomes, and consumption. Importantly, both economic theory and empirical evidence suggest that countries with relatively less public capital, or where the stock of capital is in need of improvement, stand to benefit most.

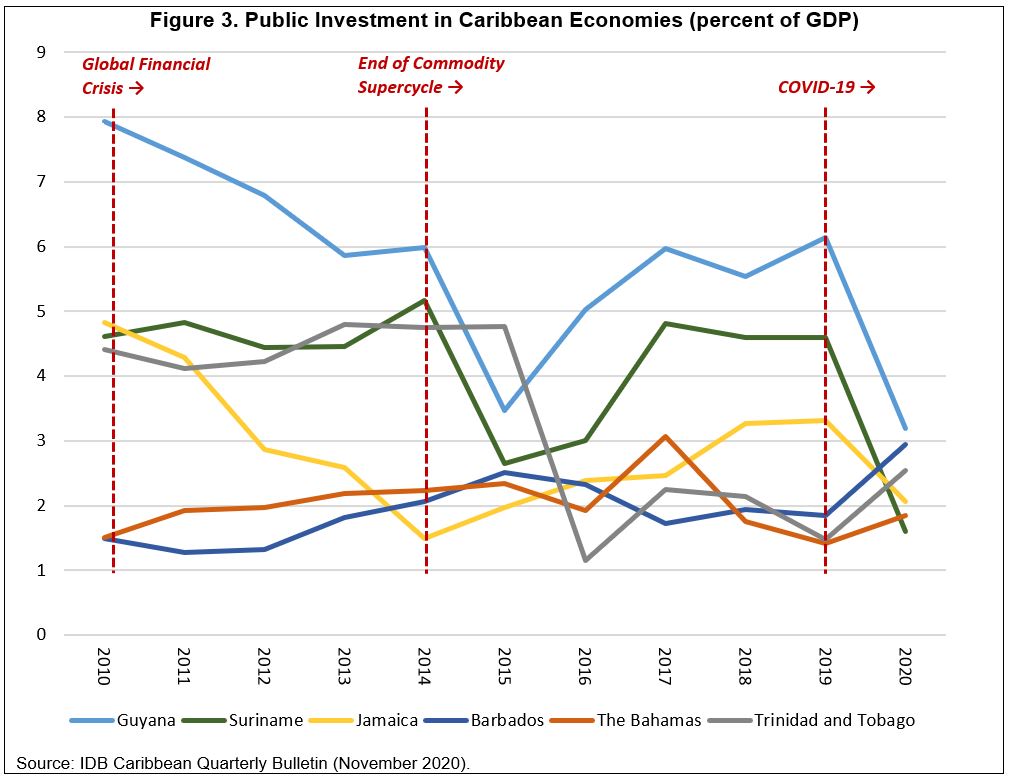

In this context, the past decade has seen declines in public investment levels across Caribbean economies. Beginning in 2014, and coinciding with large declines in global commodity prices, levels of public investment in commodity exporters Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago—measured in terms of the general government’s net acquisition of nonfinancial assets relative to GDP—saw single year contractions of over -40 percent, -50 percent, and -75 percent, respectively (Figure 3). For The Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica, whose economies rely heavily on the tourism sector, the global financial crisis and related shocks to external demand precipitated appreciable decelerations in public investment. In Jamaica, for example, these annual outlays fell by over 60 percent from 2010 to 2014.

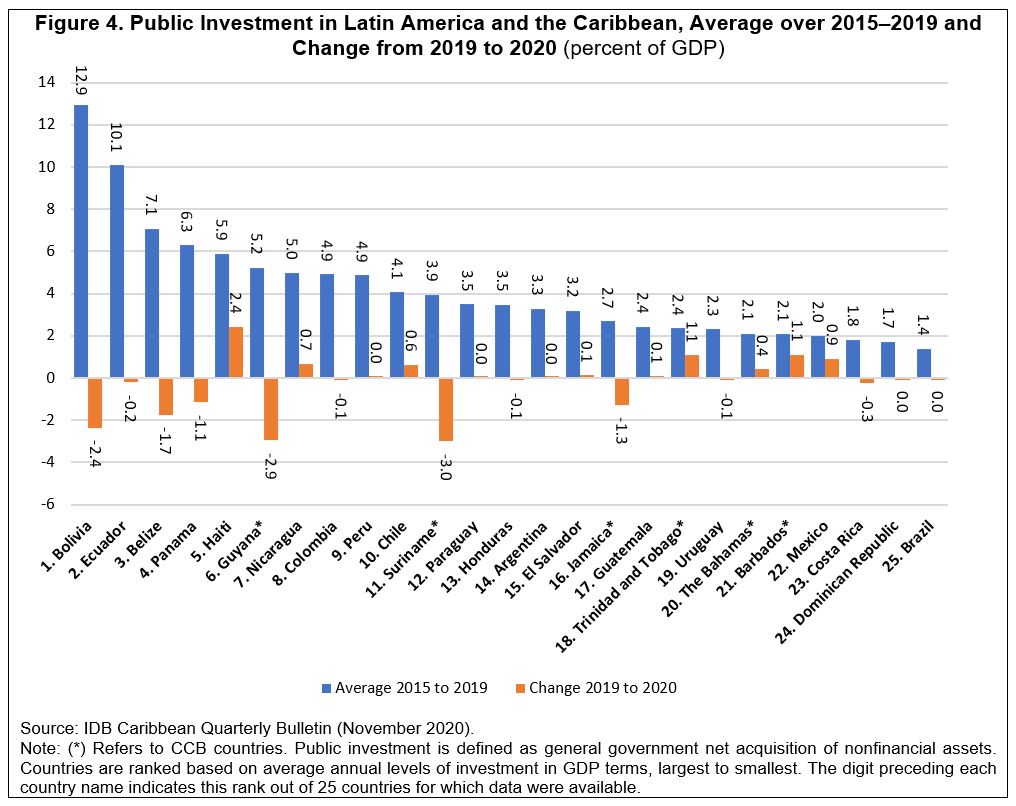

Against this backdrop of recent shocks to public investment across countries in the region, the pandemic has created further challenges. When comparing public investment levels (relative to GDP) across LAC countries over the past five years, one sees a wide range of outcomes. Guyana ranked 6th out of 25 countries across the region for which comparable data were available, but other countries like Barbados, The Bahamas, and Jamaica ranked in the bottom half of the distribution (Figure 4). Importantly, the COVID-19 crisis forced many countries throughout the Americas to reprioritize budgetary outlays, and in some cases to compress investment spending relative to previous years and pre-crisis expectations. Of the 11 countries that are expected to see public investment levels contract between 2019 and 2020, the two largest compressions will take place in Caribbean economies—Guyana and Suriname, each with a fall of about -3 percentage points of GDP.

Looking forward, the reprioritization of public investment should be a central objective throughout the Caribbean. It will be important to ensure that related outlays are appropriate in terms of the prioritization of critical needs, and that projects are undertaken in a cost-effective and efficient manner. Similarly, making sure that government financing for such projects is undertaken in a way that minimizes risks to the public balance sheet will be important to ensure that the benefits of public investment outweigh the costs.

Country Specific Chapters

The report also includes country-specific sections focused on the implications for of the crisis for economic performance, as well as policy measures that have been announced and undertaken by governments in The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, as well as the six sovereign member states of the OECS. In the report, our country economists review policy options that remain available, and provide advice regarding some of the most promising, within the context of constraints facing policymakers.

[1] The Caribbean region refers to the six member countries of the Inter-American Development Bank’s Caribbean Country Department: The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Leave a Reply