Economists are a depressing bunch. Our role is to anticipate and assess risks, which one could argue makes us too despondent. And if you’re lucky enough to get an optimistic outlook from one of us, it will follow by something like ‘on the other hand, the risks are skewed to the downside’. That said, we just published the December 2018 Caribbean Regional Quarterly Bulletin, which fits into the restrained optimism of our field.

While the economic trends in the Caribbean in 2018 are generally encouraging, divergence in the development of the various countries has increased, as have risks to the outlook. According to recent estimates, average growth for the six Caribbean countries that constitute the IDB’s Caribbean Department have increased from 0.6 percent in 2017 to 1.6 percent in 2018. In addition, the IMF estimates that these economies could experience 1.9 percent growth in 2019. However, trends in the different countries vary, as there is a considerable difference in the current and expected macroeconomic performance for 2019 between tourism-dependent countries (The Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica) and commodity-producing countries (Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago). Additionally, Barbados and Suriname face country-specific economic challenges.

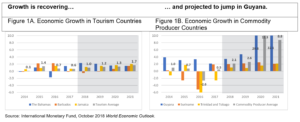

The performance of tourism-dependent Caribbean countries continues to improve (Figure 1A): The Bahamas is recovering from the effects of hurricanes in 2016 and 2017 that led to higher public spending and interruptions in the flow of revenue. For 2018, expectations are for a recovery of growth (2.3 percent). While Jamaica should see a small acceleration in growth from its recent low levels, Barbados’ economic performance has been affected by the uncertainty affecting its economic situation in the first half of 2018.

Commodity-producing nations are turning the corner (Figure 1B). These countries benefit from increases in the prices of raw materials. In 2018, economic growth of these countries is estimated to be 2.1 percent, up from an average of 0.5 percent in 2017 and growth is expected to reach 2.6 percent in 2019. For its part, Guyana is already beginning to feel the effects of oil production that will begin in 2020 and that is expected to lead to growth rates of more than 20 percent in 2020 and 2021. The projections for Trinidad and Tobago are for a slight economic acceleration (growth of 0.9 percent in 2019 and 1.6 percent in 2020), while Suriname’s growth rate is projected to stabilize at around 2 percent.

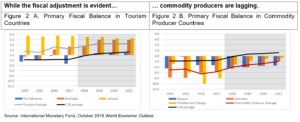

Fiscal adjustment remains high on the policy agenda in the Caribbean. The better economic outlook in The Bahamas should be reflected in a substantial improvement in its fiscal effort (a primary fiscal balance of 0.1 percent of GDP compared to -3.4 percent in 2017) that will lead to a stabilization of debt as a percentage of GDP below 55 percent. Jamaica continues to implement fiscal reforms and has benefited from a reduction in its debt as a percentage of GDP (97.4 percent at the end of 2018 compared to 145 percent in 2012). In Barbados, fiscal vulnerabilities had accentuated, prompting the new government to sign a 48-month agreement with the IMF. As a result of fiscal consolidation measures that have already been started, debt-to-GDP is projected to fall quickly.

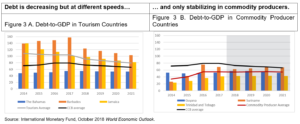

Despite the improvements in the growth rates of commodity producers, the fiscal efforts of these countries remain insufficient. The average primary balance improved only slightly from -5.7 percent of GDP in 2017 to -4 percent in 2018, and public debt remains high compared to levels prior to the global financial crisis (average of 54.1 percent of GDP in 2018 compared to 32 percent in 2007). The situation is more critical in Suriname, which saw its debt as a percentage of GDP almost triple between 2014 (26.3 percent) and 2016 (75.8 percent). While Guyana’s oil production will completely alter its fiscal and debt trajectory after 2020, the recoveries in Trinidad and Tobago and Suriname are expected to be accompanied by a greater fiscal effort that should help stabilizing debt around current levels (43 and 63 percent of GDP).

Several risks to the outlook persist. Apart from Guyana, all countries are pursuing fiscal adjustments that are needed to control debt levels, reduce interest costs, and keep investor sentiment positive. While average debt is 72.9 percent of GDP in 2018, it varies widely between the different countries: Suriname (62.5 percent), Jamaica (97.3 percent), and Barbados (123.6 percent) (Figure 3A and 3B). Moreover, debt levels are above the debt sustainability levels of small countries worldwide with open and undiversified economies (approximately 60 percent of GDP). Other policy reforms that are needed include: improving the business climate, enhancing access to finance, and providing greater support for infrastructure investment (See the September 2018 Quarterly Bulletin for an overview of development challenges). The Caribbean countries are also susceptible to external economic conditions and shocks. Climate change and natural disasters exacerbate the region’s macroeconomic challenges. The estimated cost of the impact of hurricanes and floods in the region is approximately 2 percent of GDP per year.

Taken together, the outlook remains subdued but positive. The world economy is expected to continue its expansion in 2019, but forecasts are slightly less optimistic going forward. For example, in October 2018, the IMF has reduced the overall growth predictions to 3.7 percent for 2018 and 2019, which is 0.2 percentage points less than its April 2018 estimates. This more cautious tone reflects increasing downside risks and weaker-than-expected performance in some countries together with a possible plateau of growth. For the Caribbean, projections are for slow but steady progress. While several countries still have income per capita below 2007 levels, economic performance has in general improved and the outlook remains positive.

The strengthening of commodity prices should benefit the commodity-producing countries. This is especially the case for Guyana, where imminent oil and gas production is raising expectations of a strong push to GDP.

Tourism-dependent countries need to continue to implement the reform agenda, especially regarding fiscal affairs and debt. The outlook for these countries will depend on their ability to continue to lower debt-to-GDP ratios and on favorable external conditions. In addition, all countries should pursue growth-friendly reforms and ramp up infrastructure investments, which have suffered since 2008.

Juan Pedro Schmid is a Lead Economist in the Caribbean Country Department of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Since joining the IDB, Juan Pedro has worked in different capacities, including as a country economist for Jamaica and for Barbados, and as regional macroeconomist. His work has covered a broad range of areas, including macroeconomic monitoring, preparation of country strategies, lending operations, coordination of departmental macroeconomic work, and programming and research on a broad range of topics. Before joining the IDB, he worked for three years as an Economist at the World Bank’s Economic Policy and Debt Department on debt relief operations, technical assistance missions, and advisory services across different regions, including Africa, Asia, and Oceania. He holds a M.A. from the University of Zurich and a Ph.D. from the Federal Institute of Technology, both in economics.

Juan Pedro Schmid is a Lead Economist in the Caribbean Country Department of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Since joining the IDB, Juan Pedro has worked in different capacities, including as a country economist for Jamaica and for Barbados, and as regional macroeconomist. His work has covered a broad range of areas, including macroeconomic monitoring, preparation of country strategies, lending operations, coordination of departmental macroeconomic work, and programming and research on a broad range of topics. Before joining the IDB, he worked for three years as an Economist at the World Bank’s Economic Policy and Debt Department on debt relief operations, technical assistance missions, and advisory services across different regions, including Africa, Asia, and Oceania. He holds a M.A. from the University of Zurich and a Ph.D. from the Federal Institute of Technology, both in economics.

Leave a Reply